What the nephew was to inherit

On the 20th day of July in the year 1861, a New Zealander by the name of Charles Trick executed his last will and testament.

In many ways, there’s really nothing unusual about the document.

It’s got the usual language about “by the Grace of God” the testator “being of Sound mind.”

It’s got the usual language about “by the Grace of God” the testator “being of Sound mind.”

It’s got the usual two witnesses: Carpenter Arthur and John G. Arthur, both of Pit Street in Auckland.

It’s got the usual bequests, to a whole bunch of nephews and 10 pounds to his mother.

And it’s got the key bequest — the bulk of the estate was to one particular nephew who lived there in Auckland and who, it appears, was named for his uncle: Charles Trick Hosking, who was also named as executor.

It seemed for a while like the only thing that was a bit unusual was a codicil to the will, added on the 23rd of August 1862: it added another 50 pounds to the 50 pounds already being left to one of the nephews, Richard Cory Hosking, brother of the executor and main heir.

And otherwise it was all pretty routine.

Except, while reading through the will, The Legal Genealogist came smack dab up against a total “huh?” moment.

Because there is a term in the will that, I confess, I hadn’t come across before.

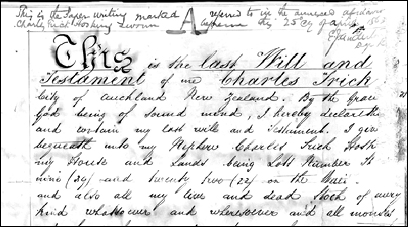

The main section of the will reads:

I give and bequeath unto my Nephew Charles Trick Hosk(ing) my House and Lands being Lots Number Th(irty) nine (39) and twenty two (22) on the (blotted) and also all of my live and dead Stock of every kind whatsoever and wheresoever …1

House. Check.

Lands. Check.

Live stock. Check.

Dead stock. Huh?

I confess to all kinds of mental images of dead animals littering up a farm pasture.

Fortunately, the reality is much more prosaic.

You won’t find it in the law dictionaries — neither Black nor Bouvier defines the term.2

Nope. This one has to be looked up in the plain ordinary every day dictionaries.

Where, it turns out, it has a plain ordinary every day meaning.

Livestock, of course, means “animals kept or raised for use or pleasure; especially : farm animals kept for use and profit.”3

And dead stock? Simply the “farm tools and equipment” and, the dictionary adds, as “opposed to livestock.”4

In other words, a farmer’s stock in trade that isn’t bleating, mooing, cackling, baaing or neighing, to be precise.

The things you learn poking around in court records…

SOURCES

- Auckland Court, Probate records 1863 P172/63; Last Will, Charles Trick, 20 July 1861; digital images, “New Zealand, Archives New Zealand, Probate Records, 1843-1998,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 24 May 2017); citing Archives New Zealand, Auckland Regional Office. ↩

- See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891). See also John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 24 May 2017). In both cases, the search terms “livestock,” “live stock” and “dead stock” were used. ↩

- Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.m-w.com : accessed 24 May 2017), “livestock.” ↩

- Ibid., “dead stock.” ↩

You left out oinking and braying.

Sigh… what can I say? I’m a suburban kid.

Hmmm, maybe I’ll add a codicil to my will leaving the dead stock to my older son. Now that should liven things up a bit in the probate judge’s office. Feeling mischievous….

Do it! 🙂

Yes I had similar in a family will of about 200 years ago.

So great to read your legal investigations include my country of birth. #kiwi

I have included your blog in either INTERESTING BLOGS or GENERAL INTEREST in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

http://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2017/05/friday-fossicking-june-2nd-2017.html

Thank you, Chris

Thank you!