Why results aren’t always the same

Reader Michelle Schohn found herself confronting a fairly common conundrum with her autosomal DNA test results.

“I took DNA tests in 23andme and Ancestry, and uploaded the results to gedmatch.com,” she wrote. “The tests are not a 100% match.”

So, she wants to know: “Why would that be?”

Great question, with a pretty simple answer but one that requires us to stop and take a look at exactly how this kind of DNA testing is done.

First off, remember that the DNA tests we’re talking about here are autosomal tests: the ones that test the kind of DNA we all inherit from both of our parents1 in a mix that changes, in a random pattern, from generation to generation in a process called recombination.2 It’s really useful for finding cousins who share some portion of DNA with us with whom we can then share research efforts.3

First off, remember that the DNA tests we’re talking about here are autosomal tests: the ones that test the kind of DNA we all inherit from both of our parents1 in a mix that changes, in a random pattern, from generation to generation in a process called recombination.2 It’s really useful for finding cousins who share some portion of DNA with us with whom we can then share research efforts.3

Second, remember that there’s a growing list of companies doing this kind of testing for genealogical purposes: Family Tree DNA (with its Family Finder test); 23andMe; AncestryDNA; MyHeritage DNA; and now, for ethnicity only at the moment, Living DNA.4

So if person A tests with one company and person B tests with another company, never the twain shall meet? No, that’s what Gedmatch is for. It’s a third-party site with mostly free tools (but some extra goodies if you pay for it) that allows those two people to compare their autosomal DNA results in detail at a level of analysis that isn’t possible otherwise.5

But if you upload your own results from more than one testing company — this is not recommended, by the way6 — you will see differences between them. Just the way Michelle did.

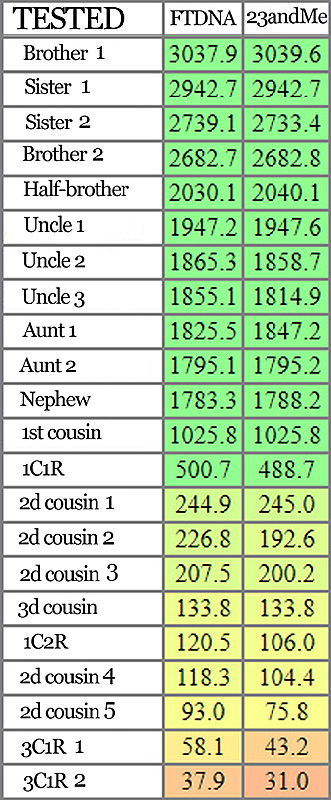

Take a look at the chart that’s illustrating this post. On the left are some of my top matches, identified by relationship.7 The first column on the right is the amount of DNA I share with these matches when comparing my Family Tree DNA test data; the second column on the right is the amount we share when comparing my 23andMe test data.

Not the same, is it?

And there are even differences when you run those two test kits through the admixture tools: using the Eurogenes K13 analysis tool, my percentages change a bit. I’m 44.51% North Atlantic using 23andMe data, and 44.55% using Family Tree DNA.

And I’m 0.95% Northeast African using Family Tree DNA data, and 0.91% using 23andMe.

So… why is this the case?

It’s because the tests aren’t looking at exactly the same parts of our DNA.

We all have 23 pairs of chromosomes as human beings, for a total of 46 chromosomes.8 In the aggregate, those 46 chromosomes contain roughly three billion base pairs. “The DNA molecule consists of two strands that wind around each other like a twisted ladder” and a base pair consists of “two chemical bases bonded to one another forming a ‘rung of the DNA ladder’.”9 Or, considering these are in pairs, six billion building blocks of DNA, called nucleotides.10

The tests, however, don’t look at all three billion base pairs or six billion nucleotides. If they did, they would be doing what’s called sequencing: “the process of determining the precise order of nucleotides within a DNA molecule.”11 It’s been done — the Human Genome Project succeeded in sequencing the human genome for the first time in 2003.12 It took 10 years and cost somewhere between 500 million and a billion dollars.13

It’s a lot faster and a lot less expensive now. By 2006, it was down to $100,000; in 2016, some tests were at $1,000; and one key player in the sequencing market is saying it will eventually get to the $100-a-test level where our genealogical tests were just recently and some still are today.14

To get the genealogical tests to the price level we pay — and already complain about! — the tests don’t look at “the precise order of nucleotides within a DNA molecule” using sequencing. Instead, they look at just the parts of the autosomal DNA that the testing companies think are particularly useful for their testing purposes, in a method called sampling or, using the term 23andMe uses, genotyping.

All of the companies, then, are looking at only some of the bits and pieces of our DNA, called single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs.15 At last report, 23andMe looked at 577,382 autosomal SNPs; Family Tree DNA about 690,000; AncestryDNA 637,639; and MyHeritage DNA 702,442.16

Each DNA testing company decides for itself which parts of the DNA are useful for their purposes: some of them like 23andMe and AncestryDNA are including areas that offer information about medical conditions and traits; others like Family Tree DNA specifically exclude those medical regions for privacy reasons and focus on areas believed to be relevant to matching people genealogically.

And, because the sample selected and examined by each company isn’t the same as the sample selected and examined by any other company, if you look at two samples in Gedmatch from the same person but from different testing companies, you get exactly the differences Michelle asks about and that you see in my results here.

Note that these are not huge differences. Whether in the matching or in the admixture (ethnicity) estimates, the differences are pretty small. They’re only going to make a difference when you’re right at the tail end of your 1000 most common matches, where one person may fall off the list faster than another depending on whether you’re comparing oranges to oranges (company A’s results to company A’s results) or oranges to tangerines (company A’s results to company B’s results).

Someday we will all be doing whole genomic sequencing, looking at every little nook and cranny of our DNA. In the meantime, there will be these very small differences company to company.

SOURCES

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Autosomal DNA,” rev. 9 May 2017. ↩

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Recombination,” rev. 21 Feb 2017. ↩

- See Judy G. Russell, “Autosomal DNA testing,” National Genealogical Society Magazine, October-December 2011, 38-43. ↩

- There are others testing for science rather than genealogy, such as the National Geographic Geno 2.0 project. ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Updated look at GedMatch,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 26 Mar 2017 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 30 July 2017). ↩

- The results are not all that different, and it clogs up the system. So if you must do this, make one of your results private. ↩

- Yes, I have a lot of siblings. Yes, I have a lot of aunts and uncles. Yes, I have a lot of cousins. What can I say? My mother’s family was prolific. ↩

- “Help Me Understand Genetics: How many chromosomes do people have?,” Genetics Home Reference, National Institutes of Health (https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/ : accessed 30 July 2017). ↩

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Base pair,” rev. 31 Jan 2017. ↩

- Ibid., “Nucleotide,” rev. 11 Nov 2013. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “DNA sequencing,” rev. 24 July 2017. ↩

- See “All About The Human Genome Project (HGP),” National Human Genome Research Institute (https://www.genome.gov/ : accessed 30 July 2017). ↩

- Ibid., “The Cost of Sequencing a Human Genome.” ↩

- See Matthew Harper, “Illumina Promises To Sequence Human Genome For $100 — But Not Quite Yet,” Forbes, posted 9 Jan 2017 (https://www.forbes.com/ : accessed 30 July 2017). ↩

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Single-nucleotide polymorphism,” rev. 30 Jan 2017. ↩

- Ibid., “Autosomal DNA testing comparison chart,” rev. 8 July 2017. ↩

“… or in the admixture (ethnicity) estimates, the differences are pretty small. ” — It may be better to emphasize here that you are writing about estimates from the *same calculator* (of whichever chosen at gedmatch) using two genotype data sets from different vendors.

Using different calculators can give very different results.

That’s correct: same calculator, different test data sets.

Lots of excellent information here about the testing companies and the process. I learned more about it. Thanks!

Thanks for the kind words, Randy!

If you test at two companies, your raw data will not be the same. The chips do not read the data perfectly and a few percent of the SNPs are marked as “no call”. Only about 99% of the SNPs will match in the two companies results. However, this does not have a great effect on the cM of matches between two people. I wrote an article on “Raw Data Comparison: FamilyTreeDNA vs MyHeritageDNA” a few months ago at: http://www.beholdgenealogy.com/blog/?p=2136

Great article. I did start to wonder about the accuracy issue also. If I test three times with the same company is there a good chance all three will come back exactly the same? Two of the three?

As long as the tests were on the same platform (same testing chip), the results should be the same. But Ancestry has had at least two chips, 23andMe has had three or four, etc., and so there are changes from one to another even within the companies.

There will be slight differences even at the same company even on the same version of the same chip because you probably won’t get no-calls on precisely the same SNPs each time.

Thank you for your reply. I had found a cousin who had tested twice at AncestryDNA using different usernames and his results were slightly different. I was confused as to why they were different and why a person would test twice with the same company. I contacted him and he verified that both results were his.

Great explanation but why if I upload the same raw data to two different companies do I get different ethnicities?

Because each company has its own set of people in its reference populations to which it compares your DNA sample.

You say it is not recommended to upload your own results from more than one testing company as “The results are not all that different, and it clogs up the system.”

Is there any one site that you would say is most optimal for the upload?

Tough question and no one good answer. What you might do is pick the kit that has the most matches >= 7 cM in the DNA File Diagnostic Utility.