True or false:

A marriage bond was an intention to marry — a reflection of an official “engagement.” A man who had proposed to a woman went to the courthouse with a bondsman, and posted a bond indicating his intention to marry the woman.

If you said true, all I can say is BZZZZZZT!!! Wrong answer.

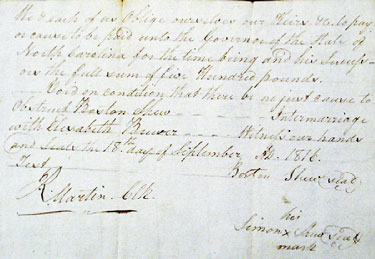

1816 NC Marriage Bond

I mean, yeah, okay, sure it’s true that you wouldn’t have gone and signed a marriage bond if you didn’t intend to get married, but simply “reflecting an engagement” or “indicating an intention to marry” is about as far from the real purpose of a marriage bond as it’s possible to get.

Remember that, for the longest time, the way folks got married was that marriage banns1 were read from the pulpit or posted at the door of the local church. Usually, banns were read on three consecutive Sundays or posted for three weeks.

For example, in Virginia, a 1705 statute required “thrice publication of the banns according as the rubric in the common prayer book prescribes.”2 In North Carolina, as of 1715, couples had to have “the Banns of Matrimony published Three times by the Clerks at the usual place of celebrating Divine Service.”3

That notice that two people were going to marry had one purpose and one purpose only: to make sure folks knew there was a wedding in the offing so that they had a chance to come forward and object if there was some legal reason why the marriage couldn’t take place.4 In general, that meant one (or both) of the couple was too young, one (or both) of them was already married, or the law prohibited the marriage because they were too closely related.5

When folks married without banns, however, particularly when they married some distance away from where they were known, there wasn’t the same opportunity in advance to have folks “speak up or forever hold their peace.” The bond then stepped into the breach.

What that bond actually was, then, was a form of guarantee that there wasn’t any legal bar to the marriage. Enforcing the guarantee was a pledge by the groom and a bondsman — usually a relative — to pay a sum of money, usually to the Governor of the State (or colony if earlier, or to the Crown if in Canada6), if and only if it actually turned out that there was some reason the marriage wasn’t legal. The bond shown here, for example, for the marriage of my fourth great grandparents in Wilkes County, North Carolina, in 1816, was a promise by the groom Boston Shew and his brother Simon to pay the Governor of North Carolina five hundred pounds, but it provided that it was “Void on condition that there be no just cause to Obstruct Boston Shew — Intermarriage with Elizabeth Brewer.”7

The use of marriage bonds was common, particularly in southern and mid-Atlantic states, well into the 19th century,8 when most jurisdictions started relying on what the couple said in a written application for a marriage license. And the laws about those… well… that’s a tale for another day…

SOURCES

- “Public announcement especially in church of a proposed marriage; plural of bann, from Middle English bane, ban proclamation, ban.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.merriam-webster.com : accessed 24 Jan 2012.) ↩

- Virginia Laws of 1705, chapter XLVIII, in William Waller Hening, compiler, Hening’s Statutes at Law, Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the first session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, 14 vols. (1819-1823; reprint ed., Charlottesville: Jamestown Foundation, 1969), 3: 441. ↩

- North Carolina Laws of 1715, chapter 8, in William Saunders, compiler, Colonial Records of North Carolina, Vol. 2 (Raleigh, N.C. : P.M. Hale, State Printer, 1886), 212-213; online version, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South (http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/), University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. ↩

- See generally Susan Scouras, “Early Marriage Laws in Virginia/West Virginia,” West Virginia Archives & History News, vol. 5, no. 4 (June 2004), 1-3. ↩

- Maryland by statute required marriages to follow the Church of England Table of Marriages, drawn up in 1560, that said when relatives were too closely related. Chapter 12, Laws of 1694; Maryland State Archives, Acts of the General Assembly Hitherto Unprinted 1694-1698, 1711-1729, vol. 38: 1 (http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000038/html/am38–1.html : accessed 23 Jan 2012.). For that table, see F. M. Lancaster, “Forbidden Marriage Laws of the United Kingdom,” Genetic and Quantitative Aspects of Genealogy (http://www.genetic-genealogy.co.uk/Toc115570145.html : accessed 23 Jan 2012.) ↩

- See Marriage Bonds and Licences, Library and Archives Canada (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/022/022-906.002-e.html : accessed 23 Jan 2012). ↩

- Wilkes County, North Carolina, Marriage Bond, 1816, Boston Shew to Elizabeth Brewer; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- United States Marriage Records, FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/United_States_Marriage_Records : accessed 24 Jan 2012). ↩

Quite interesting! Thanks for your insight.

Have a great day!

Ruth Stephens

Ruth’s Genealogy

Thanks, Ruth!

Judy I have a question about the marriage bonds. I have an ancestor who was dead before the dates of the marriage but the person is listed as bondsman. is it possible that a parent could have been listed as a bondsman after death by another person? it is a dilema

It’s highly unlikely, since the bondsmen usually had to appear in person.

so I found a record of marriage and it states — A Jno.S.C. McDonald signed for Security – does the word Security mean a bond was done

It doesn’t prove it, but it suggests it.

I had always wondered what the purpose of the marriage bond was. Great post!

So glad you found it useful!

I also have a North Carolina marriage bond in my ancestry. The 1809 marriage bond was taken out by William Clement as he prepared to marry Mary Brasfield. William was a member of a local Presbyterian Church. Thanks for your additional insight into this document.

Hi, Mary! Lots of NC marriages were by bond. Of course, the one I really want (my 3rd great grandparents Martin Baker and Elizabeth Buchanan) is nowhere to be found… Sigh!

To Mary Clement Douglas:

Mary,

Your ancestor William Clement’s name catches my eye. The reason why is too much to explain in a short note here. Which NC County was he from? Thanks.

I know this is old, but thank you for clearing this up. I was looking for such a bond for Constant Gray marrying Jane, Jinsey, Ginsey, Sale. Seems ther is one but ‘they” want money. I’ll keep looking.

If there is such a bond, it’d be at the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh.

OOPS, meant to say also in Wilkes County, NC.

Thank you for everything you do, Judy!! Were marriage bonds generally taken out the same day as the wedding?

I don’t know that we can say they were “generally” the same day as the wedding, Deidre, but certainly it was likely to the close in time.

Hey, I read your article because ia m new to geaneology and was curious as to who a bondsman was. First off, I appreciate your article and found it very illuminating. Secondly, your examples, Boston Shew and Elizabeth Brewer- they’re my fourth great grandparents as well!! Sorry…crazy coincidence 🙂

That’s terrific! Hello, there, cousin, and let’s trade info! Email me please (legalgenealogist (at) gmail.com)!

I’m curious what happens with the money that is paid, to the governor? I just found a Marriage bond for my 3rd great grandparents in 1829 in Virginia…$150…just wondering where does that money end up?

No money actually gets paid over unless and until the condition in the bond is found to exist, that is, a finding by a court that the marriage itself was illegal. It’s not payment of money by itself; it’s a promise to pay if and only if the marriage is illegal.

Thank you for answering my (unasked) question – no money changed hands unless the marriage was found to be invalid. Let me ask you another question – what if the marriage was found to be invalid, but the bondsman was either dead or could otherwise not pay the bond?

The only people who could be held liable were those who signed the bond. If one was dead, the other(s) would be responsible. If it was a matter of can’t afford to pay, there would likely be a court action to seek relief from the bond.

Thank you, thank you! I just found a nearly identical document to yours for my paternal 4x great-grandparents. Theirs was on the day of their wedding in 1847 in Ashe County, North Carolina. I understood the gist of the document (can I just say how amazing it is to see handwriting from an ancestor that is 168 years old?!) and another descendant and I could not figure out why in the world our ancestor would owe $1,000 to North Carolina. This explains it perfectly as they married away from home essentially and the bondsman was the bride’s brother. Thank you so much for helping me clarify my family history.

Excellent, Lisa! Glad this helped you understand the record!

I have several of these in my tree but did not know what they were for. Thanks for answering this lingering question!

Glad to help!

Thank you very much for this post. I have just found the 1798 marriage bond for my 4th great grandparents and wanted to know exactly what it meant. This post was exactly what I needed since the groom’s “co-signer” had my bride’s last name but it didn’t say specifically it was her father. Online trees have put this as her father for years, and I think it’s because they assumed it because of this record.

Thank you. This answered multiple questions, one of which was could a brother sign a bond instead of a parent.

I feel silly for having to ask this but I have marriage bond for Noah Moore & Mary Ann Hicks issued on 29 August 1841 & a license issued on 02 September 1841 issued in Bibb County, Alabama (both found at Family Search’s site), which date would they have actually been married on? I think on 02 September 1841 but am not positive.

It could be neither: the bond simply was the first step in the process, followed by the issuance of the licensed, followed by the actual marriage, which wouldn’t have been before the license was issued — but could have been on a later day.

Thanks so much for refreshing my old, old memory and raising another question. Was a marriage bond required only if the groom was not of marrying age? In other words, when trying calculate approximate birthdates when there doesn’t seem to be any other source, is it safe to assume that the marriage bond was used because the groom was under legal marriage age?

No, not at all. A marriage bond was required in many cases where both parties were of age, so you can’t draw any conclusions about age from the fact that a marriage bond was used.

Before your article, I couldn’t understand why fathers and prospective grooms were posting 50-pound bonds. It seemed like a lot of money in the early 1800s. Thanks for the explanation!

Glad you found it useful, David!

Really fascinating information and the bonds/banns might not be a bad idea these days! What was the typical period between posting of the bond and the actual marriage? My 5th ggrandfather posted a marriage bond on 22 May, 1850, in Northampton County, NC, but the record of the marriage is likely lost.

There is no absolute rule, but typically it was a matter of hours or days, certainly not months and rarely weeks.

Would a bond be required for a more mature marriage such as a widow well over twenty?

It could well have been required. Check the law for the time and place.

Very helpful as I research 18th & 19th century NC. Thank you!

Wow! I’ve seen lots of these types of documents for my ancestors. I made a lot of assumptions. One of my assumptions was that it was a sort of legalized dowry. This was enlightening. Thanks!

I have been a title examiner, oil and gas in WV for 5 years and looking at ancestry records from Doddridge County Roots the entire time and this is the first time I’ve ever run across the term ‘Marriage Bond’ my curiosity got the best of me and I had to visit your site. Speak now or forever hold your peace…….

Takes on a whole new meaning.

I see a marriage license in 2014, but it say Bond only. Is the person married or not.

You’re not providing enough details to allow me to offer an opinion.

I do legal work in the oil and gas industry, and if you Google Doddridge county roots they give a synopsis of a person’s life and the couple in question, I don’t remember who, took a marriage bond out. I do curative work which is a slightly fancy term for I look for dead people. And in my five years as a title examiner, abstractor, I have never seen that term. The CEO of the company never had either, it was a delight to explain to someone that has been in the business for 20+ years to explain what a marriage bond was. I am from Florida and moving to West Virginia has been an eye opener, culture shock, to put it bluntly. We live in a culture that take a marriage proposal very lightly, and learning thexperience facts presented to me by you research was refreshing and almost alarming, talk about a shotgun wedding!!

Judy could you plz tell ne how old a bondsman had to be? I have an 1841 bond for Delilah Sage born 1819 to marry Lewis Haga. Bondsman is Jonathan Sage. Her father James Sage was no longer living. Her brother was Jonathan born about 1820.

We sre told he was too young to have been bondsman……

She also had an Uncle Jonathan Sage…..

Thank you for any insight…Libby

In general, a bondsman had to be of legal age and owning enough property to support the amount of the bond. So someone born in 1820 would have been old enough to be a bondsman in 1841.

Apologies for not spell checking with my lovely wife on a Friday night after a trying week correcting everybody else’s mistakes please feel free to correct as you deem necessary.

I also have a marriage bond for my 3x great grandparents from North Carolina. My question is the use of the term “pounds” instead of dollars… Hasn’t dollars been our currency since immediately after the American Revolution?

Nope: although legally the dollar was the currency of the US after the Revolution, people still used pounds for decades. I have court records still referencing pounds in the 1830s.

Dear Judy G. Russell, I want to thank you for your Web Site! I came across a document in Ancestry.com for my Great Grand Father (James Russell of Milford Delaware, 1840-1891) and Great Grand Mother (Sarah Elizabeth Andrews of Milford Delaware, 1848-1928) and James T. Smith (I now surmise as Bondsman)dated Jan. 23, 1869 that confused me. I was not sure what it was until I found the title page [overleaf]. It said ‘MARRIAGE BOND’. My wife, Cheryl, looked it up on the internet and found your site.

Your explanation and your answers to your visitors brought it all to light!!!! When I meet [even on the internet] anyone who’s last name is Russell,I have to ask.. Are you related (either by blood or marriage) to either the Russell family, Andrews family or the Marshall family of Milford Delaware??

With extreme thanks to you again for your web site!

Sincerely, Donald K. Marshall

Glad you found the blog post helpful! But no… no relation to your Russells. (In my case, the name is anglicized from Italian and not really Russell at all.)

Dear Ms. Russell,

Oh well I thought I would try!!!

Thank you again for all you do!!!

It was very insightful.

Sincerely, Donald K. Marshall

Thanks for the kind words.

In the early 1850s my great great grandfather signed a marriage bond in Mobile, Alabama (penal sun of $200.00). What is the Purpose of such a bind?

It was exactly what this post says: “a form of guarantee that there wasn’t any legal bar to the marriage. Enforcing the guarantee was a pledge by the groom and a bondsman — usually a relative — to pay a sum of money, usually to the Governor of the State (or colony if earlier, or to the Crown if in Canada), if and only if it actually turned out that there was some reason the marriage wasn’t legal.”

Dear Judy,

Thank you for your post! I’ve just returned from a Virginia genealogy trip with boatloads of documentation. On the return flight, I spent quite a bit of time staring at a particular document trying to decipher the language. When I realized this document was a marriage bond, I immediately found your page upon researching. My question is regarding guardianship and the bondsman. Here’s the actual language of the bond:

1849 – Francis T. White

Taking proof & rescinding deed from Elizabeth Moughon 1,50

Taking bond and qualifying Richard W. Marchant as guardian to Rebecca Parrott – “86

I have no idea what the “86 is, or what the rescinding deed would be for. Also, who would Richard Marchant be to Rebecca? Your insight would be greatly appreciated in solving what would be a 5-year mystery of research.

I’d prefer to see the actual documents in context.

Thank you for such clear information. I am the historian for my family and I am so glad that I now understand this title.

Glad you found it helpful!

Thank you you this clear explanation. I have two marriages in question in Wilkes myself.

One person who may be a relative of mine, John Byers, appeared as a bondsman for Jesse Gullets marriage to Elizabeth Robarts in 1778. Also listed as bondsman was John Harmon. Both John Byers and Harmon were living on the land of little bury toney which was then transferred to Jesse Gullet. Is it possible they are all related or just that the bondsman rented land from him?

Way too many variables here to say anything more than — anything’s possible. The bondsman is certainly likely to be closely associated with the groom (or the bride) but saying more than that requires more research.

I have a question about making bond. Does the groom have to make bond where the bride to be lives?

The only possible answer is: “It depends!” The law of the time and place will say whether it has to be where the bride lives, or where the groom lives, or leaving the choice open to include any other location.

This was very helpful. We can’t completely read the first paragraph of the bond we found for my great great grandparents. We worried that he had paid to marry her.

Glad you found it useful!

Just wanted to add another “Thank You” for the information. I went and looked up information about the “banns” also. It’s fascinating to see how processes evolved over time!

I’m not sure if this is the appropriate place to as this question but;

We are searching for a Sarah Brewer that was born approx. 1777 in North Carolina. She married a George or Robert Headley. The had a son in 1995 presumable in Kentucky. Would you know if Sarah Brewer is the family to your Elizabeth Brewer from North Carolina? Sarah Headley married John Rawles in 1996 in Kentucky. A bond was posted in Kentucky. Thank you for your time

Roberta Headley

Roberta, I’m not sure — Elizabeth is one of the ancestors I need to research much more thoroughly. I don’t have a clear answer even as to who her parents were.

• In 1814 William Taylor and Catherin Maples obtained a marriage bond in Burke County, North Carolina-Mard Maples was the bondsman. (Mard Maples lived in Lincoln County, North Carolina.) In 1822 Andrew Wilson and Catherine Taylor obtained a marriage bond in Lincoln County, North Carolina-Marmaduke Maples was the bondsman. Then in 1830 and 1840 census for Lincoln County, North Carolina, Andrew Wilson lives next door to Marmaduke Maples. Since the same Maples was the bondsman, I’m thinking that the Catherine in each of these marriages are the same…yet it bothers me now that I find out that the bond for the prospective bride is supposed to be for the county she resides. I was thinking perhaps that Mard-Marmaduke Maples was Catherin Maples father.

Burke and Lincoln are next door to each other, and though the bond generally would have been filed in the county where the bride lived, there were always exceptions. There’s certainly reason to look at the Maples bondsman / bondsmen as Catherine’s family, but the bonds alone don’t prove father-daughter.

I discovered a L100 marriage bond signed in 1801 in Nova Scotia by both the groom and the bride’s father. However, I don’t think they ever married. Am I correct that altho a bond was undertaken, if the marriage does not take place then the bond is simply void?

Generally, yes, although the fact that it was written and recorded might require that it be formally voided if the sureties needed to free up the collateral from any possible claim.

Edgecombe county N.C. marriage records list the officiant of the marriage (of my grandparents) with the initials M.C. after his name. The date was 24 Dec 1879.What does this mean? The officiant has the surname Johnson which was the brides name but her father Benjamin Johnson was listed as a witness. I need to know who the M.C. was

Double check the initials (you can give me the info to check as well if you wish) but chances are really good it’s M G, not M C, and it means Minister of the Gospel.

I notice that most bonds name both the groom-to-be and the bondsman as joint guarantors. However, some are signed only by the bondsman, on behalf of the groom. Question: Did the groom-to-be have to be of age (over 21) in order to be named as a guarantor? Trying to pin down an ancestor’s probable year of birth!

Nope. What he had to be was a property owner — somebody the clerk would believe could pay the bond amount if called on.

I found a marriage bond for an ancestor in North Carolina where the bride’s name is not listed but the name of the groom and the brides father are. Her father was the one who put up the bond. Why would a father put up the bond and not her fiance?

In most cases, the groom was a young man with limited property, and he needed what was in effect a “co-signer” for the bond (a surety that the clerk knew would be financially responsible). That was often one or more members of the bride’s family or the groom’s family or — if a genealogist is really lucky — both families.

Q: Is there another post you made in follow-up to your concluding sentence here, “And the laws about those… well… that’s a tale for another day…”? I am wondering if those bonds and the condition of “no lawful objection” had anything to do with potentially negating marriages between two people of different races, or of mixed race. Many thanks.

Antimiscegenation laws would certainly be included, but that would be a much less common issue than a living spouse, too close a relation and the like.

What happened if the marriage was determined later to be illegal? Especially if the woman was already pregnant at the determination?

In theory, the amount of the bond could be collected from those who signed the bond. That was uncommon.

Hi, I was wondering do they still do it and how binding is it?

No. Marriage licenses have replaced marriage bonds.

Found this 10 years after you posted it but it’s very helpful. Was it common to see a marriage bond years after a marriage? I have ancestors in North Carolina that married sometime around 1790 (groom was 19 and bride was 12). 21 years and 12 children later they signed a marriage bond in 1811. Was this a common practice?

No, not normal at all, not common at all. I’d be inclined to say keep looking for another couple of the same names.