A society’s transcriptions raise questions

Reader Steve Dahlstrom was surprised when he ran across a website run by a local historical society that had transcriptions of a large number of obituaries from a local newspaper. The dates on the obituaries ranged, but many of them had been published well into the 1950s and so, he thought, would be covered by copyright. “My understanding of copyright would not allow websites … to transcribe and republish these obituaries without permission from the newspaper, when the original was published after 1922,” he says. And, if the newspaper did give permission, “should the webpage note this fact?”

Ah, yes. That oh-so-common, oh-so-murky question of whether newspaper obituaries are covered by copyright and when, where and how they can be used. Just about every question connected with obituaries and copyright law has to be answered with that most wonderful of The Legal Genealogist‘s answers. You know the one I mean. The one that has us all tearing our hair out.

It depends.

Oh, the “should the website say it has permission” part is easy. Sure it should. It always makes things easier. But the one Steve came across didn’t say whether it has permission. So now what?

Let’s start by going over some copyright basics.

First, anything that was published in the United States before 1923 is now in the public domain.1 That means there is no copyright restriction on it of any kind and you are free to use it in any way you’d like.2

First, anything that was published in the United States before 1923 is now in the public domain.1 That means there is no copyright restriction on it of any kind and you are free to use it in any way you’d like.2

So as far as any obituary published before 1923, it’s fair game and nobody has to be concerned about it at all.

Second, if something was published between 1923 and 1963 with a copyright notice — and most newspapers did include some kind of copyright statement somewhere in their pages — that copyright ended 28 years after publication unless the newspaper renewed the copyright by filing a registration with the U.S. Copyright Office and paying an additional fee.3 It may not be the easiest thing in the world to check to see whether a newspaper renewed its copyright — the records exist in an enormous card catalog in the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library of Congress — but my bet is that the vast majority of American newspapers didn’t bother renewing their copyrights on their archival editions.4

So assuming that the newspaper whose obituaries were transcribed by this local history group didn’t bother renewing its copyrights day by day after their initial term, any obituary published between 1923 and 1963 became public domain — fair game — 28 years later. An obituary published in 1950, for example, went into the public domain in 1978; an obituary published in 1960 went into the public domain in 1988.

Third, the fact that the obituary ran in the pages of a newspaper that was copyrighted doesn’t mean the obituary itself was covered by copyright — or, at least, not by the newspaper copyright. Remember that facts by themselves can’t be copyrighted.5 There has to be some spark of creativity for copyright protection.

So a newspaper that used a fill-in-the-blanks form and printed nothing but facts might very well not be able to claim copyright in the obituary at all.

Fourth, just because the newspaper published the obituary doesn’t mean the newspaper owns the copyright. Here again remember that whoever actually contributed that creative spark, that original expression, is the author and it’s the author who owns the copyright unless the author signs a written agreement giving the copyright to somebody else.6

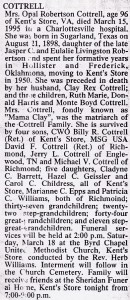

The obituary used here as an illustration happens to be my own grandmother’s obituary. It was published in 1995. But the newspaper that published it doesn’t own the copyright. It didn’t write one word of that obit. It was written by the family. I can even tell you specifically who in the family wrote the sentence about where my grandmother was born (because there has only ever been one cousin who kept insisting that my grandmother was born in Sugarland, even though my grandmother said she was born in Eagle Lake). And those of us who did contribute to writing it never signed an agreement to give the copyright to the newspaper.

This is a pretty typical example. Most obituaries aren’t written by newspaper staff — they’re written by the family or by the funeral home with information from the family. There are exceptions, of course — and you should be especially wary of using anything that ran with a by-line, that little section under the headline that identifies the writer.

So maybe the local historical society would need to ask us for permission to transcribe the obit and put it on a website. But it wouldn’t need to ask the newspaper.

And if those aren’t enough “maybes” for you, let’s throw in one more big one. It’s called the fair use doctrine, and it’s set out in federal law at 17 U.S.C. § 107:

the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means …, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include –

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.7

Even if something is copyrighted, you can still use some part of it if your use qualifies as a fair use. How does this use stack up against the statutory test?

• Transcribing old newspaper obits for a historical society to give away sure looks like a nonprofit educational purpose.

• The obit itself is mostly factual, so the nature of the work is given less protection.

• All of the obits ever published by one paper probably aren’t very much of the contents of the newspaper as a whole.

• And unless the newspaper is selling transcriptions, there’s not much effect on the market for the obit, is there?

So the transcription could very well be a fair use even if the newspaper does have a valid copyright. (By the way, I suspect most uses of single non-bylined obits of your own family members in things like blog posts would be considered fair use as well. Just sayin’ …)

And so, after all that, the answer to the question of whether the local historical society was violating the newspaper’s copyright is — brace yourself, you know it’s coming — it depends.

And we haven’t even considered whether the particular newspaper involved would think that having its name attached to every one of those transcriptions was a form of free advertising for its current editions … or that suing a local historical society over 50-year-old obituaries would be bad for business…

SOURCES

- See Peter B. Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States,” Cornell Copyright Center (http://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm : accessed 11 Sep 2012). ↩

- See generally “Where is the public domain?,” Frequently Asked Questions: Definitions, U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Sep 2012). ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 15a: Duration of Copyright, PDF version at p. 2 (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Sep 2012). ↩

- Do NOT take my word for it if you decide you’re going to go off and publish huge numbers of copies of pre-1963 newspapers. This isn’t legal advice and I won’t defend you. See

Judy G. Russell, “Rules of my road,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 18 Feb 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 11 Sep 2012). Make sure you check that card catalog! ↩ - See “What Does Copyright Protect?,” Frequently Asked Questions, U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Sep 2012) (“Copyright does not protect facts, … although it may protect the way these things are expressed”). ↩

- See “Who is an author?,” Frequently Asked Questions: Definitions, U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 11 Sep 2012). ↩

- “Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use,” 17 U.S.C. § 107. ↩

Thank you so much for addressing this topic. I’ve downed a fair amount of Rolaids recently trying to understand copyright as it applies to blogging so that I can stay on the right side of the law. I love your blog and I always learn so much .

Thanks for the kind words, Michelle — and I sure do understand the need for Rolaids…

Judy, as I understand it, it would be all right for someone to transcribe their ancestor’s obit from the actual printed newspaper (provided it meets the criteria above), but it’s not all right to transcribe the exact same obit using a PDF version found online(GenealogyBank, NewspaperArchives, Chicago Tribune Historical Newspapers)? Or is there a legal distinction between transcribing the information and publishing or posting that transcription?

Linda, there’s no question that you can transcribe the obit from the actual printed newspaper and, most likely, ANY transcription of the obit would qualify as what’s called a transformative use — a concept that’s part of the overall fair use test applied by the courts, because of the combination of the change in the format and the change in the use. (Caveat: I wouldn’t re-post or publish a transcription of every word of a by-lined, copyrighted obit without getting permission.)

The question as to where the obit came from is governed not by copyright law but by contract law. What do the terms of use of the particular website say? GenealogyBank‘s parent company NewsBank has said that text transcriptions are permitted under its terms of use; we’d have to carefully examine the terms of use of the other websites to see what they say.

And yes, there is almost always a difference between your own personal transcription, for your own personal use in, say, your genealogy database, and publishing or posting the information. Just about every website says in its terms of use that you can download and store snippets for your own personal research. It’s the re-posting or publication where the restrictions come in, and it’s important to read the terms of use or terms of service to see what’s allowed and where you’ll need to ask permission.

>>And yes, there is almost always a difference between your own personal transcription, for your own personal use in, say, your genealogy database, and publishing or posting the information.

Judy, this is where I have most of my confusion on. If I post a personal photo of a newspaper obituary, for example, in my FTM its one thing. But what happens when we use a cloud genealogy program such as Ancestry Member Tree? Doesn’t that change things because more than one person can see it (although I do have my tree private on there, there’s roughly 40 researchers working on it).

For copyright purposes, yes, Concetta, putting it out in public does make a difference because it’s the reposting, republication or copying that’s the issue under the law. And making it available to 40 people might well be enough to constitute publication. So if it is copyrighted, the absolute safest course is to ask for permission. It’s a rare case where permission isn’t given.

“Most obituaries aren’t written by newspaper staff”

That’s the convention TODAY. In times past, obituaries were typically written by the funeral home or by the newspaper, based on facts provided by the family.

“Transcribing old newspaper obits for a historical society to give away sure looks like a nonprofit educational purpose.”

That’s a stretch, and you know it. Publishing old obituaries on the Web may be informational, but it’s hardly instructional or pedagogic.

“we haven’t even considered whether … suing a local historical society over 50-year-old obituaries would be bad for business”

Are you implying that it’s OK because you won’t get caught?

(a) That’s why the answer is “it depends.”

(b) Fair enough — you can add in the scholarship and research purposes if educational alone doesn’t float your boat.

(c) No. I’m implying that the risk in the inevitable risk-benefit anaylsis of relying on fair use may be minimal at most.

Great post, great topic!

Thanks for the kind words, Dawn!

Hi.

I manage the Facebook page and am assistant editor of our state’s newsletter, The Carolina Herald, as well as the Old PEndleton District Chapter Newsletter. I would like to reproduce your post/article “Copyright and the Obit” in its entirity in our printed newsletters. May I do so with full credit being given to you and your site?

Thank you for your consideration.

Lesley Craddock

Yes, you have my permission, Lesley, and you might want to pick up today’s follow-up as well.

Merry Christmas Ms. Russell,

I greatly apologize for approaching this topic backwards…I am a volunteer member of Find-A-Grave. After hearing about so much concern about posting obituaries, I did some research and came across your “article” above. I posted most of it, along with credit to you and the link, so others could read your article too.

Another anonymous member has just contacted me, without expressing any concern of the content, but merely concern about “whether I have your permission”.

I had read the your immediate reply to “Lelsey” above, and…without giving it much thought…I assumed you would approve…

For my failure to contact you PRIOR to posting, I greatly apologize. Therefore, I am now asking for your permission. If you decline, I will gladly oblige and remove the posting from my Find-A-Grave profile. I truly meant no harm or offense.

Sincerely,

Steven Fairweather

I appreciate the courtesy of the request, and give my permission. Thanks for asking.

Btw, did that cousin and your grandmother ever get in an “argument” on where your grandmother was born? I can almost see the “fight” now!

Nope, the cousin took her position about where our grandmother was born after our grandmother’s death! Trust me on one thing, when it came to any issue, my grandmother won.

Can you explain to me how several websites manage to sell subscriptions to obituaries? This is mind boggling to me. Seems to me if an obituary is basic public knowledge about a deceased person then there should be no question about it, it is reusable for what ever purpose you want. Provided there is no by line author.

One such site charges $35 a month and advertises they have over 50,000 obituaries from my home state. I stopped and thought about that for a moment, heck, there’s more than 50,000 in books in the public library’s genealogy room and they were collected by the historical society and they state plainly inside the fron cover who to contact for a copy and how much that copy cost.

I think it would be absolutely awesome to have a website with all the obituaries ever published in any newspapers from all across the USA on it. That would take a tremendous amount of work on someone’s part and they should receive payment for their work. Collecting anything off old microfilm or even current news papers is time consuming. Plus the transcription efforts and then uploads to a website. No one wants to work for nothing.

Even historical societies make books of obituaries every few years and they sell them for a profit and the money is used for the historical society’s benefit. I haven’t seen an obituary book under $35.00

Even cemeteries are now collecting pictures and obituaries and making books to sell for profit to help with the up keep on cemeteries.

I realize it’s just an obituary, not rocket science or brain surgery, and I also realize that same obituary is also an historical document. One I feel should be more easily accessible than it is today. But OMG what an undertaking it would be!!!!

Let me know your thoughts,

BGH

It’s simple: as you say, “what an undertaking it would be!!!!” And because somebody has undertaken part of it at that somebody’s cost, they’re allowed to charge for your access to their efforts.Otherwise, you’d have to spend many times as much going to the location where the obituary was published, finding the newspaper in hard copy or on microfilm, and making your own copies. It’s no different from Ancestry charging for access to the census records, which are public federal records. You don’t HAVE to subscribe to Ancestry — you can go to the National Archives nearest to you and use the microfilm there. We’re paying for convenience.

A year or three ago I clipped an image of an obituary from the local newspaper and posted it on http://www.findagrave.com/ without thinking of the copyright issue. I soon received a nice email from a representative of the newspaper reminding me I should have asked permission, which she gave me.

I scanned through your great article and the comments (thank you!) but did not notice that suggestion. When in doubt, ask permission.

Always always always ask, if you can find someone to ask. It’s the safest of all possible worlds.

So if I am reading this correctly what a friend of mine and myself wants to do it legal? We are working on photo graphing all of the local cemeteries, we are wanting to put up the obits that we find for anyone in those cemeteries. We would also give a copy of them to the local library, the local historical societies, the holders of the cemeteries, ect. To do this since we are living in different locations we are looking at setting up a website that can have more added at our leisure. There would be other contributors from other areas. It would be able to be viewed by others on the web also. So as long as we site where the information was found it would be no infringement of copyright laws? Please help as we don’t want to get in trouble for helping others find this information easier. Please help as no one will give me a direct answer if this is something we can or can not do.

Nobody will tell you for sure because there are facts that will affect the answer. Are the obits after 1923 (if so they may be copyright protected)? Can you get permission to reprint from the newspapers involved? This is NOT a matter of citing your sources; it’s a matter of copyright law.

I am trying to find out if they will give me the permission, however, no one was in the area for my work to be able to be given permission yet. I am not sure either with all the other people that would be involved if it would be something that I can get done either. I already know one of them has permission from the papers to be able to do so, but the people here are not always the most cooperative on doing something like that. I will try to contact them again today as no one was there to answer questions on it yesterday. But I have also seen where people are saying that it isn’t always the paper that you need to get permission from it may be a family member that has to give it and that isn’t always the easiest to find out who did the obit either.

Your friend is correct that there may be others involved. But here’s a thought for you: facts cannot be copyrighted. The way they’re presented can be, but the facts themselves can’t. If you designed your own template for extracting information from the obits (name, date of death, spouse name, father name, mother name, siblings, etc.) and simply entered the facts without copying the way the facts were said in the obit, there would not be any copyright issue at all.

Thank you very much Judy. That helps a lot. I have just gotten in contact with our local news paper and I have sent them an email as he requested. So this should clear up a lot of the information that is available out there too. I will forward this on to a friend that is having an issue with what is going on with her on another website that we are working with to let her know that she can still add that information. I appreciate your time to respond to my questions and that it is being put in terms that we can understand.

I’m glad I can help at least a little! Remember, I’m not giving legal advice here — just explaining what I’d do in your shoes. (I have to repeat that disclaimer every so often…)

Thank you Judy, for clarifying that “facts cannot be copyrighted” and that I can post these facts in my own words. Your column answers some questions, yet because there are gray areas, I am going to create a template to use in relaying facts gleaned from obits. I have made it a habit to include a disclaimer stating that the names of family members are not included, unless proven they are deceased, as well.

My question is this: May I add in this disclaimer that I would email the obit to anyone upon request? I’m not liable for how they use it, am I?

Thank you!

Making a copy of the obit may very well violate the underlying copyright in the obit. Extracting the factual information isn’t a copyright problem, but making a copy is one of the exclusive rights the law gives to the copyright holder.

Is it possible to get copyright permission for every obituary a paper ever published with a single form? I work at a library that is looking to make all of our local obituaries (with the original scan from the paper) available in an online searchable database. This will obviously require us to get copyright permission from our local paper.

It isn’t very practical to request permission for every single issue of the paper. So, I’m wondering if one copyright permission form can cover everything? Also, if we wanted to keep the database current would we then have to get permission for each additional obituary or is there a way to cover future publications?

I’m not in a position to give specific legal advice, Ryan — this is something your library’s lawyer and the newspaper’s lawyer need to work out between them.

Judy, I would appreciate any insight you could offer on the following issue: Would I need permission from a copyright holder to publish an index of obituaries on the Internet? The index would be the decedent’s name and the name, date and page number of the newspaper in which the obituary is found. The actual obituary would not be reprinted–no image and no text. Would I need to contact the newspaper or the obituary copyright holder? Could I charge a subscription fee for web-site users to access such an index?

Subject to my usual caveat that I do not provide legal advice and that you need to consult a licensed professional in your jurisdiction if you want to have advice you can rely on, I can’t imagine that you’d need permission to report a fact: namely, the fact that an obituary was printed on page x of newspaper y on date z about Person A. My own view is that wouldn’t change whether the index was free or not — it’s simply reporting a fact, and facts can’t be copyrighted. But remember the caveat: this isn’t legal advice.

So what if I decided to compile and publish a collection of obituary transcriptions from a given newspaper from, say, 1900 to 1920. I could legally sell such a collection and be fine? Even if the newspaper is still running today and using the same title they did during that span?

Yes, absolutely, because anything legally published in the United States before 1923 is now no longer copyright-protected. It is in the public domain. You couldn’t copyright the collection (except as a compilation and except for the materials you yourself wrote and added) but you could publish and sell it.

Could you do this for dates AFTER 1923? For instance, could you simply index and list names and information from more recent newspaper obituaries without copying language…only the facts listed? If I wanted to do this for, say, USA Today from 1975 to 1980, would it be legal?

Facts can’t be copyrighted. If all you are doing is indexing facts, the Feist case would suggest that you could not be (successfully) sued for copyright infringement.

I have photocopies of obituaries for my great-grandparents from 1928 and 1929, but nowhere is the newspaper that they were published in identified. How can you ask permission if you have no idea who to ask? What if the local newspaper is no longer the same? Does any copyright die if the publisher goes out of business? Great article BTW!

The copyright continues for the time allowed by law. In general, a newspaper published in 1928 would have been copyrighted if published with a copyright notice, but the copyright would have had to have been renewed to be still in effect today. An estimate is that only about 15% of all copyrights were ever renewed. You can also consider whether your use of the obituaries would be fair use today even if they are still copyrighted.

I’m writing a genealogy book for publication on my wife’s family. I’ve reached out to one newspaper that continues to publish for permission to include the death notices and received approval. There is another newspaper in SW Nebraska, the Dalton Delegate, that ceased publication in 1951 and I cannot find who to request permission. The death notices were from 1930 and 1937. Thank you for the work on your website!

Two things to check out: (1) did the newspaper business file anything with the secretary of state of the state indicating who was handling its business affairs when it stopped publication? (2) did the newspaper initially file and then renew its copyrights for the time period? The latter requires some research at the US Copyright Office, but in general only some copyrights were ever renewed. See footnote 8 to Peter Hirtle’s chart, https://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm

After checking those two things, can’t he eventually fall back on the “good faith effort” thing?

There’s no such thing for copyright in the US. The “fair use” exception has nothing whatsoever to do with how hard you tried to find the copyright owner.

Thank you for this article. It addresses an important topic and I hope you don’t mind me sharing my experience with trying to see who owned letters submitted to newspapers.

I was interested in using them in a publication, so two years ago, I contacted several papers to ask if they owned the copyright for reader submitted content.

All but one tried to charge for reprints. Many have special services that handle the requests, and each one misrepresented their right to the copyrights, even when the letters had already passed to the public domain.

The only honest one was the New York Times. One of their editors responded via email specifically stating that they do not and could not assert a copyright over reader submitted materials that they published.

Again, thank you for clarifying the issue.

It’s appalling that so many outfits misrepresented the copyright status of the materials. Truly appalling.

I need help in correcting my mom’s obituary from 1987. We need to add something to it. I hope u can help.Thanks, Patricia

You can always write up anything that needs to be documented in your own genealogy and ask to have it included in any genealogy sites that use the previously-published obituary, but there really isn’t any way to “correct” something that was published 30 years ago.

I believe the family owns the obituary, not the funeral home or newspaper. The reason is the family PAID the funeral home for the service through their fees to assist in writing the obituary. The newspapers charge to have the obituary published and this charge is added to the funeral home fees. With fees being paid by the family, the obituary belongs to the family and is not copyrighted by the funeral home or newspaper If would be copyrighted, it would belong to the family. What are your thoughts.

Nope. The law is crystal clear on this. Unless there is a written agreement to the contrary, ownership of the copyright as to any work of authorship belong to the author. That written assignment of the copyright is the piece you’re missing in your hypothetical.

I must confess I had the same logic about families being the authors of these newspaper obituaries. I always thought a copyright was only extended for “original works” of an author, and certainly neither the newspaper nor the funeral home sites “should” claim such ownership for obituaries. I doubt most families in a time of grief would even understand they may be signing away their rights so the newspaper can own and profit from it. An obituary is so much more than cold basic facts which, by the way, can be input on genealogy websites without an obituary. I could tell the love that was poured into the words by family in their time of grief by the wonderful things said about their careers, their dedication and their character in many cases. To share only the cold “facts” even seems like an injustice when memorializing one’s time on earth. After reading these blogs, however, I apparently need to rethink the way I do things going forward. What I have posted was never intended for any kind of profit or infringement, but rather to verify relationships, and to establish a legacy for later generations who did not have the opportunity to know them. Great blogs. Thanks for your insight!

It’s important that we all really stop and think what we’re doing with other people’s work — and how (when, if and where) we can re-use it properly.

I was following your comments on copyright issues for obits; however, I didn’t see any mention of contents in obits that may be improper to publish regardless of permissions. If an obit is published on Find A Grave for instance, and there are minors or living members of the family whose names were published, is this not a violation of privacy laws or endangerment to minors regardless of obtained copyright permissions? Could there by more laws going on here other then copyright such on content?

Thanks.

There are no laws on this, no — you can’t say, for example, that it’s illegal to publish it online if it was legal to publish it in the newspaper. It may well be unethical for a genealogist under our genealogical codes of ethics, and it may be very unwise, but it isn’t illegal.

I have a very interesting situation that I’d love your take on. My mother passed away in March 2015 of pancreatic cancer (29 days from diagnosis to death).She penned her own obituary the day she was diagnosed. She read it to my brother, father and I are on her deathbed in hospice. I have the laptop she wrote it on. There is no doubt her creative spark, and gift for writing, created a work of art.

After her death, I submitted it to our local newspaper for publishing (and let me tell you – we’re all in the wrong business for the amount of money we paid). I suspected it would get a little attention because of its uniqueness, its humor and sweetness and the fact that I have some good friends in the media who would recognize a good story.

Sure enough, it received local media attention via a newspaper article. Then local TV. Then national media came calling. The Today Show. Good Morning America. Huffington Post. People Magazine. Inside Edition. The New York Times. Cosmopolitan Magazine. Fox News. Thousands upon thousands of shares on Facebook.

An incredible gift from my mom for sure. But then something weird happened about six months later. An identical obituary was published in Roanoke, Virginia – with only the names and dates changed. I was speechless. Turns out, a woman took my mother’s obituary and used it for her own mother. Local media in Virginia covered it as a unique story – and fawned all over the lady. That is, until I caught wind of it, and promptly contacted the local tv stations and newspaper to share that the obituary was indeed plagiarized. So additional stories ran about the plagiarized obituary. Case over, right?

Nope. It happened AGAIN about six months later. This time a family in Montana plagiarized it for their dad. Again, it began to go viral in Montana – and it wasn’t until I had a conversation with the gentleman’s daughters that we closed that chapter.

But you guessed it – it happened a third time. This time a woman died of an overdose, and her family plagiarized the obituary for their loved one. But because of some family dysfunction, and family members claiming there was no way their family member was this full of sunshine and rainbows, it created a divide in the family. I didn’t get tipped off until a reporter contacted me – and he thought his instance was an original case of plagiarism. I think he was disappointed to find out he was the fourth….that I knew of.

Turns out, that call prompted me to do some more digging. I found more than a dozen other instances of the obituary being plagiarized – either in whole or in part. Flabbergasted is an understatement of how I felt. I contacted a number of funeral homes and newspapers, requesting that the offending obituary either be removed or that attribution be given. In some instances, newspapers immediately recognized the issue once I pointed them to the original and they did a side by side comparison, while others (small funeral homes) didn’t quite know what to do since they now had to contact grieving families with a strange request. What a mess!

So now what do you do when your mom’s final love letter to her family is so amazing that folks around the country are now stealing it for their own use?

You grab a bottle of wine and build a website, hoping that perhaps as folks Google, they stumble upon the site and learn that plagiarism is wrong, but that if they love the words so much, I’d be happy to grant permission to reprint or use with attribution.

Cut to today, May 9, and I learn that a published cookbook (on sale at numerous stores and online) has printed an excerpt from the obituary (along with numerous others) without requesting permission from anyone.

And so the story goes – and I just can’t believe (though my mom always was bigger than life) there’s yet another chapter to what my family and friends now call obitgate.

Your post on copyright intrigued me in light of the issues we’ve been dealing with – as newspapers are very quick to remove the obituary as soon as I use the phrase “copyright infringement.” It’s been an odd 3 years, and the irony of me learning about this new issue on the eve of Mother’s Day weekend isn’t lost on me at all.

I find it a fascinating tale in plagiarism, copyright and ethics, and in fact, I now give a presentation about it. I mean, who on earth plagiarizes something as personal as an obituary? Turns out, lots of people do. I guess folks see things on the internet and assume it’s up for grabs – but I’m doing my best to educate folks and instead, ask folks to use my mother’s obituary as inspiration for themselves and their loved ones. Everyone deserves their own story, as far as I’m concerned.

Many thanks for letting me share my unique story. I know of no other one like it!

Flabbergasted doesn’t begin to describe it. And, yes, unfortunately, it’s exactly the fact that so many people think anything online is free for taking. Hope your voice added to all the others starts convincing folks that it’s wrong.

Judy, thank you so much for this outstanding article. It prompted me to revisit the language in the copyright law and I see your point regarding what information used is a fact versus a creative “original work of authorship,” as defined in section 102 of the law.

It then led me to Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co., 111 U.S. 53 (1884), and that led me to a new (but related) question: to what extent are photographs copyrightable? In Burrow-Giles the plaintiff argued that photographs are not art and only a mechanical process. The plaintiff lost because the person taking the (portrait) picture in this case added artistic value

“by posing the said Oscar Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation, made entirely by the plaintiff, he produced the picture in suit.” (Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884).

If a photo is of a gravestone, how is it even possible that “art” can be added to such an ordinary photograph of an inanimate object?

First off, photographs are specifically included as copyrightable items in the current copyright statute (see 17 USC §101, definitions, including photographs in the definition of “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works”). Second, case law has held that when a photo is nothing more than an exact copy of something else (a museum piece or, in your hypothetical, a tombstone), then it isn’t original and doesn’t qualify for a copyright. See Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1999). But using the theory of Burrow-Giles, most photos — even those of tombstones — aren’t mere copies: the photographer applies skill and creativity in lighting, angles and more in capturing the image. In other words, of course, the answer is: it depends!

It seems from your responses that a family member who authors an obituary is NOT considered the author – the newspaper is. I have a question, however. I wrote my father’s obituary in April 2010, and provided it to the funeral home who posted it on their site and they provided it to the newspaper. I used the same on the handout I created for the memorial service which was printed BEFORE I submitted the obituary to the funeral home and they to the newspaper. Does the fact that I have proof that I wrote it and I published it (printed it) prior to it appearing in the newspaper prove that I am the author as far as copyright is concerned or does ownership still belong to the paper that I paid to publish the obit. Thank you.

I’m not sure why you think the family member wouldn’t be considered the author. Whoever creates the work (the photo, the obit, the article) automatically owns the copyright unless, in writing, the rights are transferred. Unless your contract with the newspaper transferred ownership to the newspaper, you own the copyright on your own work.

Thank you for your incredibly prompt response. My question arose as you explained that the newspaper typically holds the copyright for obits. If they receive obit from funeral home, and don’t know obit was authored by a family member, newspaper would understandably assume they hold the copyright. How should a person prove authorship to retain the right to post or publish the obituary/tribute? Would a notice at the bottom of the obit be required? Thank you again for sharing your knowledge on obits and copyright!

I have collected well over 2000 Africam American funeral programs, complete with obituaries. If no copyright is printed on them, are they safe to publish as a compilation?

It’s not safe to assume they’re free of copyright just because there’s no copyright notice. You’re going to need to divide these based on time frame. See the chart Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States for the time when notice might be significant.

Thank you: I really appreciate this one.

Has any of this changed? And someone keeps saying “a blogger got sued” for bad information. Of course, nothing comes up in google. The “fight” going on at the moment, a person wants to use the obit of her father from a website on her tree. Some encouraged her to get a screenshot of the obit she wrote. Then it was commented that the obit was copyrighted by the website and not to do it!

thank you kindly for your time.

The law remains the law: the writer of the obituary holds copyright unless that writer transfers ownership in writing to someone else.

May I print your original post, Copyright and the obit of Sep. 12, 2012, for my own use and referencing. Not to be used in reprinting or publishing of any kind.

And in asking that, can responses, questions and answers also be printed? Certain things were brought out that would be good to keep in mind.

Thank you for your consideration.

Solely for your own use, yes. If you were going to share it with others, you’d need the permission of all the commenters.

This is a good resource for those of us who do online genealogy. I know the original was written in 2012 and people seem to have gotten a lot looser with their online privacy but I just hate it when I see an obituary copied and posted on one of these sites that has all the names and locations of the living relatives – especially when it’s MY name. But my question for you is, you said if something was posted between 1923 and 1963, the copyright ends after 28 years unless the newspaper extended. But what about the years after 1963? Did the rules change after that? Is it safe or not safe to copy and paste an obituary from 1972? Thanks!

The copyright might have been renewed. You can check this chart here at the Cornell Library Copyright Information Center for the way things worked thereafter.

What bothers me most, companies (like legacy dot com) who algorithmically scrape Obits from private Funeral Home domains (Immediately after posting) and surround the Obit with advertisements that financially benefit ONLY themselves.

This practice allows these companies to dominate top rankings on search engines, smothering visibility for the actual posting site.

As a family member who recently wrote an Obit for my mother, I witnessed this 1st hand. Moments after posting the Obit onto the Funeral Home website, it was hijacked by previously mentioned company. Now, my mothers Obit is surrounded by advertisements for flowers, competing Funeral services, head stones, etc.

Love to know thoughts on this…

You have the right as the author of the copyright (and therefore the owner of the copyright) to insist that it be removed from any site where you did not authorize its publication.

It’s my understanding that Legacy[dot]com has agreements with newspapers and funeral homes to publish their obituaries. There is no unauthorized data scraping going on there. As of 2020 they were partnered with “more than 1,500 newspapers and 3,500 funeral homes” according to their website.

Super interesting and helpful article, Judy, but I’m still a little confused. I’ve been copying obituaries from newspapers dot com and pasting them into FamilySearch for years. I thought I was doing a service to other researchers who can’t afford a newspapers dot com subscription (It’s fair use if it’s just for personal research/providing additional evidence for facts about a person, right? No profit is being made by anyone.), but now I’m worried I may have been unknowingly violating copyright laws for obits published after 1928. Do you have any advice for me? Thanks!

A much better choice would be to extract only the facts from the obits (since facts can’t be copyrighted) and post those.

Question : I see this article was written in 2012 and says anything before 1923 is now public domain. Does this become a year longer as each year passes, so now in Jan 2026 (i.e.Sep 2025 minus Sep 2012 = 13 years later) does1923+13 = mean anything before 1936 is public domain ?

How does it affect the wait +28 years to the “between 1923 and 1963” period ? Is that now “between 1936 and 1976” ? And what about things published 1964 and later ? I’m assuming they are all still under copyright ???

Could you please add an update/addition to the article to state how the passage of time affects copyright for folks seeing this blog for the 1st time all these years later, along with my other questions ? Also, add a link to the follow-up you mention in “Yes, you have my permission, Lesley, and you might want to pick up today’s follow-up as well.” Thanks !

https://www.legalgenealogist.com/2026/01/02/welcome-to-1930/