150 years ago today

He was 12 days short of his 23rd birthday when he enlisted on the 17th of February 1863 at New Bedford, Massachusetts, for three years.

He stood 5’9-1/2″ tall, had black hair, brown eyes… and black skin.1

He stood 5’9-1/2″ tall, had black hair, brown eyes… and black skin.1

And 150 years ago today, he showed a level of courage and dedication to the flag of the United States that, eventually, made him the first African American ever to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor.

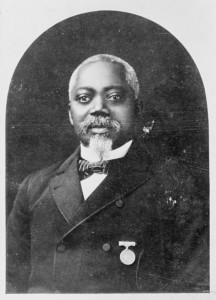

His name was William Carney. He was a member of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

And 150 years ago today, that entire unit showed a level of courage and dedication to the cause of the United States that many in both the North and the South had said would never be seen from a unit like the 54th Massachusetts.

A unit of African Americans.

The 54th Massachusetts had only been formed in early 1863. More than 1,000 men had answered the call of Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts and headed off to training camp. And it wasn’t until May 28, 1863, that the unit — 1,007 black soldiers and 37 white officers — began their journey to the battlefields far to the south after a rousing send-off at the Boston Common.2

The troops of the 54th were barely six weeks into their military experience when they were called on to lead the charge at a place called Fort Wagner, a Confederate stronghold that guarded the port at Charleston, South Carolina.

The charge that took place 150 years ago today.

The charge that — under the laws of the Confederate States of America — made the men of the 54th Massachusetts and all similar units subject to vastly different treatment from other Union soldiers if they should have the misfortune to fall into Confederate hands.

Under Confederate law, passed just weeks earlier, the men of the U.S. Colored Troops weren’t to be treated as prisoners of war if captured. Instead, their white officers were subject to the death penalty:

Every person being a commissioned officer, or acting as such, in the service of the enemy, who shall, during the present war, excite, attempt to excite, or cause to be excited a servile insurrection, or who shall incite or cause to be incited a slave to rebel, shall, if captured, be put to death or be otherwise punished, at the discretion of the court.3

And the soldiers themselves? Sold into slavery:

All negroes and mulattoes who shall be engaged in war, or be taken in arms against the Confederate States, or shall give aid and comfort to the enemies of the Confederate States, shall, when captured in the Confederate States, be delivered to the authorities of the State or States in which they shall be captured to be dealt with according to the present or future laws of such State or States.4

The law wasn’t the first time the Confederacy had taken such a harsh view towards African American soldiers and their officers. Jefferson Davis had issued a proclamation earlier to the same effect, and the resolution was just confirming it.5 And it was clear that the Confederacy wanted the newly formed U.S. Colored Troops to know about these laws. It wanted to take the heart out of the men and discourage their officers.

And the men of the 54th knew about the Confederate laws. They’d been told. When their colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, spoke to the men just before that charge, he reminded them that even in the North there was doubt about their fighting abilities: “I want you to prove yourselves. The eyes of thousands will look on what you do tonight.”6

And so they did.

As a unit, though they didn’t succeed in taking Fort Wagner that night, they proved their fierceness in battle.

And as individuals. Individuals like William Carney, the now-23-year-old sergeant of the 54th Massachusetts. Who threw away his gun when he saw the man carrying the American flag go down, so he could take up the colors. Who fought his way, on his knees at times, to the top of the ramparts of the fort. Who didn’t give up the flag even when the unit retreated. Even when he was hit twice by bullets. Even when he made it back to the Union lines:

I met a member of the One-hundredth New York, who inquired if I was wounded. Upon my replying in the affirmative, he came to my assistance and helped me to the rear. While on our way I was again wounded, this time in the head, and my rescuer then offered to carry the colors for me, but I refused to give them up, saying that no one but a member of my regiment should carry them.

We passed on until we reached the rear guard, where I was put under charge of the hospital corps, and sent to my regiment. When the men saw me bringing in the colors, they cheered me, and I was able to tell them that the old flag had never touched the ground.7

For that conspicuous bravery, Carney earned the highest honor this country bestows on its military, the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was the first African American to earn it, though it took 37 years for the medal finally to be awarded to him.8

He wasn’t the last member of the U.S. Colored Troops to earn it; the 54th Massachusetts wasn’t the only USCT regiment to show courage and fortitude in making a distinct contribution to the Union victory in the Civil War.

All in spite of — or, you have to think, perhaps, at least in part, because of — the laws of the Confederacy.

SOURCES

- Regimental Descriptive Book, Records of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored), 1863-1865, entry for William Carney; digital image, Fold3.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 10 Feb 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M1659, roll 2. ↩

- “The 54th Massachusetts Infantry,” History Channel, http://www.history.com/topics/the-54th-massachusetts-infantry (accessed 17 Jul 2013). ↩

- §5, “Joint Resolution relative to the subject of retaliation” (1 May 1863), Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861-1865, vol. VI (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1905), 487-488; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 17 Jul 2013). ↩

- Ibid., §7. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “The 54th Massachusetts Infantry,” History Channel, http://www.history.com/topics/the-54th-massachusetts-infantry (accessed 17 Jul 2013). ↩

- Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keydel, compilers, Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won the Medal of Honor (Detroit : Perrien-Keydel Co., 1901), 258-259; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 17 Jul 2013). ↩

- See Letter from William Carney to General Fred C. Ainsworth, 25 May 1900, acknowledging receipt of the medal; Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1762 – 1984; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; digital image, Archives.gov (http://www.archives.gov/ : accessed 17 Jul 2013). ↩

Great post, as usual, Judy! And, perhaps, more appropriately timed, than you will ever know!!

Thanks, Mary Ann… and wondering about that timing comment…?

Judy, just a reference in my mind to the current chaos over the Zimmerman trial. We need so badly to have a real conversation in this country about what the color of your skin means, and to whom. And it needs to be a conversation based, I think, on “positive” notions. A long time ago, when I was a child, I thought all of the controversy over skin color would all go away by the time I was grown. And in those 70+ years it hasn’t happened. This positive article and others like it can, perhaps, be a starting point to talk about how much alike we all are. I’m just distraught about how much the outcome of this trial has split certain factions of our communities, and I have no ideas for how to “fix” it!

Ah… I’m a little slow today. Yes, yes indeed, yes absolutely. We have GOT to get over the idea of superficial differences when there is so very much that makes us alike.

And of course the movie “Glory” (1989) starring Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman was about the 54th Massachusetts and the assault on Fort Wagner.

That it was, and William Carney’s role was shown in the movie.

Yes, I agree that the courage and fortitude was in part Because Of the laws of the Confederacy. If you take that back far enough, of course, the entire war was energized in (large) part because of the “laws” of slavery, and these special military laws simply extended those. Even today, black men are often burdened with proving themselves against racist stereotypes. Wasn’t it Denzel Washington who carried the flag in the movie “Glory”? I don’t remember the movie mentioning Carney, but I’m glad to know this full history. Thanks!

I think you’re right that Carney specifically wasn’t mentioned; the role of all the color bearers was rolled into one, I seem to recall.