Next in an occasional series on copyright — the foreign letters

Reader Cynthia Shenette has what she describes as “a wonderful pre and post WWII collection of letters, so informative and at times heartbreaking.” She hasn’t yet published them, in part because of “the sensitive nature of some of the content.” But now with the passage of time, she writes, “I would love to revisit them and consider posting some of them on my blog, but I do not want to violate the writer’s copyright.”

Complicating the question for Cynthia are the facts that the letters were written by family in Poland, and that they have been translated into English by a cousin.

Complicating the question for Cynthia are the facts that the letters were written by family in Poland, and that they have been translated into English by a cousin.

Under these facts, what’s the copyright status of the letters?

Great question, and The Legal Genealogist was delighted that Cynthia recognized that there are four issues here: (1) the ownership of the letters themselves; (2) the copyright interests of the letter writers; (3) the copyright interests of the translator; and (4) the fact that these were written in Poland, not the United States, and so the law to be applied may be different.

Now before we tackle these questions, I need to do my disclaimer bit again. Always remember that I’m commenting generally on the law here and not giving legal advice, and you may want to consult your own attorney, yadda yadda yadda.

Ownership of the letters

This is the easiest part of the entire problem. Cynthia noted that the letters came to her as part of her grandmother’s papers, and adds: “I am the legal heir to my grandmother’s papers as they were left to my mother and then to me.”

So there’s no question here about Cynthia’s legal ownership of the letters themselves. They’re hers. But as Cynthia recognizes, that leads to the next question.

Copyright of the letter writers

Owning specific physical items — these letters themselves — is entirely separate and apart from owning any copyright there may be in the items. The U.S. Copyright Office explains that:

Mere ownership of a book, manuscript, painting, or any other copy or phonorecord does not give the possessor the copyright. The law provides that transfer of ownership of any material object that embodies a protected work does not of itself convey any rights in the copyright.1

Neither Cynthia’s grandmother nor her mother owned the copyright to letters written by others. The letter writers themselves owned those rights and Cynthia doesn’t have any evidence that they ever transferred those rights, or intended that they be transferred, to her grandmother or mother.

So if there is still copyright protection of the letters, it belongs to the writers or their heirs.

Copyright of the translator

Cynthia is also correct to note that there’s a question of the rights of the translator, her cousin.

It’s a given that copyright law — both in the United States and internationally — protects original works.2 A translation, on the other hand, is by definition a derivative work, but even so “may qualify for copyright protection by possessing sufficient originality.”3

Huh?

Let’s break that down. The first part of that sentence is talking about the legal relationship between the original authors — the letters writers — and the translator. The second part is talking about the legal relationship between the translator and anybody else who wants to use the translation.

Under the first part, the hefty legal rights are those of the original author, because the translator’s work depends on — derives from — the original. That’s why the second word, the translation, is called a derivative work. If the translator wants to publish his or her translation of someone else’s work, the translator has to get the permission of the original author or authors. Just translating a letter for its recipient or for private use without publishing it isn’t a problem and doesn’t require permission.

Under the second part, even if the original document is out of copyright or the author has given permission, anyone else who wants to publish the translation needs the permission of the translator, because the translator has put enough of his or her own original thought into the translation. (If you don’t think original thought is required for a translation, try a machine translation one day.)

In Cynthia’s case, the translations were done by “a cousin who has given his permission to post his translations” on her blog. So she’s covered there.

Three down, one to go.

Copyright law in Poland

The last part is the trickiest part, and Cynthia gets high marks for recognizing that there really is an issue of international law here. The letters were written in a foreign country, and there’s always the chance that the law of another country will be different from the law here in the United States.

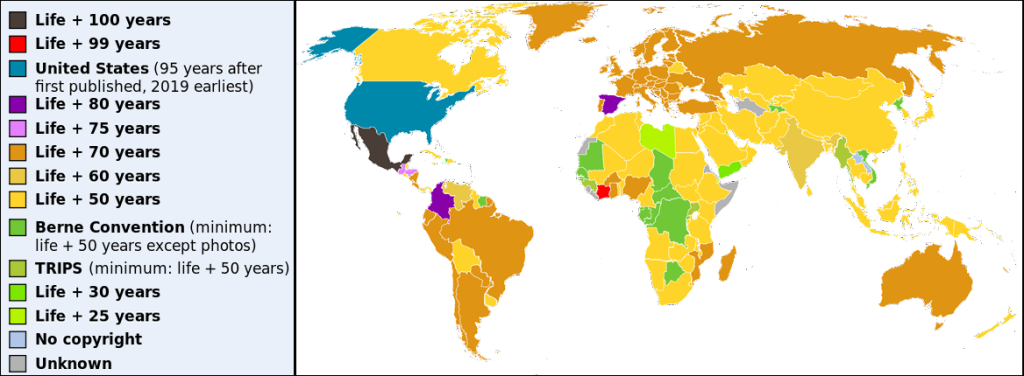

For copyright, in fact, there’s a pretty good chance the law won’t be the same, as this map shows (click to enlarge):

The question of which country’s law will apply when letters are written in country A and sent to country B isn’t an easy one. There can be what’s called a “conflict of laws”:

A difference between the laws of two or more jurisdictions with some connection to a case, such that the outcome depends on which jurisdiction’s law will be used to resolve each issue in dispute. The conflicting legal rules may come from U.S. federal law, the laws of U.S. states, or the laws of other countries.4

In the United States, of course, the rule for unpublished papers like these letters is that they are protected by copyright for the lifetime of the letter writers plus 70 years.5

But how do you find out what the law is in another country?

A great resource for copyright law is the World Intellectual Property Organization website. That body, known as WIPO, is “the United Nations agency dedicated to the use of intellectual property (patents, copyright, trademarks, designs, etc.) as a means of stimulating innovation and creativity.”6

On its site, you can find things like a guide to international copyright basics, information on various international copyright treaties, and what’s called WIPO Lex, “a one-stop search facility for national laws and treaties on intellectual property (IP) of WIPO, WTO and UN Members.”7

Using the search mechanism at WIPO Lex, we can find out that Poland has two primary laws on copyright, Law of June 9, 2000 on Amendment to Law on Copyright and Neighbouring Rights and Law No. 83 of February 4, 1994 on Copyright and Neighboring Rights (as last amended on October 21, 2010).8

And using the English-language links provided, we discover that Polish law on these letters is the same as American law: under Article 36 of Law No. 83, the copyright of a Polish author “shall expire after the lapse of seventy years … from the death of the author…”9

Bottom line: Under American law and Polish law, Cynthia can publish any of the letters written by a person who died more than 70 years ago, and any letter written by a person whose permission she can obtain. And with her translator-cousin’s permission, she can publish his translation of those letters as well.

SOURCES

Map Image by Balfour Smith, Duke University

Courtesy Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain

- U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, PDF version at p. 2 (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- See e.g. 17 U.S.C. § 102(a), granting copyright protection to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” ↩

- See Laura N. Gasaway, “Copyright in Translations,” Copyright Corner (Nov. 2004) (http://www.unc.edu/~unclng/copy-corner73.htm : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- “Conflict of laws,” Definition, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University (http://www.law.cornell.edu : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- See Peter B. Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States,” Cornell Copyright Information Center (http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/ : accessed 30 Jul 2013). ↩

- “What is WIPO?,” World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- “WIPO Lex,” World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- WIPO Lex search results, Poland and copyright (http://www.wipo.int/wipolex : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

- “Law No. 83 of February 4, 1994 on Copyright and Neighboring Rights (as last amended on October 21, 2010),” Resources: Poland, World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int : accessed 30 July 2013). ↩

Wow! I knew the issue was a complicated one. Your explanation is so clearly articulated I feel like I have a better handle on the situation. I suspected that the 70 year rule would apply, but I wasn’t positive. I appreciate your explanation and the website resources you’ve listed for reference.

Dziękuję!

You’re welcome, and thank YOU for a great question!

I enjoyed the article because it made me think about the issue. I only wish I had the collection of a set of letters of this type. The topic raises the following questions in my mind. If the collection of letters included letters neither written by the grandmother or to the grandmother, would there be an ownership question even though the letters were in the grandmother’s files? As for letters written to the grandmother, how much proof do you have to have that the letter writer has been dead for more than 70 years? Since the letter writer probably has heirs who are alive, do you have to determine who is the heir and obtain their permission to publish the letters?

There could be an ownership question, though it’s not terribly likely. There’s a reason for that old adage that “possession is nine tenths of the law.” I’d certainly want the same degree of proof for this death that I’d want for any death in my genealogy: the obit, the death certificate, a tombstone photo, just as some examples. And if your ultimate goal is to avoid any copyright questions as to someone who died less than 70 years ago, then, yes, you need to get the permission of the copyright owner, who may be the heir(s)-at-law and it may be whoever was named in any will as the residuary legatee (the person who gets “all the rest and residue” of the estate in the usual language of a will).

My Uncle William Marsh was in the US Navy from 1941 to January 4, 1945 when he died. I have 50-60 letters from William to his mother during that time. Can I put some of them on my blog, or do I after to wait 2 more years?

The question is who owns the copyright, and will that person object, Gus? You should always try to get permission from the person or persons who have the rights. That could be a surviving wife, surviving children, brothers and sisters, etc. If you can’t figure out who owns the rights or the rights owner(s) won’t give permission, then your choices are to use small portions under the concept of fair use or to wait the additional time. And if you decide to wait, it’s not two more years; it’s a little more than that. Copyrights expire on 31 December of the year in question. So a death on 4 January 1945 would leave copyright protection in place for 70 years — 2015 — but would not end until 31 December 2015, not 4 January 2015.

Thanks Judy, William Marsh was never married, both his brother and sister are gone. There is just me and a cousin in South Carolina alive and we both know about these letters. Waiting until December 2015 doesn’t seem that far off.

Gus, if you and the cousin are the only surviving relatives of any kind, chances are pretty good that the two of you agreeing to act would be just fine even now.

This is a very clear summary, but the section on translation raises a question and an issue with me. You write “Just translating a letter for its recipient or for private use without publishing it isn’t a problem and doesn’t require permission.” I am not sure why you think a private translation is not a problem. The derivative work right, of course, is not limited to public expressions (as are the performance and display rights). It seems to me even a private translation technically requires permission. Are you assuming that this is a fair use? Or is it illegal, but no one will know (which is what makes it “not a problem”)?

The issue concerns the copyrightability of the translation if it was made without the permission of the copyright owner. Let’s say the cousin that did the translation did not have permission to do so. Can his infringing work get a copyright? Assuming it does not (and I have a recollection that infringing works cannot be copyrighted), does the translation then enter the public domain so that anyone could use it (so long as they have the permission of the copyright owner of the original letters)? I’ve never been able to figure that one out.

I would consider the translation for the recipient to be as clear a case of fair use as might ever be found, and the translation for private use to be running a pretty close second. And I tend to think that the infringing work can’t be copyrighted but man — that second question of whether it would enter the public domain… hmmmmmm… I can see why you’ve struggled with that one!

If the cousin did not have the permission of the copyright owner, I don’t see how the translation can be copyrighted – which means it must be in the public domain (unless you want to invent a common law copyright in the translation). That means that while it was nice for Cynthia to get permission from her cousin to post the translations, it wasn’t legally necessary.

What really troubles me is the copyright status of any notes the cousin may have made, separate from the pure translation. Does he, for example, have a copyright in his brief bio of Aunt Bertha, even if the rest of the work is an infringing uncopyrightable work? Or does the overall infringing nature of the work taint everything?

I suppose my mind wants to invent an intermediate category between copyright-protected and public domain for an unauthorized translation. Public domain, to me (and to the US Copyright Office), means that you’re legally entitled to use it. Here, there’s something that may not be used by the public in general, but may be used as a matter of fair use by one person. I’m not sure how the law would treat that.