The good, the bad and the ugly

So yesterday was the rollout of the changes in matching systems for folks who’ve had DNA tests at AncestryDNA. And, as usual, there’s good news and bad news in the changes. Enough to warrant breaking with The Legal Genealogist‘s usual Sunday-for-DNA rule to comment today.

Let’s start by remembering what we’re dealing with here. The AncestryDNA test is an autosomal DNA test. It looks at the kind of DNA that you inherit equally from both of your parents: you get 22 autosomes1 (plus one gender-determinative chromosome) from your father and 22 autosomes (plus one gender-determinative chromosome) from your mother, for a total of 23 pairs of chromosomes. So this is a test that works across genders to locate relatives — cousins — from all parts of your family tree.2

Good: Fewer, Better Matches

The good news, of course, is the big change in the matching algorithm that deletes a very large number of people from all of our match lists who really aren’t related to us genetically at all.

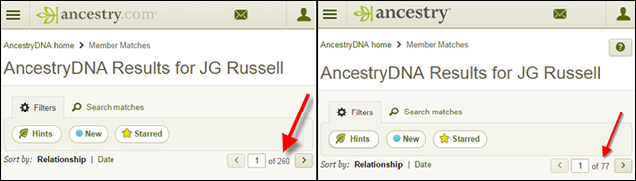

This means that our numbers of matches have gone down — my own results, as you can see here, dropped like a rock: more than two-third of my matches dropped off my list, from roughly 13,000 matches down to about 3,850.

But at the same time, the quality of our matches has gone up.

AncestryDNA’s new matching system begins with a better, deeper, more accurate analysis of the data that helps define who is and who really isn’t genetically related.

One part of the new analysis is through the identification of some parts of our genetic code that really don’t mean anything at all. Some pieces of DNA that we once thought meant we were genetic cousins we now understand just mean we’re all human, or all Scandinavian, or all African. By taking those pieces out of the matching system, AncestryDNA will eliminate many of the false positives.

The other big part of the new analysis is in the way AncestryDNA looks at the bits and pieces of our genetic code that we use for genetic genealogy testing. Since it doesn’t look at all of our DNA, but only parts of it, autosomal DNA testing relies on making some educated guesses about the parts of it the test itself doesn’t look at.

In a way, it’s like reading a book with only some of the words showing up on the page; the analysis system has to guess at what the missing words are. The better the guesses are, the better the results are. So part of the new system is a better way of thinking about what the missing words are likely to be — and in what language. If I’m 100% European, for example, the system shouldn’t conclude that the missing DNA words are in an Asian language.

Emphasizing the right missing words means the people who show up on our lists as matches will be better matches. More accurate. More likely to really be our cousins.

And people we didn’t match before, but who are our real cousins, will show up on our match lists… like a Cottrell cousin of mine who wasn’t on my old list and is on my new one.

Now before people get all bent out of shape about the matches that have disappeared… they haven’t completely disappeared. At least not yet. You can access the old list this way:

1. Go to your DNA Home Page.

2. Under your name, find the word Settings with the gear icon, and click on that.

3. On the right hand side of the settings page, under Actions, there’s a link to “Download v1 DNA Matches” that says we can: “Download a list of your previous “v1″ matching results (available for a limited time).”

We don’t know how long that’ll be there, so if you have earlier matches you want to preserve, download that old match list. It comes in a CSV file format and preserves all of the prior information: if it had a shaky leaf hint, for example, there will be a YES in the HINT column, and if you created a note to yourself about the match, what you noted is reproduced in the NOTE column.

Good and Bad: DNA Circles

The next big change to the matching system is the inclusion of DNA Circles. Think of them as shaky leaf hints on steroids. And they are both good news and bad news all wrapped up in one.

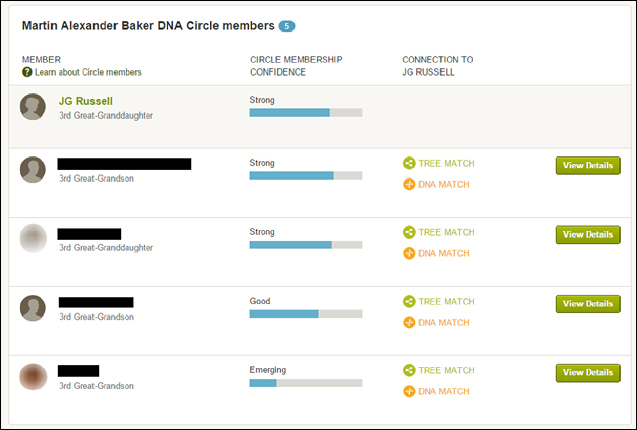

What the circles do is group people who have tested based on their DNA and on their online family trees. Everyone included in a circle will be a DNA match to at least one other person in the circle and everyone in the circle will have a direct line path to some shared person in their family trees. Here, for example, is my DNA Circle for my third great grandfather Martin Baker:

(And please… please, people… respect the privacy of others who have tested. DO NOT go reproducing information without the permission of others who have tested. It’s really easy to black out names and blur photos so you’re not putting information into blog posts or other public places without permission!)

The good part of the DNA Circle grouping is that I don’t have to hunt through every one of my matches to see who else has tested who also lists Martin as an ancestor. This will do it for me. We can now all communicate with each other and share research to see what information one of us might have that the others don’t.

The bad part of the DNA Circle grouping is that not everybody who’s tested with AncestryDNA will show up in your DNA Circles even if you are a DNA match and your trees match. To have this feature at all, you have to be a paying Ancestry subscriber. None of the free accounts will see this. And you have to have a public family tree. Folks with private trees can’t be included.

How deep the family tree data is will affect whether a match lands in a circle too: if the family tree data is fairly complete and the matching algorithm can limit the chances that the match is really in a different line of your family tree, the match is more likely to show up in a circle than if the data is less complete. There’s a lot of information about the circle system and how it works in a white paper that Ancestry subscribers who are in a circle can access (click on the question mark icon when you’re in the DNA Circles area then choose DNA Circles White Paper); at some point, we hope AncestryDNA will make it available to others as well.

And of course it’s still a bad part of this whole thing that we’re forced to deal with someone else’s analysis of what our data really means instead of getting useful tools for comparing the data ourselves.

The Ugly: Misunderstanding DNA Circles

It’s that last point above — that we still have to rely on what someone else is saying about our DNA and our matches — that creates the really ugly part of this change: it’s got a very serious potential to reinforce some very very bad genealogy. And no matter how many times responsible genealogists warn and even AncestryDNA itself warns that DNA Circles do not prove descent from the person identified as the possible common ancestor, people still already believe these circles are proof.

Read through the comments posted yesterday on Facebook and Google+. “I now see who the common ancestor is!” is a common type of comment.

No. No, no, no, no. A thousand times, no.

All we’re seeing is that we are cousins, yes, and that we have somebody that we share in our online family trees. What it does not do is prove that we’re all descended from that person. We could be cousins in an entirely different line — our family tree data could simply be dead wrong.

The whole DNA Circles concept depends in large measure on the accuracy of online Ancestry family trees. And how many times have we all seen major problems with these trees? Someone begins by posting a very complete — but entirely erroneous — line in a family tree, and 10 other people copy it in their own family trees.

Even today, on Ancestry, there are dozens of family trees identifying Samuel Baker and Eleanor Winslow of Massachusetts as the parents of William Baker of Virginia, and Alexander Baker of Boston as Samuel’s father. Um… nope. YDNA testing has definitively disproved that whole notion… but the trees that say it persist and even multiply.

Now if enough descendants get DNA tested and they persist in identifying the wrong people as William’s parents, guess what? We’re going to get a DNA Circle eventually that suggests that they really were William’s parents. And the people who want to believe that they were William’s parents are going to say that the fact that they’re in a DNA Circle with everyone else who claims descent from these same people proves it.

It’s hard enough to convince people to give up cherished notions of common ancestors when the facts don’t support the family stories. But when people are grouped into circles who are in fact related by DNA, getting them to understand that how they’re related may be in an entirely different way, through entirely different ancestors, that the circles are just hints, well… let’s just say I’m not looking forward to this.

Good. Bad. And ugly.

Get used to it.

SOURCES

- “An autosome is any of the numbered chromosomes, as opposed to the sex chromosomes. Humans have 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (the X and Y).” Glossary, Genetics Home Reference, U.S. National Library of Medicine (http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/glossary=Glossary : accessed 19 Nov 2014), “autosome.” ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Autosomal DNA testing,” National Genealogical Society Magazine, October-December 2011, 38-43. ↩

Judy – just out of curiosity – for your wrong Baker circles, does it say that it is an “emerging” circle? or does it show something like “strong”?

Angie, this image of this Baker circle is a correct circle (everyone in it is verified). (We don’t as yet have a “wrong” circle appearing — I used that as an example.) For this circle, three of us are considered strong, one as good and one emerging. No idea why the difference.

Yeah, I’m having a bit of a tough time understanding the emerging, strong, etc. language.

There is some explanation in the help pages, but it doesn’t say exactly how the distinctions are drawn. It mostly focuses on what the distinctions are. My “emerging” cousin appears to have as much in his family tree on the Baker line as I do. So … ?

Each person is given a connection level based on a few things. 1) How many DNA connections a person has in the circle. 2) The confidence scores between individual pairs of matches within the group. 3) The consistency of their tree data and the completeness of their tree.

Which of course raises another issue: name-grabbers with “complete” (even if wrong trees) are getting more weight in the analysis than people who are carefully documenting one line.

It would be interesting to see an informed comment on the generally devastating impact this change has had for people of color, adoptees, etc. Besides losing a known 4th cousin (that I match at other testing sites), I have lost all my distant matches that lent credence to my descent from certain European ancestors. I understand that a shaky leaf is not definitive proof, but five shaky leaves attached to descendants of my theoretical ancestor suggested that I was headed in the right direction. All are gone now, and I’ll never see any others or be included in any of these Circles.

There certainly will be some cases where future matches could be made using better tools, Lisa, and there may well be some hints in our small DNA segments that we’re losing this way. But AncestryDNA isn’t trying to provide tools and guidance for the genetic genealogist who’s trying to make fine distinctions. It’s trying to provide very very broad brush tools for the hobbyist. The rest of us really need to look elsewhere for tools to make those finer analysis decisions — and try to convince our cousins to test with other companies as well.

I will not be recommending this test to my friends or family as long as Ancestry.com continues it’s exclusionary practices. This test excludes almost all people of color whose ancestry was interrupted by the slave trade. The Circles feature doesn’t have anything to do with the science of DNA and won’t tell a match whether they are actually sharing the same lineage at all or which side of their family a match is sharing. This new test removed HIGH matches of mine, not LOW confidence matches at all but HIGH matches who happen to be European cousins that I share large segments of DNA with when compared utilizing the gedmatch chromosome browser tool. These cousins match me on FTDNA as well. Possibly, you are under the delusion that Americans of African descent are not related to you? And therefore do not belong in your matches? But I paid for my test just as you did and I want all of my results! This test actually excludes American descendants of African descent and Native Africans of continental descent who do not share surnames in common because of the upheavals and separations that resulted from slavery. It also excludes almost every person of color and is biased to the benefit of people of European descent who are under the delusion of exclusion!

NONE of the DNA tests, without more analysis, can tell you “whether they are actually sharing the same lineage at all or which side of their family a match is sharing”. Segment data would be helpful, yes, but it must be combined with the paper trail to answer those questions.

If you have a parent tested like I do and the cousin matches that parent then by process of elimination you will KNOW what side the cousin matches you on. Also, if you have tested a paternal Uncle or Grandparent as I have and that cousin also matches that Uncle or Grandparent then you have further analysed where that match falls. I have known family tested from both sides of my family for this purpose.

Sure, testing parents (if they are alive) or grandparents (even better) will get you that information, and testing cousins from specific lines adds a lot of depth. But my point stands: just doing your own DNA test won’t cut the mustard.

Judy,

I like to hope that getting involved with my circles at AncestryDNA will help to assure better accuracy for my ancestor’s and relative’s records. It might be a chance to set things right, where the opportunities so rarely seem to come around. One cousin at a time! Now to get my public tree poised with filling in descendants…

Lisa R.

We all hope that can be the result, Lisa. We just fear that it won’t be…

I can get my known cousins to test at other companies and have. The problem is the unknown cousins who are descended from the 40% of my ancestors who were of European descent. Though I have a relatively high percentage of such ancestry, my most recent white ancestors were two great-great-grandfathers. My mixing started in the colonial era, and the hints to confirm identities lie in my distant matches, some of whom showed up in v1.

I understand the constraints, Lisa, but the very very large number of false positives were more of a problem for most users than the relatively small number of what might now be regarded as false negatives.

I understand that. And for people whose genealogies descend in orderly, documented ranks, free from slavemaster paternity or undocumented marginalized others, this is a win. For the rest of us, not at all. Ancestry has lost what made it most helpful for people like me.

Which is why we need to remember that Ancestry is not the only game in town.

I play in the other games. The only thing Ancestry had going for me was the ability to match a paper trail with distant DNA matches to yield more evidence of suspected ancestry. I realize you don’t work for this company. However, I’m still waiting for some authoritative acknowledgement that this new algorithm slams the door on large groups of Americans. Not just clucking about the “greater good.” It’s clear. Them’s that got shall have, them’s that not shall lose. Privilege wins at Ancestry.

Nope, I sure don’t work for them — and it’s them you need to explain your views to.

As you know, I work with adoptees. This has hurt them even more than not having the data did as it has removed some of the patterns we used for defining family trees. We were right, as DNA tests proved, when we identified the birth family. I lost the three trees with common ancestor shaky leaves that led me to a possible birth family for the woman I am working for now. I would be much further away from solving this case without these hints and as you know, I am a heavy user of all the tools that are available.

Much worse, is that Ancestry is encouraging people to make their trees public. Not only are adoptees’ trees protecting the privacy of people who may not know of NPEs, they are often highly speculative. Ancestry trees have enough strange data in some of them without adding speculative trees into the mix. My adoptees opened their results page yesterday with a personalized message from Ancestry urging them to make their trees public. That is a very bad idea, but I am already seeing people opening these trees so they can see if there are any DNA Circles. Surely Ancestry can come up with a solution that still honors private trees.

In general I liked your blog very much and was glad to see more than just the rosy review. I wanted to make you aware of this situation with private trees.

I do understand the issues, Diane, and I don’t think we’re going to see anything addressing this for the private trees. What we have been told is that we can — for example — make a tree public, give it five or six hours to ensure that all the circles populate, review the information, and then take the tree private again. And, of course, the middle of the night is the best chance to ensure that inadvertent disclosures are avoided as much as possible.

Yes, I have worked with many adoptees in finding their birth families. I do this as a hobby and always free. I build speculative trees that are very helpful. It would be wrong to make these trees public. I just completed a very long search that many others called impossible. The new ancestry rules may have kept it impossible. Sometimes adoptees do not even know the names of their parents. I have purchased a dozen DNA kits and two of them are still unused. I feel betrayed and know I will not get the information from the DNA tests I expected when I purchased them. My aunt is in her 80s and this is the hope we had in possibly finding information about her father. The green lines were helpful in the research but are now meaningless. Only the most difficult searches require DNA and then every clue has its possibilities. I am surprised at my reaction to this. It is causing me to totally rethink all that I am doing. I am trying to figure out how to drop ancestry.

There are pluses and minuses in every change. I know some DNA adoption angels will be making trees public briefly, in the middle of the night, just long enough to let the Circles populate, copy the info, and then take the trees private again.

Lisa, for a limited time, you can download your list of old matches. I would do it asap; not sure how long that feature will be available. Go to where you click to download raw data — there is a button above it, I think for the v1 list.

Judy, Do you have a Battles circle yet? My dad’s kit doesn’t have a circle for Battles, but one of our matches does show as a match. My dad does have 4 kits, which are really two sets of husband/wife so only 2 circles really since all the matches (8 in each) seem to be the same.

Hi, Cynthia. Yes, I’ve done that and am glad for that option. Moreover, I’ve kept notes re my Simonton, Nicholson, Van Pool and Herring shaky leaf matches. Can’t help but rue the lost opportunities going forward though.

Your notes are preserved in the downloaded info as well.

No Battles circle yet, darn it. Sure would like to see one… but I may be a bit far removed personally to see it.

Wonderful overview of the AncestryDNA changes. Thank you!

Glad to help.

I take it back! Two of my circles ARE Battles – Noel Battles is one, the other is his wife. AND, the person I thought was in there doesn’t appear to be. Weird. It looks like only one at this time is a dna match, several of the others appear to belong to one family, so not much of a circle at this point. They are all emerging. My other circle seems to be better dna-wise at this point.

Well, I have actually been put in a DNA circle for the wrong ancestor (and his wife and father!) as proven by Y-DNA. The worst part? When others click on my View Details within the circle, it actually gives my descent from these wrong ancestors. Even more mind-boggling, it says they came from MY TREE, even though I have an entirely different ancestry given! To repeat: Nowhere do the ancestors that I actually put in my tree appear within the circle, thereby reinforcing the wrong information. I hope they find a way to flag actual differences in the trees so people can say, hey, maybe there’s a better option here. Otherwise, I’m sunk.

Oh ouch. That’s exactly the kind of thing that I’m afraid of.

This is the second case I have seen or heard of this happening. I don’t think it’s a simple “erroneous genealogy” issue, I think it’s a programming glitch and that when these occur people need to take a minute to let Ancestry know (although how to do this is a question).

Part of the “good trees, bad trees” issue is mediated by the use of point ancestors, not actually the trees they are in; you can see the path of each tree member to that point ancestor (and you can see their trees)so you do have the possibility of coming upon a wrong path of inheritance to that point ancestor and/or a completely awful tree but it doesn’t negate that all in the tree have a DNA link to that point ancestor although not necessarily to each other.

But the totally different tree issue, without the proper ancestors in it has to be a different problem.

It really does seem like something is wacky.

Just to clarify. Probably 90% or more of my cousins have the wrong ancestor, let’s call him John Wrong, in their trees. So it doesn’t surprise me unduly that we are all flagged first as being related and secondly that the program picks what it believes is the consensus ancestor, John Wrong, his wife Mary Wrong, and his father Bill Wrong.

But that it overrode James and Sarah Probable in my own tree to place me there…and then said it got it from my tree…that’s a big problem. I’ve spent years trying to straighten this out by showing people that we have Probable Y-DNA and not Wrong Y-DNA. Though I’ve obviously failed given how many have the Wrongs in their tree!

At the moment, the only people in John and Mary Wrong’s DNA circle are from my line of James and Sarah Probable so I’m guessing there is no way for the program to get conflicting DNA results to actual descendants of John and Mary Wrong.

BUT, the glimmer of hope here is that John Wrong’s father, Bill, has a large number of STRONG DNA matches between those who are documented descendants of Bill Wrong. I know that because myself and a few others, closely related to me, from James and Sarah Probable are listed in the Bill Wrong circle as WEAK, with absolutely no DNA matches to any of Bill Wrong’s documented descendants.

Do I really think that will change anybody’s view of our connection to Bill Wrong and his son John Wrong, though? Probably not, but at least it makes me feel better.

I did contact Ancestry on the DNA Circle feedback page but only in general terms to say that the program shouldn’t override my own tree WITHIN THE CIRCLE LIST’s VIEW DETAILS where it lists my descent from John Wrong and then states it came from my tree.

BTW, I actually like the circles. (Well, I’d like them much better if they had a share segments option but I’ll take what I can get.) I just don’t want the program to assume that because I may be the only person in the entire circle who has James and Sarah Probable in my tree that I am, haha, Wrong. Instead, it should keep me in the circle (we are all related) but show my alternative ancestry to the Wrongs.

Hope that made sense!

It sure makes sense to me, Mary. It’s rewarding people who just copy the Wrong information and ignoring those who are cautious or even (gasp) carefully document a line. And that’s a BIG problem.

My atDNA is on a free account (I have a library account for most usage). I suppose then that it is not a “public” tree though plenty have found me on it because of the atDNA matches. That being said, there is still a feature much like the “circles” you talk about, and that is there is a way to filter your matches just to those who have family trees. I assume the results it then shows–how we descend from a common ancestor–or pretty much the same thing as what “circles’ is doing.

And THANK YOU for the caveat that just because they show a common ancestor does not mean they are right. However, it is still interesting to see some of the surnames I so rarely work on anymore showing back up with matches–of people I have NEVER heard of.

Yes, there are ways to get more out of the results even if you don’t qualify for Circles. What you don’t get is the “in common with” type of filtering: the circles bring together people with tree matches where the DNA may be person A matching person B matching person C.

“…it’s got a very serious potential to reinforce some very very bad genealogy”

Isn’t that Ancestry’s motto? Haha.

On a serious note, each DNA Circle member comes with a little green button that says “View Details.” How about some matching segment information at the bottom of the page that pops up? Come on, AncestryDNA, give us some ammunition with which we can fight that very very bad genealogy. I bet you’d be surprised at how quickly we’d learn to use that data to enhance the whole experience.

Crista Cowan, are you still there?

I tend to agree with Roberta Estes (“Ancestry’s Better Mousetrap – DNA Circles“) who said we will get the segment data when and if some high-ranking Ancestry person decides he or she needs it. And not until then.

Yes. I’m inclined to agree. But until and unless that day comes, I don’t think I’ll be able to shut up about this.

And we shouldn’t quiet down about this, Jason. Letting the company know what genealogists want is, well, what customers should do!

How timely!! Before going to bed last night, I had called Ancestry help line last night twice, wrote them an email, and wrote suggestions for DNA tools in a survey–all of which are things I rarely do.

The first call was to find out where all the autosomal results went for the other 9 autosomal tests of family members that had previously been prominently displayed on my home page. (I didn’t notice the new drop-down on my home page labeled “Other Tests.”)

The 2nd call was to find out where all the Y-DNA matches (or near matches) went for

elderly uncle, the last known White family descendant, my biggest brick wall. You told us Ancestry was discontinuing support for this test, but I didn’t expect results to be deleted. I’m so angry about that! The help desk response was to contact Ancestry.com via email. (Funny, I didn’t get asked to do a survey at the end of that call.)

Lastly, when asked to fill out an online survey, I asked for a tool so I could see in a table format common matches among all the DNA tests I paid for. For instance, if I see that my cousin Susan and I share a match, then I can focus on the Scandinavian side of the tree. I also asked for a better member search. Finally, I suggested that if they can’t provide the tools, could they at least provide the ability to download the matches for each test so I can use Excel to see patterns. I was so pleased when you gave the instructions to download the V1 files.

Now that I have downloaded all the V1 files, I’m going to assign each person a color and highlight the contents of each file accordingly. While it is highlighted, I’ll filter out the 5th-8th cousins (select all=>Data=>Filter; then unclick 5th-8th). Next, I’m going to cut and paste all ten files into one big Excel worksheet and sort by name. The common matches will appear together and the color will tell me what relatives match this name. With this list, I should be able to do a more targeted investigation.

Again, thank you so much for this tip and for your always informative, entertaining blog. You’re the best!

Glad to help… and want to advise you that we may have some luck down the road in retrieving the YDNA results. No promises, but we have some hopes that Ancestry is listening on that.

My DNA results: “Currently, you aren’t in any DNA Circles.”

I never win the lottery either.

Maybe down the road, Doug — and make sure your tree is public (and nag your matches!).

Judy,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2014/11/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-november-21.html

Have a wonderful weekend!

Thanks so much, Jana!

I also lost a fairly close known relative from my matches that showed up before. It makes me wonder how many unknown relatives were lost.

There is no doubt that there will be some loss — call them “false negatives.” I think they’re outweighed by the false negatives of the former “include everything” approach.

Paper trails have always had a bias, which has not helped minority groups, women, children from NPE, and even those whose whose records were destroyed. Many of us have looked to genetic genealogy to help to reverse the damage done by the built in prejudices of the past. This doesn’t just hurt the minority groups or women, it hurts all of us. We need to be actively seeking the best methods to bring forth the truth from the past that is inclusive.I am not talking about revisionism but certainly fair access to all records. I was encouraged to join a heritage group that was closed to minorities and I chose not to even though it meant I was denied access to documents, etc. I am happy to say that heritage group changed and became more open, transparent and inclusive. The bias has been built in but how we move forward is where it is time for this to be handled differently. I have a Native American relative that is one of my closest matches and I embrace this although other “cousins” do not seem to. Maybe his family will hold the key to a health issue in my own children. I need him in my tree AND the cousins who do not seem to embrace him. We don’t chose our family. I will have to review this but it looks like they are not listing his line in their tree. I am not saying throw out the paper trail but is fair and equal access to both the paper trail and potential match information really too much to ask for in this day and age.I hope ancestry will work to be transparent and inclusive. I certainly hope this will be what we see going forward.

We need everyone in our DNA trees and our family trees who belongs there, Susan. It’s figuring out if each person really does belong there, on the basis of real evidence rather than wishful thinking, that’s the hard part. There are some who will bitterly fight “losing” links to Native Americans who really truly are not relatives — because they want to be NA. And there are some who will bitterly fight having a link to Native Americans who really truly are relatives — because they don’t want to have NA relatives. All we can do is accept that the chips fall where the chips fall.

I am not Native American. We are not related through the Native American side. We are related through a different line. The man is a leader in the Native American community and he believes we are related. He actually has a good paper trail for his Native American side. This is NOT an example of me wanting to be Native American. This is an example of me including a family member that some cousins seem to be excluding. But more to the point, others in this thread have already expressed concerns on similar issues. This is a question of fair access to all documents and match information.

I’m not suggesting this is your attitude, Susan, only that this sort of “wanna be” or “don’t wanna be” element is also a real concern.

Yes, I agree. My response is that the wanna be element is best addressed by fair access and transparency in regard to documents and match information. Thank you.

Well I get really disappointed when your reading it tells you that you have a high degree of a DNA Match like 3-4th cousin and you check them out only to see that you can’t see because they aren’t sharing, so that makes it harder to continue.

I certainly agree that it gets very frustrating when someone doesn’t have any information posted and doesn’t respond to inquiries.

Hi, I’m late to this post but I’ve just come back to ancestry after a few months away and found that some of my closest and most likely real matches are gone. My question is, some of those matches are uploaded at GEDmatch and they are some of my closest matches there as well. Does this mean that the GEDmatch results are wrong and like ancestry says, they are “false positives” or is the raw data reliable, and it’s ancestry that changed only how they interpret it, therefore making them “false negatives”? I was getting close to a breakthrough on a brick wall when this happened and now I can’t tell if I was on the right track or not. I’m inclined to trust the raw data at GEDmatch, but I just don’t know. Thanks!

I can only give a great bit “it depends” answer. Any segment that is bigger than about 10-11 cM is very very likely to represent a shared inheritance than mere chance. Any segment smaller than that is a crap shoot.

Great, thank you. These are all matches around 30+ cm, which is why I’m surprised they disappeared. I’m going to download my v1 matches for safekeeping. Thanks for info on how to do that!

Just be aware that there’s a difference between total shared DNA of 30+ cM and one segment being that long. The former could be a false positive, the latter would be rare.

Yes these are all one segment matches. That’s why I was surprised when they disappeared from ancestry. Thanks!