Ohio’s unique rule

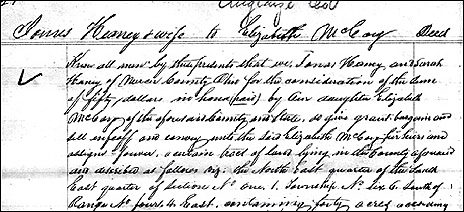

The deed itself is in the usual form: a fee simple transfer of 40 acres of land from Jonas and Sarah Haney of what was then Mercer County, Ohio, and later became Auglaize County, to Elizabeth McCoy of the same county.

The 1840 document contains the usual land description, recital of the payment, and warranties of title.

The 1840 document contains the usual land description, recital of the payment, and warranties of title.

And the wife in the transaction, Sarah Haney, “in consideration of the the sum of one dollar … in hand paid” gave up her dower rights to the land as well.1

None of which gave reader Pam Vestal any pause at all.

What bothered Pam was the fact that, by this deed — and another one executed around the same time — Jonas and Sarah were transferring land to two daughters.

Not sons.

Not sons-in-law.

But daughters. Married daughters, like Elizabeth (Haney) McCoy. At a time when married women had very few rights over their own property.

Why, she wondered, would the parents do this? Didn’t the land automatically get placed under the control of their husbands? What advantage could there be to giving it only to the daughters?

Pam is surely right about the rules affecting married women and control of property like this. Under the English common law, as followed in most of early America, a wife had no separate legal identity from her husband:

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing; and is therefore called in our law-french a feme-covert; is said to be covertbaron, or under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord; and her condition during her marriage is called her coverture.2

And, under the common law rules, “all deeds executed, and acts done, by her, during her coverture, are void, or at least voidable…”3

Under the common law, a husband was given ownership of all of his wife’s personal property, and control over all of her real property — her land.4

The laws didn’t start changing in the United States until the 1830s — Mississippi was the very first state to enact a married women’s property act5 — and Ohio didn’t pass its first statute giving a married woman some control of her real property until 1861. And that law only protected women whose husbands no longer lived with them.6

So why in the world were the Haneys selling land to their married daughters?

It may have been because the Ohio Supreme Court had spoken on the issue — and had done something no other court until then had done. The Ohio Supreme Court had recognized the right of a married woman to dispose of her property — even her real property — by writing a will.

In 1831, the Ohio Supreme Court was called upon to decide a contest over some land. It had been owned by one Catherine Pegg, a married woman who was separated from her husband and who alone lived in Ohio. She had left the land in her will to her daughter Mary Ann Pegg, who had sold it in 1830. The question was whether the will was valid, or whether the husband — still living — had rights in the land since he hadn’t consented to the will.7

The Court began by noting that common law certainly did not allow any married woman to make a valid will.8 But, it went on, the issue turned not on common law rules but on Ohio statute, and:

On February 18, 1808, (a) law was enacted to take effect on the first day of June of that year. 6 Ohio L. 75. The first section points out who may make a will. It enacts as follows: “Every male person aged twenty-one years or upward, and every female person aged eighteen years and upward, being of sound mind, shall have power, at his or her will or pleasure, by last will and testament, in writing, to devise all the estates, right, title, and interest in possession, reversion, or remainder, which he or she hath, or at the time of his or her death shall have, of, in, or to lands, tenements, hereditaments,” etc. Upon these general words and expressions there is no restraining clause, nothing from which we can infer that the legislature intended anything more or less than is expressed. … What, then, is the meaning of the words “every female person?” Is not a married woman a person? She is, so far that she may be punished for her criminal acts, and why may she not be, so far as to make a will? She labors, it is true, under many disabilities, but it is within the power of the legislature to remove those disabilities, and when this power is exercised, it is not the province of this court to correct the procedure. If a married woman is a “female person,” she is authorized by the act of 1808 to make a will, and that she is thus authorized, seems to be clear beyond a doubt, to a majority of the court.9

It added that, “By the act of February 10, 1810, 8 Ohio Stat. 146, the testator is authorized ‘to devise all the estate, right, title, interest in possession, reversion, or remainder which he or she hath, or at the time of his or her death shall have, in or to lands, tenements, etc.’ This was the statute in force at the time Catherine Pegg made her will, and at the time of her decease. No one will deny that a married woman hath an interest in her own land.”10

So, the Court held, “by the statutes of February 10, 1810, a married woman had an unquestionable right to make a will.”11

By deeding the land to their daughters alone, then, Jonas and Sarah gave them a power few women in America had at that time: the right to decide to whom the land would go after their deaths. Their husbands would have had the right to control the property during the marriages, yes, but they didn’t own the land, couldn’t sell the land without their wives’ consent — and couldn’t control where the land would go after their wives’ deaths.12

Land for Ohio’s daughters. And a first step towards women’s rights.

SOURCES

- Auglaize County, Ohio, Deed Book 1: 27, Haney to McCoy, 28 March 1840; Auglaize County courthouse, Wapakoneta; FHL microfilm 914113. ↩

- William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book I: The Rights of Persons (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1765), 430; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 Sep 2015). ↩

- Ibid., 432. ↩

- James Kent, Commentaries on American Law, 13th ed. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1884), 2: 130. ↩

- §22-26, Chapter 31, “Husband and Wife,” in V.E. Howard and A. Hutchinson, compilers, Statutes of the State of Mississippi (New Orleans: E. Johns & Co., 1840), 332; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 Sep 2015). ↩

- “An Act concerning the rights and liabilities of married women,” Ohio Laws of 1861, chapter 71, in J.R. Sayler, editor, The Statutes of the State of Ohio…, 4 vols. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1876), I: 63-66; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 Sep 2015). See also “First Women’s Rights Movement,” Ohio History Central (http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/ : accessed 7 Sep 2015). ↩

- Allen v. Little, 5 Ohio 66 (1831). ↩

- Ibid. at 67. ↩

- Ibid. at 70-71. ↩

- Ibid. at 68. ↩

- Ibid. at 72. ↩

- They may well have had curtesy rights — a life estate in the lands — if they survived their wives and their wives had borne them children. See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 311, “curtesy.” But they wouldn’t have owned the land. ↩

Wow, wow, wow! This information couldn’t have come at a better time! I was literally just questioning this exact same thing last week about an Ohio will! Thanks Judy!

You can thank Pam for asking the question at the right time!

This caught my eye because I have deep roots in Auglaize County Ohio!

I have to wonder WHEN the deed was recorded though – if it was in Auglaize County, it couldn’t have been recorded until AFTER 1848, since the county didn’t exist before that.

Which brings up wondering why people delayed recording deeds – I have some deeds that were originally signed in the early 1870s, but not recorded until after 1880. Wouldn’t you think people would want others to know who owned the property?

Two points: (1) when Auglaize was formed, deeds from its parent county were re-recorded in the new county (a common occurrence to ensure that title to land in the new county was clear in the new county), but the original deed was at least acknowledged in what was then Mercer County in March 1840; and (2) the main purpose of recording a deed is to prove title, and if you had the deed, you could prove it any time. So recordation wasn’t all that important until we started to regard it as a way of giving people notice.

Very interesting and I followed you until the next to the last sentence, to wit, “Their husbands would have had the right to control the property during the marriages, yes, but they didn’t own the land, couldn’t sell the land without their wives’ consent — and couldn’t control where the land would go after their wives’ deaths.” The law clearly granted all women, aged 18 and up, the right to dispose of their property via a will. But it is not clear at all to me how the husband could legally control the land during the marriage but be precluded from selling it during his wife’s lifetime without her permission. It seems to me, either it’s hers and she alone controls it or it’s theirs and he alone controls it by the coverture part of common law. The law doesn’t seem to address any aspect other than the right to devise property by a will. What did I miss? Was the husband’s degree of control DURING her lifetime restricted depending on whether the wife had written a will?

Thanks!

Skip

What’s missing is clarity on my part that control isn’t necessarily the same thing as ownership. His right to control the land generally didn’t extend to a right to sell it unless she also signed off. As early as 1771, for example, New York law required a married man to have his wife sign any deed for her land and required that she meet privately with a judge to confirm the sale. She could own the land, but couldn’t sell it or enter into any kind of contract about the land without his joining in. Her husband had the right to the rents, the profits, to say if it was planted or left fallow. The land could often be taken to satisfy his debts.

Got it. Thanks, Judy!

Thanks for the nudge to explain better!

My ancestor relocated from Pennsylvania to Ohio in 1820. At that time, he recorded the deed to his Pennsylvania farm by which he had purchased it in 1805, as well as the deed by which he sold it. One of the items in both deeds is the mention that Catherine, wife of the 1805 seller, and Judith, wife of Peter, were taken and examined separately at the courthouse and gave their consent to the sales.

The wives would be invited to a private office and have their dower rights explained / reviewed without their husbands present, and gave their consent privately. In this case, the only record of Peter and Judith’s marriage I have yet found is this deed, since if they weren’t married, her consent wouldn’t be required. [Their oldest daughter was born in New Jersey in 1791, but they aren’t in NEW JERSEY MARRIAGES. Still hunting.]

When the land being sold belonged to the husband, then what the wife was consenting to was the disposition of her dower rights in the land. In some cases, the land itself was hers — and only some states required that she be separately examined in either case.

I seem to recall hearing that VA land records usually had the wife sign but in NC that was not the custom. Finding the seller’s wife signing a NC deed is considered an indicator that the buyers were from VA. Buyers from VA thought the NC sellers were up to something and insisted the seller’s wife sign. Am I remembering that correctly?

J. Mark Lowe so instructs, and in my experience it’s often been the case. On the other hand, I’ve also seen people born and bred in NC do the same.

I believe the Sayres mentioned it in the Advanced Land class at GRIP.

Thank you!

It wouldn’t surprise me to have heard it there too! It’s one of those things you hear repeatedly — but again I caution that I have seen people born and bred in NC on both sides of a land deal and having dower rights expressly waived anyway. Sometimes the issue was what the clerk wanted before recording the deed rather than what the grantor or grantee might have thought was needed.

Hi Judy,

Interesting post that perhaps solves something I tried to investigate at one of the Massachusetts Law Libraries. When one of my male ancestors died first in Ohio, the detailed inventory included a list of the property that my female ancestor had brought to the marriage, with the implication that it was excluded from the value of my male ancestor’s estate. I was able to quickly determine at the library that by the time he died women could own property. However they had married in 1834 and it remained unclear to me as to how she had been legally entitled to keep the property she’d brought with her at the time. (I should note that this wasn’t real estate, but items like furniture.)

THANKS! This topic is my “obsession du jour.” I’m trying to trace 200 acres in central Kentucky that appear to have been passed down from a Rev. War patriot to his wife, then circa 1824 to their daughter. DAR is questioning that daughter’s right to own land, yet I have a court record dated 1851 in which one of her adult sons returns home to sell his share of land “inherited from his mother.” (The mother died in 1833. His father has been paying taxes on this land since the mother’s death. This son is selling his one-third share to his brother and brother-in-law, but those relationships are not defined in the document.) One professional researcher says maybe this ownership was a “family understanding” never committed to writing. I’m finding no deeds, land transfers, wills, or settlements that will nail this down. A DAR supplemental is riding (in part) on proving this chain of ownership! Any ideas?

DAR is questioning the right of the daughter to OWN land??? Are they kidding? If they will look at the Kentucky Digest of 1822, they will see that where there wasn’t a will (and you’re saying there isn’t one), the law of descent at that time was to the children — male and female — in equal shares. Daughters would inherit, as well as sons. Period. The husband of any married daughter might control her land, but she would own it.

BEAUTIFUL! This information is a huge help. Thank you, Judy G. Russell. With your info plus other findings, I’m now ready to begin writing my analysis.

Judy,

I want to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2015/09/follow-friday-fab-finds-for-september.html

Have a wonderful weekend!

Thanks so much, Jana!

My great great grandfather, Samuel Atherton, came to Ohio round about 1836. His wife followed two years later. Sarah was his third wife and all the land purchased after her arrival was in her name. The story came down that the land was in her name so that their son, George, who was about 16 years younger than the youngest son from the second wife, would be the only inheritor. No will was ever found for either Samuel or Sarah. That strategy seems to have worked. The parcels purchased in her name are still in the family.

Thanks Judy, love your blog.

Make sure you look for a possible prenuptial agreement — not unusual in a second or later marriage!