Sometimes legal lingo is another language altogether

In a comment to Friday’s post about legislative petitions, reader Barbara Schenck asked about a petition her ancestor Seth Hazel might have filed that resulted in an 1856 Texas statute authorizing a land grant. That statute, “An Act for the relief of Seth Hazel,” authorized the Commissioner of the General Land Office “to issue to Seth Hazel a certificate for one league and one labor of land.”1

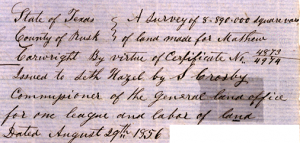

And one of the land surveys for the ultimate owner of that grant, Matthew Cartwright, covered 8,890,000 square varas.2Say what? League? Labor? Vara? Ah, the language of the law… and the land… in the Lone Star State.

Understanding legal documents from Texas and other jurisdictions that were once under Spanish influence requires an understanding of the terms used.

League, labor, vara — these are old Spanish units of measurement that persisted well into the 19th century, and can even be found in modern land records in Texas.

The smallest measure here was the vara. The term comes from the Latin and eventually came to be used to refer to the lance, or badge of office, of judges and mayors. When those started to be standard lengths, it began to be used as a unit of measurement, roughly 33 and 1/3 inches, and a million square varas equalled a labor.3 Be aware that the vara was used in other jurisdictions and can be slightly different there. In New Mexico, for example, it was 33 inches; in Florida, 33.372 inches.4

A labor isn’t pronounced the way the English word is. Remember, it’s Spanish and it’s pronounced lah-bór. Again, it’s a unit of measurement, equivalent to 177 acres. And it had a particular meaning: it was farm land, land intended to be used for agriculture.5 A casa de labor is a farmhouse.6

A league in this specific context is another Spanish unit of measurement. I have to emphasize “in this specific context” because the word was used so many different ways throughout the world7 and even just in North America.8 When it came to Texas land, the league was also called a sitio, “a tract for raising horses, mules, and cattle … the equivalent of 4,338 acres.”9 The league was 5,000 varas square, or 25 million varas.10

So why were so many Texas land grants — like the one to Seth Hazel — for one league and one labor? Because new settlers were very much wanted in Mexican Texas, and they wanted both grazing land and farmland, heads of families were entitled under the Mexican colonization law of 24 March 1825 to both: one league and one labor.11

A nice little history lesson? Maybe. But don’t be so fast to consign these measures to the past. The Texas vara was legally defined as 33-1/3 inches as late as 1919,12 and you’ll find all of these terms used even in modern deeds and court records.13

And anybody tracing ownership of this land back to the original grant will need to know just what it was that Seth Hazel was entitled to and what ultimately ended up in the hands of Matthew Cartwright — one league (4,338 acres of grazing land) and one labor (177 acres of farmland).

SOURCES

- Act of 29 August 1856, in H.P.N. Gammel’s The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897, 10 vols., (Austin : Gammell Book Co., 1898), 4:716; digital images, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History (http://texashistory.unt.edu : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- Land Grant File No. 102, Rusk County, Texas, Matthew Cartwright patentee, Seth Hazel grantee; Texas General Land Office, Austin; digital images, Texas General Land Office (http://www.glo.texas.gov/ : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- Texas State Historical Association, Handbook of Texas Online, “Vara,” (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- W.C. Wattles, “The Variable Vara,” Surveying and Mapping: Journal of the American American Congress on Surveying and Mapping, 10: 198 (1980) reprinted online at (http://888surpass.com/vara.pdf : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- Handbook of Texas Online, “Labor (Land Unit).” ↩

- See Google Translate, “casa de labor” (http://translate.google.com/#auto|en|casa%20de%20labor : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), League (unit),” rev. 9 Feb 2012. ↩

- Roland Chardon, “The Linear League in North America,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 70 (June 1980): 129-153. ↩

- Handbook of Texas Online, “Sitio.” ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), League (unit).” ↩

- Handbook of Texas Online, “Land Grants.” ↩

- Laws of 1919, chapter 130, sec. 1, in H.P.N. Gammel’s The Laws of Texas (1919), supp. vol. 19: 232; digital images, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History (http://texashistory.unt.edu : accessed 12 Feb 2012). ↩

- See for example Tex. Parks & Wildlife Dept. v. Sawyer Trust, 354 S.W.3d 384 n.17 (Tex. 2011) (Hecht, J., concurring and dissenting). ↩

Judy, was this just for Texas? Or would one find similar Spanish terms for land grants etc. in other southern states which were once under Spanish jurisdiction? Fascinating information, I must say!

You absolutely will see some of these terms elsewhere under Spanish jurisdiction, Celia. As noted, the vara was used (but defined as a slightly different measure) in New Mexico and Florida. So yep — you need to know ’em.

Ah, Judy, thank you for taking Seth under your wing. He has made my genealogical life interesting, to say the least. Just this morning I translated seven pages of Spanish about his entitlement to land back in 1835. Then he was applying for land on the Red River.

I’m wondering now if he had selective amnesia about this grant, because when he applied for the one that ended up with Matthew Cartwright, he said he hadn’t received any earlier grant, as I recall. And then there’s the grant in Jack county, too. Matthew Cartwright got that land as well. Hmmm.

I’m glad you mentioned varas because I was going to email you this morning and say, “Don’t forget the varas!”

Don’t eliminate the possibility that he may have been entitled to two grants (one as a resident, one for service) and don’t overlook the fact that the statute said he could have this grant but had to turn back in some other claim!

Yes, I’ll be looking at all his land transactions closely. And trying to figure out the legal ramifications of them and what he thought he was doing when he did them (like I said, he’s a full time job).