Who gets the kids?

Reader Margie Beldin’s perplexing probate petition problem had a couple more puzzling prongs,1 one of which had to do with the youngest members of her McHugh household.

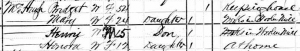

You’ll recall that Frank McHugh died in Pittsfield, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, in 1879; probate on his estate didn’t start until 1888.But according to the 1880 census, Frank left not only his widow Bridget but also children, two of whom were were still underage. Of the three McHugh children living at home with their mother in 1880, Henry was only 15 years old, and Honora (called Nora and sometimes spelled Honnora or Hannora) was only 12.2

So, Margie wondered, wouldn’t there be guardianship records for the children?

Short answer: nope. And, in this case, it’s very much because the estate wasn’t probated until 1888-1889.

Here’s the scoop:

The only time the legal system really cared about kids until very modern times was when they were a public nuisance or a public charge, in which case they were locked up or bound out, or when they were entitled to get property, in which case the law stepped in to make sure the kids didn’t trade the property for a hunting dog and no adult stole it from them.

At common law, there were three essential types of guardians: the guardian by nature; the guardian for nurture; and the guardian in socage. The guardian by nature or guardian for nurture had the right to physical custody of a minor child. That was always the father or, if the father died without naming a guardian in his will, then the mother.3 The difference between the two was that the guardianship by nature lasted to age 21 and gave the guardian control over the child’s personal property. Guardianship for nurture lasted to age 14 and didn’t involve property at all.4 The guardian in socage was the one who had custody of a minor’s lands and person.5

In America, the guardian in socage gave way to the guardian by statute — the person “appointed for a child by the deed or last will of the father, and who has the custody both of his person and estate until the attainment of full age.”6 And if nobody was named by the father, the court stepped in with a guardian by appointment of the court, with the same authority.7

Notice that this type of guardianship came into play only when there was an estate involved. If Papa died, and there wasn’t any property involved, then if Mama was able to keep the kids, she simply kept them. If Mama died too, then Gramma or Grampa took them in. Or Aunt Fanny and Uncle Bert. Or a cousin down the road. Or even a neighbor down the road. This was informal, and if the kids got raised, didn’t starve and didn’t run wild, nobody took a second look. Remember: the notion of formal adoption under the law didn’t even start in the United States until the 1850s. 8

Only if there wasn’t anybody willing and able to take the kids did the legal system get involved. That’s when you find orphans being bound out, or handed over to some respectable citizen to be taught a trade.9

But aha! you say. Frank did have property and he didn’t have a will, so his children would have been entitled to share in his property under Massachusetts law.10 So the minor children Henry and Nora should have had a guardian appointed.

Yup. But somebody had to tell the Probate Court about it. And nobody did. Nobody needed to. The kids were fed, Henry and an older sister worked in a mill, Nora went to school. Life continued after Frank’s death and nobody saw any reason to get the courts involved. Bridget didn’t even start the probate process until 188811 and she didn’t get a widow’s allowance until September 1889.12

By 1888, when the probate process began, Henry was of age.13 And by 1889, even Nora was 21.14 No guardian needed for either of them at that point.

And the moral of this story is:

Just because there should be records doesn’t mean there will be.

Darn it.

SOURCES

- Okay, so I’m on an alliteration kick. Sue me. ↩

- 1880 U.S. census, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, Pittsfield, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 56, p. 343-D (stamped), 32 (penned), dwelling 243, family 319, Henry and Honora McHugh in Bridget McHugh household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 29 Feb 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication T9, roll 531; imaged from FHL microfilm 1,254,521. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 552-553, “guardian by nature.” Ibid., 553, “guardian for nuture.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 553, “guardian in socage.” ↩

- Ibid., “guardian by statute.” ↩

- Ibid., 552, “guardian by appointment of the court.” ↩

- See “Timeline,” The Adoption History Project (http://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/index.html : accessed 29 Feb 2012). ↩

- See e.g. Victor T. Jones, Jr., abstractor, “Apprentice Bonds of Craven County, N.C.: Bonds Dated 1740s to 1760s,” New Bern-Craven County Public Library (http://newbern.cpclib.org/research/apprentice/index.html : accessed 29 Feb 2012).) ↩

- Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the Year 1876, chap. 220, sec. 1 (Boston : Wright & Potter, State Printers, 1876), 217; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 29 Feb 2012). ↩

- Berkshire County, Massachusetts, Probate Court Records 149:216, petition for administration, estate of Frank McHugh, 1888; County Courthouse, Pittsfield; FHL microfilm 1,750,283 item 2. ↩

- Berkshire Co. Probate Court Records 129:64, order granting allowance, 5 Sep 1889; FHL microfilm 1,750,456 item 3. ↩

- He was shown as born March 1864 on the 1900 census. 1900 U.S. census, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, Williamstown, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 89, sheet 1-B (penned), p. 314-B (stamped), dwelling 22, family 27, Henry McCue, servant, in household of Thomas McMahan; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 29 Feb 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication T623, roll 633; imaged from FHL microfilm 1,240,633. ↩

- She was shown as born August 1867 on the 1900 census. 1900 U.S. census, Berkshire Co., Mass., Pittsfield Ward 6, pop. sched., ED 74, sheet 11-B (penned), p. 138-B (stamped), dwell. 188, fam. 216, Nora Forgea. She died 24 October 1912, and her age at death was recorded as 45 (year of birth 1867). Commonwealth of Massachusetts, death certif. no 358 (stamped), Nora (McHugh) Forgea (1912); digital images, FamilySearch (http://www.familysearch.org : accessed 29 Feb 2012); citing Massachusetts State Archives, “Deaths, 1841-1971,” Massachusetts Division of Vital Statistics, State House, Boston. ↩

Another excellent post – I learn so much from your analytical posts like this.

Thanks.

Thanks, Randy! Sure appreciate the kind words.

Amen – what Randy said! Makes so much sense about a few of my ancestors’ children and where they went… and why there were several cousins brought up with a family in the very early 1800s. Thanks again, Judy.

Remember that while we today think of kids as a responsibility and expensive to raise, kids in the past were an economic asset: hands for the farm, workers for the mills. And what we use as a slogan (“it takes a village to raise a child”) was the truth back then: the extended families and neighbors did all raise the kids!

Thanks, Judy. I had been told somewhere along the line there would be no guardianship papers but your explanation clarifies why. Your sourcing is great!

Also, I love the expression “It takes a village to raise a child” and yes, it happened more in years gone by, but not always.

Nora’s daughters, my grandmother and great aunt, ended up in Brightside Orphanage, outside Holyoke, on Christmas eve, just three months after their mother’s death even though she had two siblings still alive and Gilbert had a sister nearby; his father had also remarried and there were many many cousins living in the area as well as other extended family.

Again, I still believe because Gilbert, of French-Canadian descent, married Nora, of Irish descent, bigotry played a big role in their lives.

Thanks, Judy. I had been told somewhere along the line there would be no guardianship papers but your explanation clarifies why. Your sourcing is great!

Also, I love the expression “It takes a village to raise a child” and yes, it happened more in years gone by, but not always.

Nora’s daughters, my grandmother and great aunt, ended up in Brightside Orphanage, Holyoke, on Christmas eve, just three months after their mother’s death even though she had two siblings still alive and Gilbert had a sister nearby; his father had also remarried and there were many many cousins living in the area as well as other extended family.

Again, I still believe because Gilbert, of French-Canadian descent, married Nora, of Irish descent, bigotry played a big role in their lives.

It’s so very sad that nobody in the family would take those children, especially on Christmas Eve! You have to wonder about bigotry, for sure, but also about economics. Nora died in 1912 — and the economic situation of her siblings then may have been so different from the situation when her father died. That’d be worth exploring as well.

I have one case where the mother died and the father was appointed guardian of the minor children. Have always wondered about WHY but now I am going to check to see if those children stood to possibly inherit something from their maternal grandfather. There had to be a reason! I’m really enjoying your posts.

Thanks, Nan! And when you’re looking at that, consider as well that many women did have what was called a separate estate (property owned prior to marriage that equity treated as hers and hers alone) which would go to her children as well, so definitely look at her estate records too.

Thank you for this particular post. I am trying to sort out the details and circumstances of the guardianship of my husbands great-grand uncle which has to this point been more than a little confusing. But your information sheds a lot of light on what might have been going on.

The story of Margie’s family being sent to the orphanage struck a nerve for me. My paternal grandmother once told my Mom that she and her sisters were placed in an orphanage in Vermont when they were small children (early 1900’s). I eventually found that my great-grandfather Victor Potvin had deserted the family and even though there was family on both sides who might have helped them out his wife Virginia was forced to give up her children for a time. The family was reunited by the 1910 census and in 1917 Virginia’s divorce was approved. Pretty scandalous considering they were Catholic but she did what she had to do.

Glad I could help, Pat. Sad story about your grandmother and her sisters. You have to have a steel heart not to agonize for those kids — and their mother.

The Dutch in New Amsterdam used a system similar to what was used in The Netherlands. It was, I think, more pro-active than the above seems to be. It is described in: Adriana E. van Zwieten, “The Orphan Chamber of New Amsterdam,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d series, Vol. LIII, No. 2 (April 1996), pp. 319-340.

Thanks for the reference, Howard!

This was a short-and-sweet description of one potential guardianship situation. You list possible persons who might rear children if a surviving parent were unable, or dead.

Another circumstance I have encountered pretty often is that if one parent died and the survivor remarried, children by the earlier marriage were often “farmed out” (an interesting phrase which originally had a literal meaning).

One context we should all be aware of is that Godparents might step in. In some communities this was an implicit promise by the baptismal sponsors, who were usually relatives of one or both parents, and were often betrothed or married to each other. This is one reason why the full record of baptismal proceedings is extremely useful. The series of abstracts of mainly PA church records that has been published in the last 15 years or so is quite faulty because it omits all baptismal sponsorships — nearly half of the genealogical information therein.

I look forward to seeing more of your lucid accounts in this vein.

Very useful additions here, Jade. The extended records of these families can be extremely helpful whenever they exist and going back to the originals to get them is absolutely the right thing to do.

I have a case where the father left his property to his wife in his will that was proven in 1775 in Kentucky. Later in 1792, a guardian was appointed for this dead man’s young son. I thought that meant that the boy’s mother had died. But someone told me that back in those times, they would appoint guardians when the mother was still alive and I couldn’t assume she died. I am confused. Thanks in advance for helping me.

Pat, I’m a little confused too. We have two issues here. The easy one is that your informant is right. A child was considered an orphan then if the father died, even if the mother was still alive, and if property was involved, the court would appoint a guardian for the child (and that was rarely, if ever, a woman).

But you have a will proved in 1775, and the guardian wasn’t appointed until 1792? The boy would have to have been pushing 17 years old at a minimum at that point, and that’s assuming he was born after the death of his father. That’s still young enough that a guardian might have been required, but it sure raises the question of what happened in 1792 that a guardian was necessary then and only then.