It’s about time for an Arkansas divorce

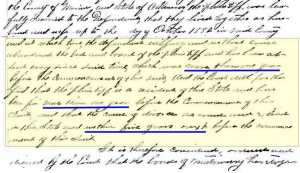

Reader Jo Arnspiger ran into some language in Arkansas divorce complaints from the 1880s that left her scratching her head. Every document she came across had the same sort of language involving three time frames:• first, that one party to the marriage had abandoned the other “more than one year before the commencement” of the divorce action;

• second, that the person seeking the divorce was a resident “for more than one year” before the suit was filed; and

• third, that “the cause of divorce occurred and existed in this State and within five years next” before the suit was filed.

What, she wondered, were those time periods all about?

Each of those time frames was critical to the power of the Arkansas courts to grant a divorce, and that’s why each one will be set out in pretty much the same boilerplate-type language in every divorce complaint or court order granting a divorce during that time.

Arkansas in the 1880s was one of the more liberal states when it came to divorce law. Among the grounds for absolute divorce at that time were:

• (1) impotence;

• (2) willful desertion “for the space of one year without reasonable cause;”

• (3) existence of a prior valid marriage;

• (4) conviction of a felony “or other infamous crime;”

• (5) habitual drunkenness for a year;

• (6) “such cruel and barbarous treatment as to endanger the life of the other;”

• (7) “such indignities to the person of the other” as to “render his or her condition intolerable;”

• (8) adultery after the marriage; and

• (9) permanent or incurable insanity after the marriage.1

That second ground — the one-year period for desertion — was among the shorter time frames around the country.2 By adopting that provision, Arkansas made it relatively easy and fast to get a divorce.

But at the same time, Arkansas didn’t want to divorces to be too easy, and it definitely didn’t want to become a haven for people from other states who wanted out of their marriages. So, in order for a divorce to be granted, the law also required the person seeking a divorce to prove:

• “First. A residence in the state for one year next before the commencement of the action.”

• “Second. That the cause of divorce occurred or existed in this state, or, if out of the state, either that it was a legal cause of divorce in the state where it occurred or existed or that the plaintiff’s residence was then in this state.”

• “Third. That the cause of divorce occurred or existed within five years next before the commencement of the suit.”3

So the first requirement was a regular legal residence in the state for at least a year before you could file suit for divorce at all. You couldn’t just move into Little Rock from, say, St. Louis in April and then file suit for divorce in May.

The second requirement was that the cause for the divorce — the desertion, the adultery, whatever ground you were using — had to have some relationship to Arkansas. It was enough if the bad conduct happened in Arkansas or if it happened while the plaintiff was living in Arkansas. But if it happened out of state to a plaintiff living out of state, then it had to be recognized as grounds for divorce in that other state. That kept people from running into Arkansas and staying for a year only to be able to sue for a divorce they couldn’t get in their home states.

The last requirement was that whatever it was that you were complaining about couldn’t be ancient history: it had to have happened (or continued) within the five years before you filed suit. You couldn’t catch the old man foolin’ around in 1880, forgive him, take him back, and then file suit based on the 1880 adultery in 1890.

So, in Arkansas matrimonial law, then — and in the laws of every state that allowed divorces then — it’s about time. These phrases may look like boilerplate — the kind of things our eyes glaze on past when we see it in a document — but in fact they’re critical elements of what a plaintiff had to prove, and what the court had to find, for a valid divorce.

SOURCES

- Chapter LII, Divorce, § 2556, in William W. Mansfield, compiler, A Digest Of The Statutes Of Arkansas: Embracing All Laws Of A General And Permanent Character In Force At The Close Of The Session Of The General Assembly Of One Thousand Eight Hundred And Eighty-Three (Little Rock : Mitchell & Bettis Printers, 1884), 580; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 10 Apr 2012). ↩

- The time frames ranged from one year to as much as five years and some states such as Michigan, New York and South Carolina did not grant absolute divorces for desertion at all. See U.S. Census Bureau, Marriage and Divorce 1867-1906, Part I: Summary, Laws, Foreign Statistics (Washington, D.C. : Govt. Printing Office, 1909), 281-327; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 10 Apr 2012). ↩

- Chapter LII, Divorce, § 2562, in Mansfield, A Digest Of The Statutes Of Arkansas, 581. ↩

Great post! My 2nd great grandparents divorced in 1859-60 in Florida and I have no way of knowing the cause. The courthouse burned in the 1870’s and there are no records. Can you tell me how to find the divorce statutes for that time period?

Tanya, the closest published statute book I can find for Florida for that time period is this one published in 1872. If you look at the chapter on divorce, you’ll see the marginal notes as to when various sections were enacted or amended. It looks pretty much as though the law in effect in your time period will be that reflected in this book. Good luck!

Judy, thanks so much for the link! Very helpful in understanding the laws about divorce in Florida during that time period although I may never know the reason behind the divorce.

Glad I could help, Tanya.

I had a Great Grandfather went missing in the time frame of 1897 and have heard that he was killed by a family member?

My Grandmother remarried in 1899 so either he was declared dead or she filled

papers for desertion.This was in Union County,Arkansas.How would I search those documents.

He also owned a grocery store there.

Any help would be appreciated.

Thanks Sandra

Sandra, your best bets are (a) the newspapers of the time and (b) the court records of the time. I’d start with the newspapers — check the Library of Congress digital newspaper index to see what might be available from that time and place.

My mother claims that in approximately 1964 she obtained an uncontested “quickie” divorce in Arkansas and that the “residency” requirement was filled by her spending ONE NIGHT in an Arkansas hotel before filing for the divorce. What i’ve read here makes me wonder about the truthfulness of her claim. She obtained the divorce after being legally separated from my father for six years. My mother and father were both residents of New York state at the time of this event, and my mother never remarried. She wanted the divorce just so she could close the books on her failed marriage. Is it possible that in the 1960s Arkansas law alloed for the kind of divorce she claims to have obtained?

No. Arkansas law at that time required residence for three months. Now if the absent party (your father) didn’t care and never challenged it, the fact that actual residence may not have been established would easily have been … um … overlooked.

Oops! A typo – I meant “allowed” not “alloed.” Sorry! Also, I forgot to mention that my dead-beat, absent father did not learn of the divorce until at least several months after the deed was done. I was in my mid-teens and had things that were more important to me than being the diarist of my families “sturm und drang.”