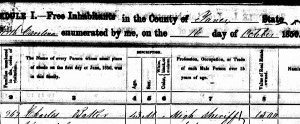

So what’s a high sheriff anyway?

After reading about Carson County, Nevada, High Sheriff John Blackburn earlier this week, reader Peggy Clemens Lauritzen wanted to know: “Why were some sheriffs called `high sheriffs’? Was there such a thing as a `low sheriff’?”

Great question! And, for the most part in most places in the United States, the answer is simple: the term usually was just the traditional way to speak of the sheriff of a county. The term in these cases sets the sheriff apart from any deputy sheriffs who may have been appointed from time to time.Most often, it’s not a matter of formal title created by statute or constitution, but rather a matter of long usage stemming from the original high sheriffs in England.1

The term “sheriff” itself is a blend of two words: shire — an English county,2 and reeve — in old English law, a ministerial officer who had functions of a constable.3 The resulting term was sheriff: “an officer of great antiquity, … also called the `shire-reeve.’”4

Historically, the high sheriff in England was responsible for maintaining law and order and executing the writs of the courts.5 The modern English High Sheriff, however, has largely ceremonial duties as an unpaid royal appointee.6

The term high sheriff came to the colonies with the English common law and was widely used in early America. Maryland used the term officially in the mid-1600s7 while in nearby Virginia numerous records referred to the high sheriff8 but the term itself didn’t appear in the statutes until 17879 and was rarely used in statutory references even after that.

That same pattern — using the term “high sheriff” to refer to the person elected to the office of sheriff even if the statutes didn’t designate the officer that way — persisted in many of the states well after colonial times. The term was last used in the 19th century in California (1864),10 Delaware (1811),11 Illinois (1875),12 Maine (1847),13 Maryland (1880),14 Michigan (1849),15 Missouri (1847),16 West Virginia (1899),17 and Wisconsin.18

And it persisted into the 20th century in Alabama (1988),19 Arkansas (1978),20 Georgia (1994),21 Kentucky (1951),22 Louisiana (1981),23 Massachusetts (2004),24 Mississippi (1970),25 New Jersey (1918),26 North Carolina (1987),27 Ohio (1911),28 Oklahoma (1915),29 Pennsylvania (1931),30, South Carolina (1912),31 Tennessee (1978),32 Texas (1994),33 Vermont (1979),34 and Virginia (1934).35

There were and are places, of course, where the term was official and not just a matter of tradition. In Connecticut, the elected sheriff was called a high sheriff in the state Constitution until it was amended in 2000.36 There is still one Executive High Sheriff in Rhode Island who heads a statewide sheriff’s department,37 a High Sheriff in Hawaii,38 and the county sheriffs in New Hampshire are called high sheriffs.39

And the Fulton County, Georgia, Sheriff is called the high sheriff, unofficially, because the state capital is located in that jurisdiction.40

With those exceptions, though, the term officially used today is simply “sheriff”:

The chief executive and administrative officer of a county, being chosen by popular election. His principal duties are in aid of the criminal courts and civil courts of record; such as serving process, summoning juries, executing judgments, holding judicial sales, and the like. He is also the chief conservator of the peace within his territorial jurisdiction.41

SOURCES

- See e.g. “The Origin of The Office of Sheriff,” Currituck County, NC (http://www.co.currituck.nc.us : accessed 6 Jun 2012). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 1093, “shire.” ↩

- Ibid., 1010, “reeve.” ↩

- Ibid., 1090-1091, “sheriff.” See also John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 6 Jun 2012), “sheriff” (the “name is said to be derived from the Saxon seyre, shire or county, and reve, keeper, bailiff, or guardian”). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “High Sheriff,” rev. 9 May 2012. ↩

- Ibid. See also “What is a High Sheriff,” High Sheriffs’ Association of England & Wales (http://www.highsheriffs.com : accessed 6 Jun 2012). ↩

- Proceedings of the Court of Chancery, 1669-1679; Archives of Maryland Online, Volume 51, Page 246 (http://www.aomol.net/html/index.html : accessed 6 Jun 2012). See also Kent Mountford, “Long arm of the law reaches back to Maryland’s colonial days,” Chesapeake Bay Journal, posted Nov 2010 (http://www.bayjournal.com : accessed 6 Jun 2012). ↩

- See e.g. the reference to an order issued to the high sheriff of James City County in the notes to William Waller Hening, compiler, Hening’s Statutes at Law, Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the first session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, 14 vols. (1819-1823; reprint ed., Charlottesville: Jamestown Foundation, 1969), 1: 430. ↩

- Ibid., “An act to encourage the speedy payment of arrearages of taxes into the public treasury,” chapter XI, Laws of Virginia, 1787, 12: 474-475. ↩

- Muller v. Boggs, 25 Cal. 175 (1864). ↩

- Nivin v. State, 2 Del. Cas. 281 (1811). ↩

- Grimshaw v. Paul, 76 Ill. 164 (1875). ↩

- Handley v. Call, 27 Me. 35 (1847). ↩

- State for the use of Vanderworker v. Brown, 54 Md. 318 (1880). ↩

- Calender v. Olcott, 1 Mich. 344 (1849). ↩

- Conway v. Nolte, 11 Mo. 74 (Mo. 1847) New York (1874),[17. Newman v. Beckwith, 61 N.Y. 205 (1874). ↩

- State v. Swann, 46 W. Va. 128 (1899). ↩

- Russell v. Lawton, 14 Wis. 202 (1861). ↩

- Oliver v. Townsend, 534 So. 2d 1038 (Ala. 1988) ↩

- Smith v. State, 264 Ark. 329, 338-339 (Ark. 1978). ↩

- Covin v. State, 215 Ga. App. 3 (1994) ↩

- Wells v. Board of Education, 244 S.W.2d 160, 161 (Ky. 1951). ↩

- Wattigny v. Lambert, 408 So. 2d 1126 (La. App. 1981). ↩

- Cape Cod Times v. Sheriff of Barnstable County, 443 Mass. 587 (2004). ↩

- Kent v. State, 241 So. 2d 657 (Miss. 1970). ↩

- Roth v. Roth, 90 N.J. Eq. 19 (Ch. 1918). ↩

- State v. Smith, 320 N.C. 404 (1987). ↩

- State ex rel. Heintz v. Hamann, 20 Ohio Dec. 615 (Hamilton Common Pleas 1911). ↩

- May v. State, 12 Okla. Crim. 108 (1915). ↩

- Commonwealth v. Morris, 302 Pa. 139 (1931). ↩

- Kirkland v. Allendale County, 128 S.C. 541 (1912). ↩

- Ramsey v. State, 571 S.W.2d 822 (Tenn. 1978). ↩

- McGowen v. State, 885 S.W.2d 285 (Tex. App. 1994). ↩

- Dowlings, Inc. v. Mayo, 137 Vt. 548 (1979). ↩

- Compton v. Commonwealth, 163 Va. 999 (1934). ↩

- Miller v. Egan, 265 Conn. 301 (2003). ↩

- See McCain v. Town of N. Providence, 41 A.3d 239 (R.I. 2012). ↩

- See Conner v. Haw. Paroling Auth., 2008 Haw. App. LEXIS 639 (Haw. Ct. App. Oct. 13, 2008). ↩

- See Hull v. Grafton County, 160 N.H. 818 (2010). ↩

- See “About FCSO,” Fulton County Sheriff Reserves (http://www.fultonsheriffreserve.com/ : accessed 6 Jun 2012). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 1090-1091, “sheriff.” ↩

I was on Ancestry and it said my relative 1586- 1661 had the occupation of “Sheriff’s Keeper”. Wad this an assistant to the Sheriff who was elected?

Probably not elected, and probably the jailer.

Thanks for the clarification.