The constable and the J.P.

You never can tell where you’re going to get your next hint about your family’s history. Sometimes it’s in something you read. And sometimes, if you’re lucky, since — as the t-shirt says, there are “so many books, so little time” — it’s in something someone else reads and tells you about.

A little more than two weeks ago, I got an email from one of my dearest friends, Betty Clay of Texas, who was reading what she described as a fascinating murder mystery novel based on a true story. And, she said, when she read about one of the real people featured in the novel, “For some reason, the name of David Baker, along with Burke County, NC, came to my ears in your voice.”

Oh yeah. David Baker, the elder, was my fourth great grandfather. A Revolutionary War soldier from Virginia, he and most of his mother’s family settled in Burke County around 1778.1 He became a Justice of the Peace there in 1797,2 and at least two of his sons — Thomas Baker, his oldest son by his first wife, Mary Webb, and David Davenport Baker, his second son by his second wife, Dorothy Wiseman — became Justices of the Peace in Burke County in their turn.3

And it was David the younger who showed up in the book Betty was reading… and oh, boy. Just plain oh boy.

The fact is, you just can’t have kin from western North Carolina, and particularly not from Old Burke County, and not know about Frankie Silver. She was born Frances Stewart (sometimes spelled Stuard) between 1810 and 1813, and lived in the area called Kona, in what’s now Mitchell County, North Carolina, about 7.5 miles as the crow flies from what’s now Bakersville, the county seat of Mitchell County, where the Baker family lived.

The fact is, you just can’t have kin from western North Carolina, and particularly not from Old Burke County, and not know about Frankie Silver. She was born Frances Stewart (sometimes spelled Stuard) between 1810 and 1813, and lived in the area called Kona, in what’s now Mitchell County, North Carolina, about 7.5 miles as the crow flies from what’s now Bakersville, the county seat of Mitchell County, where the Baker family lived.

I’d heard the story, of course. It’s one of the enduring, folk-loric tales of western North Carolina. How she and the boy next door Charlie Silver were married as teenagers. How they’d had one baby daughter. How just before Christmas in 1831, Frankie took an axe and killed Charlie in their cabin. How she hacked the body into pieces and, eventually, with the help of her family, burned as much of the body as she could. How a conjurer called in from Tennessee found what pieces remained of Charlie. How what was left was buried under three stones. How Frankie was arrested, tried, convicted, briefly escaped, recaptured, and eventually hung in Morganton, the Burke County seat, on the 12th of July 1833.4

The question of just what happened in December 1831 is clouded by time and, in part, by the quirk of the law that kept a defendant from testifying in his or her own behalf at the time. Was she, as some claim, the victim of spousal abuse who took up the axe only to defend herself and her baby daughter? Or was she a calculated killer? That question is explored in an able and very entertaining manner in the fiction book that my friend Betty was reading — Sharyn McCrumb’s The Ballad of Frankie Silver.5 Betty sent it on to me, and it’s good reading.

The question of just what happened in December 1831 is clouded by time and, in part, by the quirk of the law that kept a defendant from testifying in his or her own behalf at the time. Was she, as some claim, the victim of spousal abuse who took up the axe only to defend herself and her baby daughter? Or was she a calculated killer? That question is explored in an able and very entertaining manner in the fiction book that my friend Betty was reading — Sharyn McCrumb’s The Ballad of Frankie Silver.5 Betty sent it on to me, and it’s good reading.

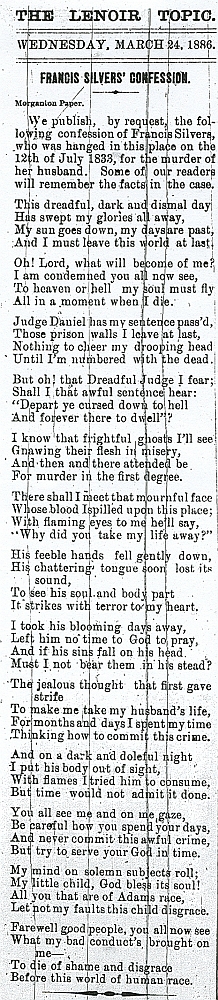

I knew much of the story, just as I knew that Frankie wasn’t the only woman hanged in Burke County, despite what her 20th century tombstone says, and just as I knew that Frankie actually didn’t say anything from the scaffold, despite the lengthy “Ballad of Frankie Silver” that she was supposed to have sung from the gallows (and that was printed as you see here in the Lenoir Topic in 1886).

And I knew there had been non-fiction books written about the case, as well — Perry Deane Young’s The Untold Story of Frankie Silver : Was She Unjustly Hanged?6 and Daniel W. Patterson’s A Tree Accurst: Bobby McMillon and Stories of Frankie Silver7 among them. There was even a documentary, The Ballad of Frankie Silver, by Tom Davenport, part of the American Traditional Culture Series of the University of North Carolina Curriculum in Folklore.

What I didn’t know, until spurred by Betty’s e-mail, was that my family played a not-insignificant role in the Frankie Silver case.

My third great grand-uncle David Davenport Baker was born 9 January 1801 in Burke County.8 He took the oath of office as a Justice of the Peace in Burke County in July of 1830.

And when Elijah Green swore out a complaint against Frankie Silver and her mother Barbara Stewart and her brother Blackstone Stewart on the 9th of January 1832, the Justice of the Peace who took the complaint was none other than David Davenport Baker. The complaint read:

This day came Elighe green before me D D Baker an acting Justice of said county and made oath in due form of law that Franky Silver and Barbara Stuard and Blackston Stuard is believed that they did murder Charles Silvers Contrary to law and against the dignity of the state worn to and subscribed to me this 9 day of January 1832.9

David then issued an order “to command some lawful officer to take the Bodies of the above named … to ansur the above charge and to be further delt with … as the law directs…”10 And the lawful officer who took custody of Frankie? Charles Baker, then a constable in Burke County.11

Yup. David’s youngest brother Charles, born in Burke County on 2 December 1806,12 another of my third great grand-uncles.

David then certified that the defendants were to be “committed to jail on the oath of Thomas Howeland, William Hutchins, Nancy Wilson, Elander Silver, Margaret Silver and Apon the word of the Jury.”13 Charles ended up serving the summonses to the various witnesses14 and, most likely, ended up taking the defendants to the County Jail in Morganton. David ended up testifying before the Grand Jury which indicted Frankie.15

There, the record of their involvement ends. None of the Bakers testified at trial, and none of them appear to have signed any of the many petitions sent in vain to the North Carolina Governors of the day for clemency. There’s no indication of any Baker involvement at all in the hanging — the moment when time ran out for Frankie Silver.

But life went on for my third great grand-uncles. In 1850, David was shown as a 49-year-old farmer, with his wife Lena (McGimsey) Baker, and their eight children — six daughters and two sons ranging in age from 3 to 16 — living in Yancey County, North Carolina, a child county to Burke and parent to Mitchell.16 Charles was shown as the 43-year-old High Sheriff of Yancey County, with his wife Mary (Keener) Baker and their six children — three sons and three daughters ranging in age from 4 to 19.17

By 1857, Charles was in Parker County, Texas, living near his older brother, my third great grandfather Martin Baker. He filed a land claim for 160 acres on Long Creek in Parker County on 21 October 1857, and Martin was one of the chain carriers for Charles’ survey.18 By 1860, David had joined them in Parker County,19 though he moved on to Collin County by 1870.20

The story of their involvement in the Silver case wasn’t passed down to their Texas-born-and-bred descendants and kin.

But we know about it now…

Thanks, Betty. Keep reading, will ya?

SOURCES

Tombstone image courtesy of Laurie Wasson.

- Affidavit of Soldier, 26 September 1832; Dorothy Baker, widow’s pension application no. W.1802, for service of David Baker (Corp., Capt. Thornton’s Co., 3rd Va. Reg.); Revolutionary War Pensions and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, microfilm publication M804, 2670 rolls (Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Service, 1974); digital images, Fold3 (http://www.Fold3.com : accessed 7 Sep 2012), David Baker file, pp. 3-6. ↩

- Minute Book, Burke County Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions, October 1795 – October 1798, Part II, minutes of 24 January 1797; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- For Thomas, see Minute Book, Burke County Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions, 1818-1829, Part I, minutes of January 1818. And for David D. Baker, see Minute Book, Burke County Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions, 1830-1834, minutes of 26 July 1830. ↩

- See generally Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Frankie Stewart Silver,” rev. 26 Jul 2012. ↩

- Sharyn McCrumb, The Ballad of Frankie Silver (New York : Penguin Group, 1998). ↩

- Perry Deane Young, The Untold Story of Frankie Silver : Was She Unjustly Hanged? (Asheboro, NC : Down Home Press, 1998). ↩

- Daniel W. Patterson, A Tree Accurst: Bobby McMillon and Stories of Frankie Silver (Chapel Hill, NC : University of North Carolina Press, 2000). ↩

- Josiah and Julia (McGimsey) Baker Family Bible Records 1749-1912, The New Testament of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ (New York : American Bible Society, 1867), “Births”; privately held by Louise (Baker) Ferguson, Bakersville, NC; photographed for JG Russell, Feb 2003. Mrs. Ferguson, a great granddaughter of Josiah and Julia, inherited the Bible; the earliest entries are believed to be in the handwriting of Josiah or Julia Baker. ↩

- Young, The Untold Story of Frankie Silver : Was She Unjustly Hanged?, Kindle edition, location 2750. ↩

- Ibid., 2754. ↩

- Ibid., 2764. ↩

- Baker Family Bible Records 1749-1912, “Births.” ↩

- Young, The Untold Story of Frankie Silver : Was She Unjustly Hanged?, Kindle edition, location 2792. ↩

- Ibid., 2778. ↩

- Ibid., 2831 ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Yancey County, North Carolina, population schedule, p. 412(B) (stamped), dwelling 421, family 441, David D. Baker; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 Sep 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 649. ↩

- Ibid., p. 450(A), dwell. 925, fam. 947, Charles Baker. ↩

- See Texas General Land Office, file 4492, patent vol. 33: 272, Charles Baker, 160 acres, issued 8 Dec 1863. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Parker County, Texas, population schedule, p. 12 (penned), dwelling/family 80, D. Baker; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 Sep 2012 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 1302; imaged from FHL microfilm 805302. ↩

- 1870 U.S. census, Collin County, Texas, Plano, population schedule, p. 462(B) (stamped), dwelling/family 46, David Baker; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 Sep 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M593, roll 1579; imaged from FHL microfilm 553078. ↩

That is a fascinating story! What a wonderful find. I enjoy your blog very much.

Thanks for the kind words, Liz! The Frankie Silver story is really riveting — and I had no idea any of my kin had been involved!

I have loved Sharyn McCrumb’s mysteries — particularly the ones with a historical background like Frankie Silver’s. Partly I gravitate to them because they are well-written and researched and compelling, but partly because, like you, I have family in the area. When you wrote about Yancey County, all the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. Yes! Mine left before 1850 to Lee Co, VA and thence west not long after. Did yours ever slide over the line to Johnson Co, TN. If so, you might want to look at the Perkins-White trial. A whole lot of people turned up there.

I don’t see any Johnson County folks in my Tennessee list… but White is a family name (intermarrying with Bakers) and I’m definitely going to look! Thanks, Barbara!

What a delightful story. I have to wonder if she was wrongly convicted, too. I also find quite a coincidence. I’ve been looking for the parents of Ephraim L. Rich who was born in Collin Texas around 1882. Is there a town Collin, too? In the 1900 census he is in Mendocino county, CA with my gggrandfather. Census says he is a nephew. Could be nephew, grand nephew, or… as gramps was 90 years old at the time.

Have to agree with the other writers, I thouroughly enjoy your blog.

Thanks for the kind words, Cyndy! The consensus of opinion is that she did in fact kill Charlie, but it was probably manslaughter or, at most, second degree murder and not first degree (premeditated, death penalty-type) murder. It may even have been self-defense. Part of the problem was that the legal strategy was to simply plead not guilty (putting the State to its proofs) on the theory that (a) she wouldn’t be convicted and (b) if convicted, the jury wouldn’t sentence a young mother to death. Her explanation of what happened came so late in the game that it wasn’t credited the way it might have been up front. Had the original plea been self-defense, things might have been very different.

I don’t know of a town named Collin in Texas, only the county. David ended up in Plano.

You are so careful with your terminology, I have to assume that great-grand uncle is correct, despite it seeming redundant. A great uncle is the brother of my grandparent. A great great uncle is the brother of a great-grandparent. But does one really say great-grand uncle? Wouldn’t one say just my 3rd great uncle? What is the correct usage? Perhaps it is a southern phrase?

Great uncle and granduncle have the same dictionary definition. When you’re adding in generations, however, it can get confusing. So I tend to use the same terminology as my genealogy program, while I think is easier to understand.

Judy,

Is the Constable, Charles Baker, in this story the same as the Baker Sheriff that supposedly left NC with some public money and left some of his Baker family having to make good on the money taken? I have read a few articles about this story but don’t know if it is true. Do you know the facts about the stolen money story?

It’s the same person, Jerry, but I haven’t been able to find any documentation about the story (which I’ve also heard) about the circumstances of his leaving NC for TX. I’m going to be out in SLC next month and hope to have time to review the court minutes for the years around when Charles left to see if they shed any light on this.

Hope you learn something that sheds light on the “absconded with public money story.” I have seen it mentioned in some books on the Western NC area. Some of Charles’ descendants do not believe it is true. I hope it is not true, but would like to know the truth either way and learn the truth about it. Please let us know if you learn anything.

I sure will let you know, Jerry. So far, all I’ve had time for is seeing that Charles wasn’t re-elected sheriff in 1851; a man named Gardner was elected instead. I haven’t had time to go carefully through the court minutes but so far I haven’t seen so much as a single reference to Charles Baker after Gardner became sheriff. Not to say it isn’t there, but I haven’t found anything yet.

I just left a comment on another post before I saw this and realized that we are distant cousins. David Baker is my 5th great-grandfather, through his son Thomas.

We are indeed distant cousins — I descend through the second wife and oldest son Martin.

I am a relative of Charlie Silver. Charlie’s father Jacob was my 4th gr grandfather Thomas’ s brother. I have discovered within the last few years a possible motive for the murder. The book “A Life for Nancy “ tells about what happened to Charlie and Frankie’ s daughter Nancy. They lived on George Silver’s land near his father Jacob. They were only teenagers at the time of the murders. Charlie’s grandfather George acquired his land through his distinguished service in the Rev War. Owning land back then was like gold. There was no money to give but there was plenty of land. The Stewart’s did not own much and wanted to go west. ( Franklin NC) Charlie did not want to leave his home and family. He had everything he needed right there. Here is the interesting part no one knows about but was revealed in the book. When Charlie was a young boy he inherited 100 acres along with another cousin who inherited another 100 acres from his great Uncle William Griffith. William was the brother of Charlie’s grandmother Nancy Griffith Silver. He was well to do but had no children. When Nancy became of age to marry. Nancy’s ( Stewart ) grandmother gave her the DEED to this 100 acres. She had held on to it since she was a baby. Why it was in her possession is strange. Now this was Silver property and Nancy being the only heir should have inherited it but it should have come from Charlie’s family not the Stewart. The cabin was burned down by the Silver family after the murder. The constant reminder of what happened there was unbearable. Nancy was being raised by Charlie’s parents on the Silver homestead. The Stewart’s came into the house and took baby Nancy. They did not know where they took her. The book was a real eye opener for me. I really get upset when people speculate what happened and paint a picture of him being a womanizer and not taking care of his family. Frankie was going to speak her last words on the gallows and her father told her to “ die with it in ye Frankie. “ I am convinced he had something to do with the murder. The puzzle pieces are finally coming together due to this Stewart book. I really enjoyed reading it. Little Nancy had a tragic and hard life.