The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

Reader Charlie Purvis carefully and painstakingly transcribed a four-page deed from 1880 involving three town lots and other land interests in Cheraw, Chesterfield County, South Carolina, and even after he finished the transcription, wasn’t quite entirely sure just what the land deal was all about. The problem was that the deed used a term he hadn’t come across before — it referenced the creation of Cestui Que Trusts.

So, Charlie asks, “In bunny rabbit English, what is a Cestui Que Trust?”

Let’s go over this land deal, because it’s the context here that helps understand the term.

Let’s go over this land deal, because it’s the context here that helps understand the term.

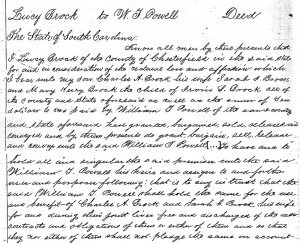

The deed, recorded 23 March 1880, began as follows:

Know all men by these presents that I Lucy Brock of the County of Chesterfield in the said state for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which I bear unto my son Charles A. Brock his wife Sarah J. Brock and Mary Kerry Brock the child of Irvin S. Brock all of the county and state aforesaid as well as the sum of Ten Dollars to me paid by William T. Powell of the same County and state aforesaid have granted, bargained, sold, released and conveyed and by these presents do grant, bargain, sell, release and convey unto the said William T. Powell those parts of three lots in the town of Cheraw … (and other interests in property)…1

So right here at the beginning, we have two things going on. First, in the usual legal language (“granted, bargained, sold, released and conveyed”), Lucy transferred legal title over the town lots and her interest in other properties to one William T. Powell of Chesterfield County. But the consideration — the price paid — was her “natural love and affection” for three people: her son Charles, his wife Sarah and a third Brock family member, Mary Brock. That’s an immediate signal that this isn’t a routine “I’m selling, you’re buying” type of land deal.

Lucy (Morris) Brock (1822-1887) was the widow of Alsey Brock of Chesterfield County, Charlie’s second great granduncle. Alsey died in 1848 and, as far as Charlie has determined, the Brocks had only two sons, Charles and Pleasant. By the time of this land deal in 1880, Pleasant had also died.2 Where exactly Mary fit into the family is yet to be determined.3

The deed then limits the transfer in very substantial ways:

that is to say in trust that the said William T. Powell shall hold the same for the use and benefit of Charles A. Brock and Sarah J. Brock his wife for and during their joint lives free and discharged of any debts, contracts and obligations of then or either of them and so that they nor either of them shall not pledge the same on account thereof and after the death of either of them then to hold the said in trust for the sole and separate use, behalf and benefit of the survivor of them for his or her natural life and free and discharged of the debts, contracts and liabilities of such survivor4

Okay, here we’ve got two very big restrictions. First off, while Powell got legal title to the land, he wasn’t the owner in fee simple. He couldn’t sell it, give it away, leave it in his will for use as a home for wayward cats. He was a trustee, holding title but only in trust for the use and benefit of Lucy’s son and daughter-in-law, for their joint lives and thereafter for the life of the survivor of the two. And note the restriction on the son and daughter-in-law: they couldn’t encumber the land in any way. They couldn’t mortgage it, or pledge the land as security for any kind of debt. Clearly, Mama was a little concerned about Sonny and his wife here.

And the restrictions continued:

in further trust after the death of both the said Charles A. Brock and Sarah J. Brock without leaving any child or children living at the time of their death or in case the said Charles A. Brock shall die without leaving any child or children by any wife he may hereafter marry then to hold the same in trust for Mary Kezzie Brock the child of Irvin S. Brock should she continue to live with the said Charles A. Brock and Sarah J. Brock during their joint lives or with the survivor of them during his or her natural life (but her marriage shall not be a breach of the condition and in that event she shall be at liberty to leave this without forfeiting her interest herein) and for such child or children of the said Charles A. Brock by any wife he may have share and share alike.5

We know from this language that Mary Kezzie Brock (called Mary Kerry Brock in an earlier paragraph) was living with Charles and Sarah as a child in their household and was to share equally with any children Charles might have — by Sarah or any other wife — if she continued to live with them (unless she married). Notice that the land is still supposed to be in trust, however. Nobody in the Brock family was yet to have legal title to this property even after Charles and Sarah died.

And Mama wanted to make sure that she could live on the property for her lifetime, so she reserved for herself a life estate, requiring the trustee to “allow (her) to have, use, occupy and enjoy any of the premises aforesaid during (her) natural life.”6

The deed did provide for the trust to end in any of three ways: (1) if Charles had one or more children living at the time of his and Sarah’s deaths and Mary Kezzie lived with Charles until her marriage and had a child, then to Charles’ child or children and Mary Kezzie jointly, share and share alike; (2) if Charles had no children but Mary Kezzie lived with Charles until her marriage and had a child, then to her and her heirs; or (3) if Charles had no children and Mary Kezzie either didn’t continue to live with Charles or didn’t marry and have a child, then “to Sarah Brock the widow of Hezekiah Brock and her heirs absolutely free from all trust.”7

And that’s where the weird legal language was used: “that is to say after all the aforesaid Cestui Que Trusts have ceased to exist or cannot by the terms thereof claim any interest in the same.”8

So… what’s a Cestui Que Trust? Purely and simply, the beneficiary of an estate held in trust. Here, Charles and his wife Sarah and Mary Kezzie Brock were the Cestui Que Trusts of this deed.

The term is legal French this time, as opposed to legal Latin. Imported to England and the common law by the Normans, to the total infuriation of American legal lexicographers.

Henry Campbell Black politely defined the term — “He who has a right to a beneficial interest in and out of an estate the legal title to which is vested in another. … The person who possesses the equitable right to property and receives the rents, issues, and profits thereof, the legal estate of which is vested in a trustee” — and then snarled:

It has been proposed to substitute for this uncouth term the English word “beneficiary,” and the latter, though still far from universally adopted, has come to be quite frequently used. It is equal in precision to the antiquated and unwieldy Norman phrase, and far better adapted to the genius of our language.9

John Bouvier in his Law Dictionary was no happier. He called it “a barbarous phrase, to signify the beneficiary of an estate held in trust.”10

So, in “bunny rabbit English,” it’s not English at all — it’s a “barbarous” “uncouth” holdover from the Norman French. Think “beneficiary of an estate in trust” instead.

After all, you wouldn’t want those American law dictionary authors to be spinning in their graves.

SOURCES

- Chesterfield County, South Carolina, Deed Book 5: 782-786, Brock to Powell, 23 Mar 1880; Register of Deeds, Chesterfield; digital copy provided by Charles Purvis. ↩

- Charles Purvis, “Tombstone Tuesday – Alsey Brock,” Carolina Family Roots, posted 24 Jul 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 25 Sep 2012). ↩

- If you have information about her, let me know and I’ll put you in touch with Charlie, who’d love to hear from you! ↩

- Chesterfield Co., S.C., Deed Book 5: 782-786, Brock to Powell. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 189, “Cestui Que Trust.” ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 25 Sep 2012), “Cestui Que Trust.” ↩

Thank you so much for explaining this deed in simple terms.

Charlie

Thank you so much for sharing such an interesting question, Charlie!