Online deeds record lives

They were old. They were young. They were middle-aged. They were men and women. They were boys and girls. They had first names only in most cases. Sometimes they had descriptions.

And they were bought, sold, seized for debt, distributed as parts of an estate, given away.

They were slaves in Buncombe County, North Carolina, and their transfers of ownership are recorded in an extraordinary set of records made available online by the Buncombe County Register of Deeds.Buncombe County, with its county seat of Asheville, was created from parts of Burke and Rutherford Counties in 1791 (effective 1792), and named after Col. Edmund Buncombe, a Revolutionary War soldier.1

Slavery was not as prevalent in mountainous western North Carolina as it was in the flatter central and coastal areas of the state. As of 1800, there were 5465 free residents of Buncombe County recorded in the U.S. census, and only 347 slaves. Only three slaveholders owned as many as 10 slaves — David Vance, with 10; John Patton with 15; and William Mills with 20.2 Even as late as 1850, when many more slaveholders in Buncombe County owned multiple slaves, no-one from the county was among the 91 slaveholders around North Carolina who owned 100 slaves or more.3

And the very fact that slavery was less prevalent in that far western county may make it even more chilling that some 309 transactions in all covering the years between the county’s formation and the Emancipation Proclamation were recorded in the deed books of Buncombe County.

The Register of Deeds website for these records explains:

The Buncombe County Register of Deeds office has kept property records since the late 1700’s. In our records one can find a wealth of information about the history of our community. …(W)e have compiled a list of the documents that record the trade of people as slaves in Buncombe County. These people were considered “property” prior to end of the Civil War; therefore these transfers were recorded in the Register of Deeds office. …

The Register of Deeds Office presents these records in an effort to help remember our past so we will never again repeat it.4

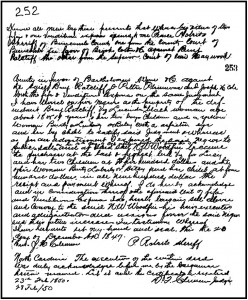

The quality of the images varies — many are easy to read; some are barely legible. The interface is a bit cumbersome. On the opening page, a scrollable list presents the transactions in the order in which they were recorded, from Deed Book A, page 91 (recording the 14 November 1805 sale of “one Negro man by the Name of Ned of the age of Twenty Seven” for $350 by Adam Cooper to James Reed and James Rutherford) to Deed Book 27, page 338 (recording the 3 April 1863 sale by Henry Ray to James Weaver of “a Negro Girl named Sarah aged ten years” warranted to be “sound in body & mind and a Slave for life” for $1400).

Each list entry has a hot link to the book and page on which the record appears. Clicking the hotlink slowly loads a second page, listing the documents available to view. Clicking on the image icon for the document causes a warning to display for the application View One, required to see the images. It says the application’s digital signature has an error (because it has expired), but clicking Run allows the image to display. Each image can be downloaded, printed, zoomed, etc., using the control icons above and to the left of the image.

Reviewing the images is stunning — you can’t look at these documents without realizing how lives were being affected. There was the simple gift on 21 October 1806 from a mother to daughter — Mary Flack the mother to Mary Flack the daughter — of “one Negro Girl Named Seel now of the age of Six years old and also one Negro Woman Named Luse.”5In counterpoint to that, there was the seizure by the sheriff of five slaves owned by Benjamin Ratcliff and sold to N.W. Woodfin on 20 December 1847 to satisfy a judgment: “Lucinda a black woman about 18 or 19 years & her two boy children and a yellow woman Busty or Lubusty or Betsy … and her boy child” for a total of $900.6

And that very last deed in the record set: 10-year-old Sarah, sold on 3 April 1863, for $1,400,7 just three months after the Emancipation Proclamation became effective — and, of course, ineffective in Confederate-controlled Buncombe County. You can’t help but wonder… did she make it through to freedom?

The Register of Deeds had the assistance of the Center for Diversity Education, an educational foundation located on the campus of the University of North Carolina-Asheville, in producing the record set.

Whether or not you have enslaved or slaveholding ancestors, from Buncombe County or elsewhere, the whole set is worth a careful look. And kudos to the Register of Deeds for making it readily accessible online.

SOURCES

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Buncombe County, North Carolina,” rev. 4 Sep 2012. ↩

- “Buncombe County, NC, 1800 Census,” Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society (http://www.obcgs.com : accessed 30 Sep 2012). ↩

- See 1850 U.S. census, Buncombe County, North Carolina, slave schedule, 21 pages; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 30 Sep 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 650. See also “October: African Americans & Free People of Color,” Family History: State Library of North Carolina (http://statelibrary.ncdcr.gov : accessed 30 Sep 2012) (“DID YOU KNOW? By 1850, 91 slave holders in North Carolina owned over 100 slaves”). ↩

- “Slave Deeds,” Register of Deeds, Buncombe County, North Carolina (http://buncombecounty.org/Governing/Depts/RegisterDeeds : accessed 30 Sep 2012). ↩

- Buncombe County, North Carolina, Deed Book A: 146, Flack to Flack, 21 Oct 1806; Register of Deeds, Asheville; digital images, Register of Deeds, Buncombe County, North Carolina (http://buncombecounty.org/Governing/Depts/RegisterDeeds : accessed 30 Sep 2012). ↩

- Buncombe Co., N.C., Deed Book 24: 252-253, Sheriff to Woodfin, 20 Dec 1847. ↩

- Buncombe Co., N.C., Deed Book 27: 338, Ray to Weaver, 3 Apr 1863. ↩