Looking good

Back in August, The Legal Genealogist was musing about the potential for secret relatives — secret only because you didn’t know about them yet, hadn’t met them yet, not because there was any deep dark family secret about their existence.1

And, you may recall, I was crossing my fingers, toes, arms, legs, eyes and anything else that might ever be crossed that one of my secret relatives might be about to come out and play in the sunshine, thanks to autosomal DNA.

And, you may recall, I was crossing my fingers, toes, arms, legs, eyes and anything else that might ever be crossed that one of my secret relatives might be about to come out and play in the sunshine, thanks to autosomal DNA.

Here’s what the problem was:

My great grandmother Eula was born in 1869 in Cherokee County, Alabama — a burned county so there aren’t any records of a marriage of her parents.2 The only census where she was enumerated in her father’s household — or what we hoped was her father’s household — was the 1870 census, and it was… um… “odd” is a good word. The line for head of household simply reads “Baird” without a first name. And the details simply say age 22, a farm hand, born in Alabama.3

There aren’t any other records that we’ve been able to find to help identify Eula’s father. Her Texas marriage record doesn’t name her parents.4 She never had a Social Security number, so no SS-5. Her death certificate names her stepfather, A.C. Livingston, instead of her father.5 There’s no family Bible, no baby book, no artifacts to help nail it down.

All we have, basically, is a family story, passed down from Eula to her daughter, my grandmother, that Eula’s father was Jasper Baird, son of “Billy” Baird,6 who took the wagon out one day into Indian country around 1870-1871 and was ambushed; the wagon was found, the story says, but Jasper’s body never was. One version of the story says this happened in Alabama (where there hadn’t been an Indian attack in decades); another says it happened in Oklahoma (where nobody from the family lived until after 1900).

Now it’s true that there was a William Baird family on the 1860 Cherokee County census with a son Jasper old enough to have been Eula’s father.7 William and Christian Baird had moved their family to Pope County, Arkansas, by 1870, but their son Jasper wasn’t enumerated with them there,8 so maybe, just maybe, he was Eula’s father.

Except for the minor little detail that that particular Jasper Baird didn’t die in any Indian attack anywhere and, in fact, didn’t die at all until 1909, in Pope County, Arkansas.9

We’d known for years that ordinary DNA testing couldn’t help us with this problem. Since we descend from a daughter, not a son, and daughters don’t have any of their father’s Y-DNA, we couldn’t test against a son of a son of William Baird for Y-DNA.10 And since Eula got her mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from her mother, not her father, we couldn’t test against a daughter of a daughter of Christian Baird for mtDNA.11

And then along came autosomal DNA testing, making it possible to test across gender lines. And, in August, along came a descendant of William and Christian Baird to test against Eula’s descendants.

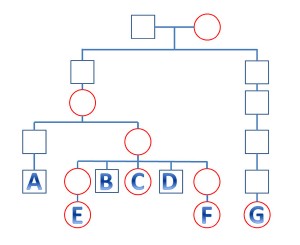

Connie Baird Bowen — G on this chart — is a third great grandchild of William and Christian (Campbell) Baird. That makes her a fourth cousin to me (I’m E on the chart) and to a first cousin of mine (F on the chart), and a third cousin once removed to the members of the earlier generation of my family who’ve been tested (A is my mother’s first cousin, B and D my mother’s brothers, and C my mother’s sister).

Connie Baird Bowen — G on this chart — is a third great grandchild of William and Christian (Campbell) Baird. That makes her a fourth cousin to me (I’m E on the chart) and to a first cousin of mine (F on the chart), and a third cousin once removed to the members of the earlier generation of my family who’ve been tested (A is my mother’s first cousin, B and D my mother’s brothers, and C my mother’s sister).

The fact that we’re dealing with third and fourth cousins made the odds of a match a real crapshoot.

That’s because, with each generation, the amount of DNA passed down from any particular ancestor gets smaller and smaller. On average, third cousins once removed share less than four-tenths of one percent of their DNA; fourth cousins only 0.195%.12

Put simply, that meant it was entirely possible that we could be related to Connie in the Baird line, and yet not show up as a match at all.

So it was with no small amount of trepidation that I discovered this past week that Connie’s autosomal DNA results had come in. The odds of a match to me or to the other cousin in my generation weren’t all that good. It’s a 50-50 shot, and for some reason my family has repeatedly demonstrated some very odd inheritance patterns that may make our particular chances a little worse than average.

And, sure enough, neither my first cousin nor I matched Connie. One of two reasons, of course. The best we could hope for was that we just didn’t have enough DNA in common to be detected as a match. The worst … that we really weren’t related at all.

It was going to turn on the slightly better chances that at least one of four members of our earlier generation were going to turn up as a match.

I looked at the results for my cousin Michael, a first cousin to my mother’s generation. No match.

The results for my uncle Michael. No match.

Paydirt.

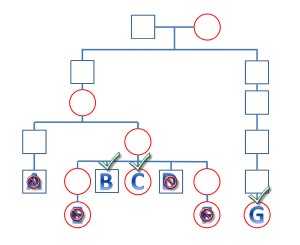

Both my uncle David and my aunt Carol matched Connie.

In fact, Carol is a solid match both in terms of overall DNA in common and the longest segment shared, and although David’s total overall amount of DNA in common with Connie is smaller he shares that same big segment with Connie that Carol shares.

So the chart to the right here shows how the random chance of autosomal genetic genealogy played out in this case: at Family Tree DNA — where all of these tests were performed — only two of the six people tested in my line show up as matches for Connie. Proving, once again, why it’s so important to test as many people as you can afford to test.

And comparing the results on Gedmatch, where it’s possible to look at smaller segments than are reported by the major testing companies, it turns out that all six of us in my line do have at least some DNA in common with Connie, and often a fair amount of DNA in common, just not with any one chunk big enough to warrant being reported as a match.

For example, Connie and I have as much overall DNA in common as many matches do, but the longest segment we have in common is only 3.8 centimorgans (cM) in length. The one uncle who didn’t show up as a match at Family Tree DNA has nearly as much overall DNA in common with Connie as his brother and sister, but his longest shared segment is only 4.0 cM in length.

And a careful look at our paper trail family tree information against Connie’s paper trail strongly suggests that the only possible line that we have in common is the Baird line.

This one test, without that paper trail analysis, wouldn’t prove a thing.

With it, however, all I can say is…

Thanks, matchmaker, for the match.

SOURCES

- Judy G. Russell, “Matchmaker, matchmaker, make me a match,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 26 Aug 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 6 Oct 2012). ↩

- The earliest available marriage records in Cherokee County begin in 1882. See “Local Government Records Microfilm Database,” Cherokee County, Alabama Department of Archives and History (http://www.archives.alabama.gov : accessed 25 Aug 2012). ↩

- 1870 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, population schedule, Leesburg Post Office, p. 268(A), dwelling/family 15, Baird household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 Aug 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M593, roll 7; imaged from FHL microfilm 545506. ↩

- Bexar County, Texas, Marriage Book N: 24, marriage license and return no. 14,298, Robertson-Beard, recorded 21 Feb 1896; County Court Clerk, San Antonio, Texas. ↩

- Virginia Department of Health, Certificate of Death, state file no. 6367, Eula Robertson (1954); Bureau of Vital Statistics, Richmond. ↩

- Interview with Opal Robertson Cottrell (Kents Store, VA), by granddaughter Bobette Richardson, 1980s; copy of notes privately held by Judy G. Russell. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Cherokee County, Alabama, population schedule, p. 136 (stamped), dwelling/family 332, Wm. G. Baird household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 Aug 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 5. ↩

- 1870 U.S. census, Pope County, Arkansas, population schedule, Dover Post Office, p. 383(B) (stamped), dwelling 614, family 630, William Baird household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 25 Aug 2012); citing National Archive microfilm publication M593, roll 61; imaged from FHL microfilm 545560. ↩

- “J.N. Baird Dies Suddenly,” The (Russellville, Ark.) Courier Democrat, p.2, col.3. ↩

- See “Genetic Genealogy Q&A for Beginners,” FAQ 28, International Society of Genetic Genealogy (http://www.isogg.org : accessed 25 Aug 2012). ↩

- “Understanding DNA,” Family Tree DNA (http://www.familytreedna.com : accessed 25 Aug 2012). ↩

- ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Autosomal DNA statistics,” rev. 26 Apr 2011. ↩

Goodness, Judy – so close… and so exciting! And with so many puzzles and mysteries still to poke at. I can see the value of doing as many tests across one’s extended family now, with these results. Thanks for the clear explanations!

I could use a few fewer puzzles and mysteries, Celia! But yeah, it really is fun.

Congratulations on your DNA Success Story. Thanks for writing about the role “small segment genealogy” played in your success. “Matchmaker, Matchmaker Make Me a Match” is the mantra of the genetic genealogist. The good matchmaker also wants to know the nature of the match she has made. That story is often told by those small segments that don’t make it into the wedding.

You footnote 12 has a link which deserves to come to the front of the stage. “Genetic genealogy and the single segment” by Steve Mount is the best explanation I have found of what segments are, and what they mean.

Thanks so much, David! I need to spend more time making sure I completely understand the small segment stuff, so I’m most appreciative that you highlighted that link.

Thanks to your posts, I am beginning to make some sense of my autosomal DNA results.

We’re all struggling with this, Diana. None of it is easy!!

What test would be most helpful in revealing the ethnicity of my wife’s father? He was adopted and we know his mother, but not his father. Depending on what family member I talk to, his father could have been a circus performer of half Filipino, half Puerto Rican parentage, or a Greek restaurant owner.

My wife’s father and his three brothers are all dead, so the only people alive now to test are the children of of these siblings. The closest to my wife are a half brother and a half sister. Then there are a few first cousins from her father’s brothers. Who should be tested to determine the ethnicity of my wife, her father and his father?

If what you really want is ethnicity — the admixture and not the identity of the people involved — then having your wife tested with the Geno 2.0 project from National Geographic Magazine is probably your best bet. It’s likely to be the best, most precise measure of that sort of ancestry that anyone has, beating out the commercial testing companies. If what you want is a genealogical shot at identifying your wife’s father, then I would test her using the Family Finder test at Family Tree DNA (largest group of people who test solely for genealogical purposes). And if you can afford both, do both. One other thing you can consider doing is testing one or both of her half-siblings (mother’s children, I assume) with Family Finder so you can differentiate between matches that are on her mother’s side and matches that must come from her father’s side. Testing the sister might be best for this since you’d get the benefit of the X chromosome testing, and both would have some totally in common (the X from their mother) and some totally different (the X from their father).

In all you had seven members tested for this experiment. At a conservative price of $250 per test, this cost $1750 in DNA tests alone. Since you needed a paper trail as well, and it seems you paid at least one visit to Alabama from New Jersey to do so, I’ll conservatively put the paper research price tag at $1000. So it cost about $2750 to prove this one great-great-grandparent (Jasper Baird) into his parents. (although technically it was the ancestry of your great grandmother). You have 16 great-great-grandparents, so a total cost on average with this autosomal DNA route would be about $44,000 to do all 16 great-greats. Some of the cost is transferrable. You only need to be tested once for it to help in all lines. However, some of the paper trail will be harder than others and require more travel. Don’t you think this puts genealogical research out of the reach of the average person? Especially anyone with a family? Genealogy has always been an expensive hobby (to do properly) like skiing or golf. However, the online world is trying to make it cheaper for the average person. Aren’t these two worlds going to collide a bit? Lastly, are you going to write this up and publish it? How are you going to feel when you see an online family tree with Jasper and William Baird that doesn’t credit you with this discovery?

Martin, only a person with (a) a brick wall and (b) a DNA route that might solve the brick wall can decide if doing DNA testing is worth it. If it is, then you look to see if you can find the resources to do it. If it’s not, or the resources can’t be found, you keep hammering away at the wall with the traditional paper-trail chisel. Making a new tool available doesn’t make the old tools any less available or any more or less affordable — it simply adds one more option for those who choose (and are willing to allocate resources) to use it.