Public aid for needy women and children

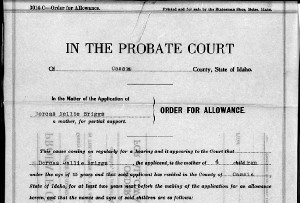

Her full name was Dorcas Nellie (Cummins) Briggs and she was 39 years old when she went before the Probate Court in Cassia County, Idaho, on 9 May 1923, and said she needed help to feed her children.

She was born, she said, in Oakley, Idaho, and married Oscar L. Briggs, a Tennessee native, in Salt Lake City on 2 October 1903. He died in Baker City, Oregon, of heart trouble on 30 April 1923, leaving no insurance and no property. She had six children ranging from two to 19 years of age and she named them and gave their dates and places of birth. She’d lived in Cassia County since she was born on 26 November 1883 to F.M. Cummins and Desert Cummins, both deceased. She named her five brothers and five sisters and listed where they lived, and named both her husband’s parents and his five living sisters.1Ten years later, in April 1933, Florence Jones was 42 years old when she made her application to the same court in Cassia County. She named all eight of them, ranging in age from 20 down to five, and listed their birthdates and birthplaces. She had lived in Cassia County all of her life, married there on 20 February 1912, and had lost her husband Jessie David Jones to appendicitis; he had died at the L.D.S. Hospital in Salt Lake City on 16 December 1931. She had no life insurance, and her only asset was a 240-acre ranch “but it is all pasture land and mortgaged.”2

As genealogical records go, it doesn’t get much better than this… and there are thousands and thousands of these records all over the United States, created in the early years of the 20th century. They are variously named but most of them — like these Idaho records — are applications for an allowance under a pension act of one of the states benefiting mothers and orphans.

These laws which, for the very first time, allowed for financial assistance to needy parents to keep their children in their own homes with them, marked a sharp break with the past, when children whose fathers had died were routinely bound out to others if their mothers didn’t have the assets to care for them. In Virginia, for example, has far back as the 1660s, the law had provided that if an orphan’s estate wasn’t enough for the child’s support, the child was to be “bound apprentices to some handycraft trade untill one & twenty years of age, except some kinsman or relation will maintain them for the interest of the small estate they have.”3

Private charities had stepped in to the gap, particularly in some large cities, as the population grew, but many of those charities required mothers to put their children into orphanages or foster care, even though that was generally far more expensive than keeping the children in their own homes. The notion of public aid for mothers and children wasn’t even seriously considered until 1898, when the New York legislature passed a bill to provide relief to New York City widows. It didn’t become law because the governor refused to sign it.4

What changed was the attention of the government to those higher costs of out-of home care, starting with the 1909 White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children. That conference concluded:

Home life is the highest and finest product of civilization. It is the great molding force of mind and of character. Children should not be deprived of it except for compelling and urgent reasons. Children of parents of worthy character, suffering from temporary misfortune and children of reasonably efficient and deserving mothers who are without the support of the normal breadwinner, should as a rule, be kept with their parents, such aid being given as may be necessary to maintain suitable homes for the rearing of children…5

Even that conference didn’t outright call for public assistance; the emphasis continued to be on private charities. But the states had heard the call, and they began to respond.

On 7 April 1911, Missouri became the first state to provide any funding to care for children in their own homes. The act, which went into effect in June 1911, only affected Jackson County (Kansas City), followed by a law allowing St. Louis to bind children out to their own mothers. Illinois was next, passing a “funds to parents” act on 5 June 1911, effective 1 July, and Colorado followed with a referendum to adopt its “mother’s compensation act” at the November 1912 election, effective 22 January 1913.6

By 1920, some 39 states had statewide public cash assistance programs for mothers, and five more states adopted them in the 1920s. By 1937, all of the states had them:

• 1911: Illinois.

• 1913: California, Colorado, Idaho, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin.

• 1914: Arizona (declared unconstitutional in 1916).

• 1915: Kansas, Montana, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wyoming.

• 1916: Maryland.

• 1917: Arizona (to replace 1914 statute), Arkansas, Delaware, Maine, Missouri (statewide), Texas, Vermont.

• 1918: Virginia.

• 1919: Connecticut, Florida, Indiana.

• 1920: Louisiana.

• 1923: North Carolina, Rhode Island.

• 1926: Washington, D.C.

• 1928: Kentucky, Mississippi.

• 1931: Alabama, New Mexico.

• 1937: Georgia, South Carolina.7

The amounts awarded under the programs tended to be small — a typical award was $10 a month for the first child, $5 for each additional child, and often with a maximum award of $25 no matter how many children a woman had. Some programs were restricted to widows; some allowed grants if a husband was in prison or a hospital; and only two — Michigan and Nebraska — specifically allowed unmarried mothers to receive assistance.8

All of these early programs were set up to be run by local governments — usually the counties — and not all counties followed through. As late as 1931, only three counties of 82 authorized to run such programs in Mississippi and only 23 of 254 authorized counties in Texas paid out any money under these laws.9 Records, then, will be at the county level; few are likely to be online.

But where the programs existed, the records are simply amazing in the detail required in the applications: names, dates, places, circumstances and so much more. Because of that level of detail and because of the nature of the programs themselves, today’s genealogists need to keep in mind that some sensitivity is required in dealing with these records: what they evidence is that your parents or grandparents were on what today is termed welfare. But clearly these records are genealogical gems and it’s well worth making the effort to see if anyone on your branch of the family tree may have needed that kind of a helping hand from a county government under the statute in effect in your state.

SOURCES

- Cassia County, Idaho, Probate Court, application of Dorcas Nellie Briggs, 9 May 1923, Cassia County Courthouse, Burley; “Idaho, Cassia County Records, 1879-1989, Pensions, Mother’s pension records (applications and orders for allowance), 1919-1935” database and digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed 24 Oct 2012). ↩

- Ibid., application of Florence Jones, 11 Apr 1933. ↩

- ACT LXVI of March 1661, “Concerning Orphants,” in William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the first session of the Legislature in the year 1619, vol 2. (New York: p.p., 1823), 2:93. ↩

- Carolyn M. Moehling, “Mothers’ Pensions and Female Headship,” draft paper at 5-8, (http://www.econ.yale.edu/seminars/labor/lap02/Moehling-021004.pdf : accessed 24 Oct 2012). ↩

- Ibid., citing Mark H. Leff, “Consensus for Reform: The Mothers’-Pension Movement in the Progressive Era,” Social Service Review 37 (1973): 397-429. ↩

- U.S. Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau, Laws Relating to “Mothers’ Pensions” in the United States, Denmark and New Zealand (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1914), 7. ↩

- Moehling, “Mothers’ Pensions and Female Headship,” draft paper at 6, 22. ↩

- Ibid. at 6. ↩

- Ibid. at 6-7. ↩

This is great information Judy! While Kentucky adopted the assistance program too late to help my great grandmother with her 5 children after her husband died, she was very fortunate that he had been a Master Mason and therefore she had the wonderful charitable help of the Louisville Masonic Home (orphanage) for several years while she took in mending and worked full time as a teacher to make enough money to bring her children home again. The Louisville Masonic Home was more than happy to send me their records just for the asking. The Masons are another great source of information on family assistance services.

Oh, that’s really terrific information, Lisa. All of those organizations — Masons and more — are great sources if we just think to look!

That’s a great idea! Not one that some or most of us would have thought about. I have several ancestors that were Masons of one sort or another.

And if you have ancestors who were union members, or members of Woodmen of the World, or any of a host of other organizations, look there too, Jeff!

How interesting! I didn’t even know these records existed. I wonder if anyone has abstracted any of them. I think that would be a fun project.

The records can be fascinating, Michele. They’re certainly heart-wrenching in some cases.

I viewed the book on the Mother’s Pension, for Lyon County MN, at the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul. This case: the father died young, had 3 girls, a grand aunt took in one girl and was getting the Mother’s Pension for the girl, while they lived in Hennepin County MN. It was reported the girl married when she became 16 and the pension stopped. I was looking at a ledger book from Lyon County MN. The other two girls went to another state to live with a relative. I did not follow up if that relative was getting the Mother’s Pension.

It’s very interesting to know that the grand aunt qualified for the pension, Suzanne! Thanks for sharing that info.

I believe my grandmother applied for Mothers Pensions in New York City (Staten Island) in 1920 and I have been searching for the records for the past 5 years. I contacted the National Archives who then referred me to the NY State Archives. The NY State Archives referred me back to the National Archives. I tried NY State Archives again and they referred me to the NYC Municipal Archives. They told me to try the NY Historical Society who then referred me back to the NYS Archives. I tried the NY Genealogical & Biographical Society (NYG&B), the records room of the NY State coursts (courts.state.ny.us), the Columbia University library, familysearch.org, and the Staten Island Probate Court. I know the records must be collecting dust somewhere but I have run out of ideas. Would you have any suggestions? Thanks so much.

These would definitely NOT be federal records, Janet, so forget the National Archives. In New York State, the pensions were called “widow’s pensions” under the Hill-McCue legislation of 1915. Records were originally kept by the child welfare boards of the counties. I’m really not familiar with NY records generally but that background info may help you track them down. You might also want to read a report available on Google Books on New York widows’ pensions from around 1917 as background. Good luck!!

Thank you for your fast response. I stumbled on your blog by accident and immediately subscribed. I was glad to see someone else address these valuable records. I have to keep telling people that I am not looking for records on Civil War pensions. I have also posted on various message boards and checked with the NY City Hall library. Thank you again.

Hi Janet,

I’ve been looking for these records as well. They were most likely part of social services records because the Mothers’ Pension program later became the ADC program in the 1930s. I contacted social services in NYC, and they said that the records they have from that period have been destroyed, but they couldn’t confirm if they were ever in possession of the records.

I am wondering if you were successful… I am trying to collect all of the records for the US and have not had success in New York.

Jane,

I have not had luck finding the records in New York but I have not given up. I really believe that these records are packed away and forgotten in either the NYC Municipal Archives or in the NYS Archives. I will post on this site if I ever find them.