The abandoned property dilemma

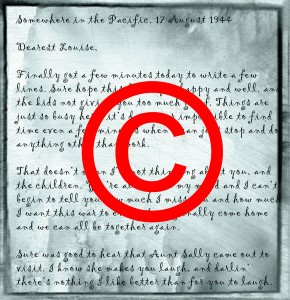

A reader bought a box at a local flea market and was enchanted to find that it contained letters — more than 100 letters — written during World War II by a Seabee to his girlfriend.

The Seabee made it home safely after the war, and the girl he was writing to later became his wife. They lived locally for the rest of their lives, and the reader was able to find their obituaries. So the letters can’t be returned… but could they be published?

The Seabee made it home safely after the war, and the girl he was writing to later became his wife. They lived locally for the rest of their lives, and the reader was able to find their obituaries. So the letters can’t be returned… but could they be published?

At the same flea market, the reader also found old ledgers from a no-longer-active Rebekah chapter. (Rebekahs are the women’s arm of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.1) The ledgers have significant local historical interest, listing people and information who were active in the community, and maybe the local historical society would be able to make good use of them.

Both of these finds, as exciting as they were, raised tough questions in the mind of the reader, who puzzled over them and then tossed them over to The Legal Genealogist:

I was wondering what sort of laws might come into play if these (letters) were published. …

I was considering perhaps donating (the journals) to the historical society but … was asked if I would sign something that I had legal rights to them, knew where they came from, etc. etc.. There was not an option to say ‘bought them at a flea market’… Therefore they are still sitting in a box in my basement.

So the question is really as you find things that reflect ancestors that are not your own are there restrictions on their use?

The simple answer here is yes, there are restrictions. That doesn’t mean you can’t make any use of the materials, but it does mean that you’ll need to think through the pluses and minuses, the benefits and the risks, of the uses you have in mind.

Copyright basics

Let’s go over some basics first.

First and foremost, we need to remember what’s eligible for copyright protection and what isn’t. Copyright law protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.”2 That definition doesn’t include “facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed.”3

Second, we need to understand that owning specific physical items — those letters, the Rebekah chapter journals — is entirely separate and apart from owning any copyright there may be in the items. The U.S. Copyright Office explains that:

Mere ownership of a book, manuscript, painting, or any other copy or phonorecord does not give the possessor the copyright. The law provides that transfer of ownership of any material object that embodies a protected work does not of itself convey any rights in the copyright.4

Clearly, the reader here is the legal owner of these items. They were bought, fair and square, after being given away or sold or somehow abandoned. But owning the items themselves doesn’t affect ownership of the copyright.

Third, the fact that the Seabee’s family or the Rebekah chapter let these things end up at a flea market doesn’t have any effect on the copyright protection they get. Because ownership of the thing is separate from ownership of the copyright, abandoning the thing doesn’t mean abandonment of the copyright. The law on this couldn’t be clearer:

“In copyright, waiver or abandonment of copyright ‘occurs only if there is an intent by the copyright proprietor to surrender rights in his work.'” A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc., 239 F.3d 1004, 1026 (9th Cir. 2001)…. Abandonment of a copyright “must be manifested by some overt act indicative of a purpose to surrender the rights and allow the public to copy.” Hampton v. Paramount Pictures Corp., 279 F.2d 100, 104 (9th Cir. 1960).5

So the issue here on both of these items really is a garden-variety copyright issue. Were the letters and the journals ever copyrighted? If they were, are they still copyrighted today? If they are, then who owns the copyright?

The letters

Copyright as to the letters is an easy question. Because they were “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,”6 and because the letters were never published, the letter writer had full copyright protection on them. Under the 1976 U.S. Copyright Act as amended to today,

Works originally created before January 1, 1978, but not published or registered by that date… have been automatically brought under the statute and are now given federal copyright protection.7

Copyright in unpublished works lasts for 70 years after the death of the creator.8 Now basic math is not my strong point, but even I can subtract 70 from 2012: for those letters to be out of copyright, the Seabee would have had to die in 1942. Since that didn’t happen, those letters are still protected.

So you have two choices. One is to use only the smallest portions of the letters that might qualify under what’s called the fair use doctrine. That’s set out in federal law at 17 U.S.C. § 107, which provides that:

the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means …, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include –

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Chances are, you’d be okay if you published bits and pieces. In reality, if the family thought so little of these letters that they let them go at a flea market, chances are you’d be okay if you published them all. (I’m not suggesting that, just commenting on the realities of the situation.)

But there is, of course, a better way:

Ask for permission.

Sounds easy, until you start wondering who you would have to ask. “Ownership of a copyright . . . may be bequeathed by will or pass as personal property by the applicable laws of intestate succession.”9 That means, simply, that whoever has the rights to the Seabee’s estate owns the copyright to those letters too.

The possibilities are:

• The Seabee left a will, left his personal property to someone in particular, and that someone is still alive. That person is the copyright owner and his or her permission is all you need.

• The Seabee left a will, left his personal property to someone in particular, and that someone isn’t alive today. You’d need to find out who that person’s estate went to — by will or by intestacy — because the copyright would have been part of that estate.

• The Seabee didn’t leave a will, so his estate went to his heirs-at-law under the laws of your state. That means, of course, you’ll need to figure out who his heirs-at-law were. If he outlived his wife, you only need to trace his side. But if he died first, and state law gave part of his estate to his widow and part to his heirs, you may need to trace both sides.

But hey… we’re genealogists, right? We should be able to find the heirs… and it might be fun to try.

The Rebekah journals

The Rebekah journals are a bit more problematic. The hitch here is that they may not qualify for copyright protection at all. Again, you only get copyright protection on something if it has some basic element of originality or creativity. A journal that simply lists dates and places and memberships — in other words, a recitation of facts — may well not qualify for copyright protection.

But if the journals do have some prose descriptions, some even small creative spark, you’re better off erring on the side of caution and assuming that they were copyright-protected as unpublished documents just as those letters were.

And you’d be well advised to treat them as works of corporate authorship, and that means they’re protected for 120 years after the records were created.

Now you can still use any of the facts from these journals without having to try to find anybody that you can ask for permission. Facts, again, can’t be copyrighted. It’s only if you wanted to copy whole segments of the journals or make digital images and the like that you’d need to worry about asking anybody.

What makes them a little easier than the letters, though, is that there is somebody who’s easy to find to ask for permission: the national Rebekahs. The national organization is the natural successor in legal interest to the local chapter, and there’s a Contact Us link at the top of the website for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows.

Bottom line

It’s always a good idea to stop and think about copyrights and usage permissions any time you come across original works by a third party. Though using portions of both of these types of records should be safe, it’s safer still to follow that simple rule:

Ask for permission.

And at least we, as genealogists, are better-equipped than most researchers to find the people we’d need to ask!

SOURCES

- See “Rebekahs,” IOOF (http://ioof.org : accessed 2 Dec 2012). ↩

- 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, “Copyright in General: What does copyright protect?,” Copyright.gov (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 2 Dec 2012). ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, PDF version at p. 2 (http://www.copyright.gov : accessed 2 Dec 2012.) ↩

- Melchizedek v. Holt, 792 F. Supp. 2d 1042, 1051 (D. Ariz. 2011). ↩

- 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). ↩

- U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 1: Copyright Basics, PDF version at p. 5. ↩

- For a chart outlining the basics of copyright duration, see Judy G. Russell, “Copyright and the old family photo,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 6 Mar 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 1 Dec 2012). ↩

- 17 U.S.C. § 202(d)(1). ↩

Have you written the book yet, Judy? That book called something like …”It’s The Law! Genealogy and Legal Issues” -? I’m learning. It’s getting clearer and clearer. Thanks for posting such useful information! Cheers.

Sure, I’m writing it… it’s what I do in my “abundant” spare time…

I am currently in the process of blogging about the letters my grandparents wrote to each other during World War II. I am in possession of the letters (around 500 of them) and have been for the last decade. My father saved them for me when he was moving his mother into a nursing home. As my father was the direct heir of my grandparents and I am my father’s heir, I would assume that I also own the copyright to the letters at this point. What is your opinion?

Yes, but… (You knew that was coming, right?) The only hitch is if there are other heirs whose permission you should get. If you’re the only child of your father and he was the only child of your grandparents, you’re good to go. If your father had siblings, you should let your aunts and uncles (or their heirs, presumably your cousins) know what you’re planning. If you have siblings, you should let them know.

I have notified all the relatives that I can think of that I am doing this. Sadly, I have gotten little acknowledgement (or replies) to my emails and messages. I have one brother and 3 cousins (one of which is deceased so theoretically her two sons would also be heirs). I have contacted my aunt (who would presumably tell her children) as well as sent several emails to one of my surviving cousins.

At least they’re not saying no — or doing what my relatives usually do… rolling their eyes!

I’m sure they are rolling their eyes behind their computer screens. 🙂

🙂

I told my aunts and uncles that I was going to put my grandparents’ WWII letters into a book. My sister was executor for my aunt’s estate, who had the letters in her closet. She said go for it. Everyone (especially my distant cousins) were happy to get a copy of finished book (Camp Letters: 1942 – 1945). The alternative would have been to break up the collection. The copyright wasn’t much of an issue. I’ve never sold enough copies to cover my costs. It was truly a labor of love.

As long as all the heirs are in agreement, this won’t ever be an issue.

My Great-Aunt gave me some moth eaten letters and a telegram that had belonged to her Aunt Gladys, which had been written by Gladys’ step-daughter, Edith. Edith was a somewhat well known actress in the 1940s and the letters were pretty interesting. I made copies, but ultimately felt that the letters belonged to the family of the now deceased Edith. My feelings were based on personal ethics, but I figured the copyright would align with that (and now I know!). I was able to track down Edith’s granddaughter on Facebook and send her the letters.

A very good — legal and ethical — choice here, Valerie.

Judy – I love reading and learning from your articles! Not only do I learn from the material you post but I learn by seeing your excellent format style, footnote methodology, and quality references! Does the software you use for your blog which looks like WordPress have a true footnote feature like the one in Microsoft Word? I started blogging using Weebly and as I try to source my material in a quality manner, I realize that this may not be the right tool as it does not have a footnote feature or the ability to use a superscript (which still wouldn’t be a good use of time). Hoping to learn how you selected WordPress so I can switch to a tool that had a better tool to source my SHACKFORD resources. Thanks again for setting such high standards for sourcing –it really helps those of us starting out.

First off, thank you so much for the kind words, Joanne!

The thing I like best about WordPress is that somebody has already figured out how to do just about anything I might want to do, and written a plug-in to do it. I use a little footnote plug-in called FD Footnotes. It’s not the same thing as you’d see in a word processing program like Word. Instead, you put the footnote into brackets where it would go. The plug-in then inserts the superscripted number and puts the footnote where you want it at the bottom of the post. There are some drawbacks — you have to use parentheses where you might otherwise use brackets! — but it sure works well for me.

Since your correspondent owns the physical letters and journal, couldn’t s/he donate or sell them to the historical society? S/he could write something about the provenance but not claim s/he owned the copyright to them. Do historical societies only take items where the copyright title is clearly transferred to them?

She absolutely could donate them if the historical society agrees, Randy. That’s why I was emphasizing that she is the legal owner — she certainly does have the right to transfer that legal ownership to the historical society. Most societies ask about provenance but, in my experience, most don’t insist on copyright title — they couldn’t even accept a donated book if they did!

Hi Judy,

I was wondering if the same copyright laws would apply to the handwritten messages on historical postcards? Also, what are the laws in regards to publication of historical real photo postcards and historical postcards featuring artistic designs?

Thanks!

Yep, Talea, exactly the same laws apply. The handwritten messages would be copyright to the writers, and the postcards to their creators. The one difference is that the messages would likely be considered unpublished (longer copyright time, 70 years after the death of the writers) while the postcards themselves should be considered published (obviously created to be sold, and offering for sale constitutes publication under the copyright laws, so a different time line would apply). Check out the chart here to see what the requirements would be for the copyrights.

Thanks Judy!

I appreciate the confirmation. The chart is a huge help as well!

Best Regards!

Glad to help!

Remember that underlying facts are not protected, so you can use the information in the journal without risk of copyright infringement, it is expression, that is the specific wording or phrases, that may be protected.

Yep, says so in the blog post: First and foremost, we need to remember what’s eligible for copyright protection and what isn’t. Copyright law protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” That definition doesn’t include “facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed.”

I have copies of old family letters written in the 1800s. The location of the originals is unknown. Another family member transcribed and published these letters in a book in 1979. She also had only copies of the letters. Does the author of the book have the copyright to these letters (she was not the heir)? If not, am I allowed to publish these on my genealogy blog if I use my own transcription?

Thank you!

The family member does NOT have the copyright if she was not the heir, and the letters themselves are out of copyright as long as the writer died more than 70 years ago. If that’s the case, anyone can publish the letters with his/her own transcriptions.

Thank you so much for this invaluable information. I am also in possession of unpublished personal letters written from 1861-1867 that have been passed down through our family written to my GG Aunt. I wish to donate them to the Library of Congress and the LOC has agreed to accept their donation. As they are out of copyright (70 years after the author died – he passed in 1878) do I have any copyright responsibility to preserve for any other heirs?

No. Once copyright expires, no-one (heir or not) has any copyright claim.

I have saved forty five years’ worth of personal letters written to me from a lot of Interesting people. I fthink the letter writing process, the content, and the historical significance of these letters, would make a fascinating story about friendship and love, and the closeness people often felt and expressed though their penned words. I have read your legal advice, and wonder if I do not publish the authors’ names, and omit specific details that might allow the authors to recognize their sentiments, would I then be safe to do so?

No easy answer to this, Deb — but let me pose a question: what is the reason why you would not ask the letter writers for permission to use the letters?

Hello-I have World War 2 V-Mail letters that I would like to display in a museum exhibition. Do I have to have copyright permission to do this? If I decide to published them in a catalog, but do not charge anything for the catalog (free to the public), do I have to have copyright permission. The catalog would be for educational purposes only-no profit would be made. Thanks-Pat

Nobody except an attorney licensed in your jurisdiction can advise you for certain. I can tell you that it’s always safest to get permission if the letters are still copyright-protected (if the author died within the last 70 years, they could be), but that you can always do a fair use analysis. Bottom line is that talking to a local lawyer is your best bet.

What about a poem was written by a deceased loved one, giving them credit for the poem. Can this be placed inside an autobiography, given credit to the writer, without permission, since she has since passed?

Copyright lasts for 70 years after death, so the mere fact that the person has died does not end the copyright or the requirement to get permission. The copyright to the poem is owned by the authors’ heirs for the 70 years after death.

My ancestor was institutionalized from 1923 – 1930. During this time, she and her mother wrote many letters back and forth. All letters were kept by the Superintendent of the institution. The place was closed in the mid 1990’s and abandoned by the State of RI, leaving all records inside. During the next decade, the property was vandalized and records and other “souvenirs” were stolen. An author has put together an epistolary novel documenting three women who were inmates. One of these is my ancestor who died in 1972. While the family is grateful to have the information contained in the letters that we normally would never have been given access to, by reading your blog post, it seems the author had no right to use these letters without permission of her heirs. The author did change her surname, but included her DOB and an address that can be verified as hers via a census record… Am I correct that this is copyright infringement as the author of (some of) the letters has not been deceased for over 50 years?

The novelization of the information might shift it into being what’s called a transformative use, and that could be a fair use under the copyright laws. You’d need to consult with an attorney licensed in your jurisdiction to see whether it’s sufficiently different to qualify. More significant is the invasion of privacy of your ancestor. Using her actual date of birth and address leads directly to identification, and that’s much more of a problem. Again, you need to consult with a lawyer licensed in your jurisdiction if you want to take any action here.

I am working on a large art project painting World War 2 letters to look like they are folded up into origami peace cranes. Each crane is surrounded by monarch butterflies – as if the love expressed in the letter is the nectar attracting the butterfly. I will be including 72 letters in the project, one per month of the war, each painted to look like a crane. Do I need permission from each heir to all 72 letters to include them in this project considering I am only using small sections of the letter on sections of the origami crane? Does it change the copyright if I am using them to create something completely new – as in a painting?

Keeping in mind my usual caveat that this-is-not-legal-advice and you-need-to-consult-with-an-attorney-licensed-in-your-jurisdiction, my own take on this would be that (a) using small portions of letters for (b) the creation of an entirely different type of artistic work would be both fair use and transformative use, both of which are exceptions to the general rule. BUT… seriously… this is not legal advice.