The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

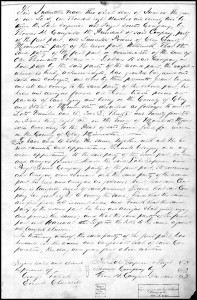

On the sixth day of June, 1872, Lauriston Powers of Clay County, Minnesota, became the owner of four lots in the newly-laid-out Town of Moorhead. He paid a total of $1,000 for lots one, two, three and 24 in block 48, “according to the Plat of said Town filed for record in the County of Clay Minnesota.”1

Moorhead — platted in 1871 and bordered to the west by the Red River of the North and Fargo, North Dakota2 — was one of many many towns that sprang up alongside the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad.The seller, the Lake Superior & Puget Sound Land Company, was set up to buy lands all along the surveyed route for the Northern Pacific Railroad and lay out, plat and advertise the towns along the tracks.3 It sold thousands of lots to individual buyers like Powers.

Powers must have held onto the land for a while — there’s no record of his name as a grantor in the Clay County index during the decade that follows4 — but there’s no Lauriston Powers in the 1880 census in Clay County.5

He may well have been a speculator and he may have gone down in the Panic of 1873, kicked off in large measure by the collapse of Cooke & Company, the bank that ended up owning much of the Northern Pacific Railroad.6

But Powers knew enough, and so did other buyers in those early days of Clay County, to make sure there was specific language in his deed — promises by the seller of the land, promises called covenants of title.

Powers’ deed had most of the usual covenants. In particular, the deed said, the seller “does covenant … as follows:”

First, that said Company is lawfully seized of said premises;

Second, that said Company has good right to convey the same;

Third that the same are free from all incumbrances, and

Fourth that the (buyer) shall quietly enjoy and possess the same; and

that the said (seller) will Warrant and Defend the title to the same against all lawful claims.7

That first promise, that the seller was “lawfully seized of said premises,” is called a covenant of seisin, and it was an “assurance to the purchaser that the grantor has the very estate in quantity and quality which he purports to convey.”8

The second promise, that the seller had “good right to convey the same,” is called a covenant of right to convey, and it was an “assurance by the covenantor that the grantor has sufficient capacity and title to convey the estate which he by his deed undertakes to convey.”9

The third promise, that the premises were “free from all incumbrances,” is called a covenant against incumbrances, and it was a promise that the land wasn’t subject to any claim, lien, liability or mortgage in favor of anyone else.10

The fourth promise, that the buyer would be able to “quietly enjoy and possess” the land, is called a covenant for quiet enjoyment, and it didn’t mean the buyer would hear nothing but the birds chirping. Instead, it was an “assurance against the consequences of a defective title, and of any disturbances” based on the title to the land.11

And the fifth and final promise, that the seller would “Warrant and Defend the title to the (land) against all lawful claims,” is called a covenant of warranty, and it was an “assurance by the grantor of an estate that the grantee shall enjoy the same without interruption by virtue of paramount title” (meaning a superior title, one that could defeat the title conveyed).12

There’s a sixth general covenant you’ll see sometimes, called a covenant for further assurance, a promise by the seller to do whatever is necessary to make sure the title conveyed to the buyer is perfected.13 Powers didn’t get that one in his deed; it doesn’t seem to have been standard in the deeds at that time and in that place.

All of these covenants taken together are called covenants for title,14 and they’re usually set out in the terms of the deed itself. But sometimes you’ll just see a deed called a warranty deed or a general warranty deed; using that term in the deed carries with it at least the promise that the seller actually owned the title he was selling.

By contrast, if you see the term “quitclaim” in a deed, that’s different. That only sells whatever interest the seller had — if he had anything at all.15

So always look for those promises in deeds, from time periods both earlier and later — and if you’re a home- or landowner yourself, you’ll even see them in your deed today.

Um… well… At least you’d better hope you see them in your deed today…

SOURCES

- Clay County, Minnesota, Deed Book A : 3, Lake Superior & Puget Sound Land Company to Powers, 6 Jun 1872; County Register of Deeds, Moorhead; digital images, “Clay County Land and Property Records, 1872-1947,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed 16 Dec 2012). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Moorhead, Minnesota,” rev. 16 Dec 2012. ↩

- Hiram Carleton, ed., “Thomas Hawley Canfield,” Genealogical and Family History of the State of Vermont (1903) (Baltimore, Md. : Genealogical Pub. Co., reprint 1998), 395. ↩

- Clay County, Minnesota, Grantor Index, 1873-1888, vol. 1, M-Z; County Register of Deeds, Moorhead; digital images, “Clay County Land and Property Records, 1872-1947,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed 16 Dec 2012). ↩

- A search was conducted of all of the Moorhead listings in the 1880 United States Federal Census database at Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 16 Dec 2012). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Jay Cooke & Company,” rev. 9 May 2012. ↩

- Clay Co., Minn., Deed Book A : 3, Lake Superior & Puget Sound Land Company to Powers, 6 Jun 1872. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 297, “covenant of seisin.” ↩

- Ibid., 297, “covenant of right to convey.” ↩

- Ibid., 297, covenant against incumbrances. See also ibid., 613, “incumbrance.” ↩

- Ibid., 297, “covenant for quiet enjoyment.” ↩

- Ibid., 297, “covenant of warranty.” See also ibid., 867, “paramount.” ↩

- Ibid., 297, “covenant for further assurance.” ↩

- Ibid., 298, “covenants for title.” ↩

- Ibid., 986. “quitclaim deed.” ↩

Nice, very nice, Judy. Making more sense to see those interesting phrases on deeds. And don’t you love that old word ‘seisin’ -?

You just have to love those old words, Celia! Tis the season for seisin!