Three bills to affect SSDI access

Even with the constant crisis news out of Washington, D.C. — “the fiscal cliff is going to ruin the economy!” “the sequester is going to ruin the economy!” “Congressional gridlock is going to ruin the economy!” — members of Congress have taken the time to take public access to the Social Security Death Master File (what we know as the Social Security Death Index or SSDI) and put it into their gunsights in this now-six-week-old legislative session.

We’re now up to three bills, all in the House of Representatives, that would restrict access to the SSDI or to information on the SSDI. And one of ’em is a new type of threat to access.

We’re now up to three bills, all in the House of Representatives, that would restrict access to the SSDI or to information on the SSDI. And one of ’em is a new type of threat to access.

The first bill to be introduced was H.R. 295, the “Protect and Save Act of 2013,” introduced by Rep. Richard Nugent (R-Florida). That bill would close the SSDI for up to three years after a person’s death to everyone except those certified to have “a legitimate fraud prevention interest in accessing the information.”1

The latest bill introduced in this new session of Congress is H.R. 531, the “Tax Crimes and Identity Theft Prevention Act,” sponsored by Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Florida) and co-sponsored by Nugent. And it would close the SSDI for up to two years after a person’s death to everyone except those certified to have “a legitimate fraud prevention interest in accessing the information.”2

Both of these take the same basic approach as most of the legislation introduced in the last Congressional term — close the records for a while except to those who work in fraud prevention. And most genealogists could live with that. For most of us day-to-day family researchers, we just don’t need instant access to the SSDI.

But that’s not true for all of us. Because there are genealogists who do need that kind of access — genealogists who work to identify military remains, who work with coroners’ offices and medical examiners, who are forensic genealogists, heir researchers, and those researching individual genetically-inherited diseases.

And they are not among those who could be certified to have “a legitimate fraud prevention interest in accessing the information.” Their work — work that all of us as a society should be supporting and assisting — would be horribly impacted. Loss of this resource would be devastating.

So as much as most genealogists would like to find common ground with members of Congress who are concerned about identity theft, we’re unable to support bills like these. They paint with far too broad a brush.

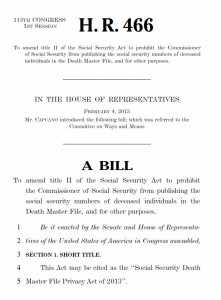

And that brings me to the third bill of the 113th Congress. H.R. 466, the “Social Security Death Master File Privacy Act of 2013.” Introduced by Rep. Michael E. Capuano (D-Massachusetts), it would bar any access by any member of the public to the social security account number of any deceased person — no matter how long ago that person died:

(i) The Commissioner of Social Security may not publish in the Death Master File (or any other public database maintained by the Commissioner that contains information relating to the death of individuals) the social security account number of any deceased individual.

(ii) The Commissioner shall not be compelled to disclose the social security account number of any deceased individual to any member of the public …3

That’s deceptively simple, isn’t it? Everybody can have access to the SSDI but not to the social security numbers, and why would anybody need social security numbers of dead people anyway?

Sigh… let me count the ways. For starters, all those fraud prevention folks — remember them, Rep. Capuano? — need access to both the name and the social security number so that identity thieves can’t use the number of some deceased person to open credit accounts or file a fraudulent tax return. Having part of the information doesn’t help a whole lot if what you’re trying to do is prevent fraud. Just read Dick Eastman’s post today — here — to see why this whole approach is wrong.

And why do we as genealogists need access? Well, maybe we don’t if the person we’re researching was named Hennypenny Johnjacobjingleheimerschmidt and there’s only ever been one in any of the records. But if the person we’re researching is John Jones or Matthew Johnson or Martin Baker (all names in my own family tree), I daresay having the number to distinguish one John Jones from another might be a tad useful.

Now — fortunately or unfortunately for the country as a whole, watching the gridlock in Washington as one fiscal crisis after another approaches — it does seem that this Congress is a bit distracted these days so these bills aren’t being fast-tracked for quick action so far. But they could be, at any time. And we’re going to have to be ready to speak out if that should happen.

Stay tuned…

SOURCES

- § 7, H.R. 295, 113th Congress, 1st sess., Congress.gov (http://beta.congress.gov : accessed 24 Feb 2013). See also generally Judy G. Russell, “News from the SSDI front,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 20 Jan 2013 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 24 Feb 2013). ↩

- § 12, H.R. 531, 113th Congress, 1st sess., Congress.gov (http://beta.congress.gov : accessed 24 Feb 2013). ↩

- § 2, H.R. 466, 113th Congress, 1st sess., Congress.gov (http://beta.congress.gov : accessed 24 Feb 2013). ↩

His name is my name, too.

Whenever we go out,

The people always shout,

“There goes John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt!”

I’m glad SOMEBODY recognized the reference, Eric! (And I have a Johann Jacobus Smidt in my line… so…)

I thought your title was a reworded reference to Genesis’s “…And Then There Were Three” album!

🙂

Many individual companies also check the Social Security numbers of new hires against the SSDI. Social workers use the SSDI to track family members, just as genealogists do.

There are many people who NEED that access who don’t fall into the “fraud prevention” category. I don’t understand why that’s so hard for the Congresscritters to understand.

I wonder what would happen to life insurance companies who are required at the state level to use the SSDI. I am unsure if searching the SSDI for someone who recently is deceased would fall under fraud prevention even if it is mandated by the state. I live in Kentucky where there just happens to be just such a requirement.

I believe that an insurance company, by the very nature of its business, would have a legitimate fraud prevention need for the information (paying claims only in cases of actual death and only to verifiable beneficiaries).

There needs to be an organized effort to vote against the people that introduce this type of law.

That movement has to come from each of us, Ed. Nobody else is going to do it.