Johnson’s acquittal

One hundred and forty five years ago today, it was Judgment Day in the United States Senate. And the odds were against the man on trial.

There were 27 states then represented in the Senate — the former Confederate States weren’t yet voting again — and a two-thirds vote was needed. Just 36 Senators had to vote yes, and Andrew Johnson would have been removed as President of the United States.

The Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Salmon Chase, had presided over Johnson’s trial in the Senate and it fell to him to poll the members when, on this day, 145 years ago, the first and decisive vote was taken on the most likely of the 11 articles of impeachment to succeed.1

The Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Salmon Chase, had presided over Johnson’s trial in the Senate and it fell to him to poll the members when, on this day, 145 years ago, the first and decisive vote was taken on the most likely of the 11 articles of impeachment to succeed.1

It all came down in the end to one man, Senator Edmund Gibson Ross of Kansas. He was born in Ashlasnd, Ohio, 7 December 1826, raised in Ohio and apprenticed there as a printer. He moved to Wisconsin in 1849 and to Kansas in 1856.2

Most of his career was spent in the newspaper business. He’d worked with the Milwaukee Sentinel, published the Topeka Tribune, founded the Kansas State Record, and edited the Kansas Tribune. A Civil War veteran, he was appointed to the Senate to fill the seat vacated by the death of Sen. James Lane in 1866.3

He was defeated when he ran for a full term in 1870, defeated as a candidate for Kansas Governor in 1880 and held only one additional political job in his life — he was appointed Governor of the Territory of New Mexico in 1885 and serrved for four years.4

Like so many members of the Senate, Ross had been widely lobbied by both sides in the impeachment fight. But no-one knew for certain how he would vote when the time came. Historian David Dewitt was there when Ross was called upon to cast that key vote:

Thirty-six votes are needed, and with this one vote the grand consummation is attained, Johnson is out and Wade in his place. It is a singular fact that not one of the actors in that high scene was sure in his own mind how his one senator was going to vote, except, perhaps, himself. “Mr. Senator Ross, how say you?” the voice of the Chief Justice rings out over the solemn silence. “Is the respondent, Andrew Johnson, guilty or not guilty of a high misdemeanor as charged in this article?” The Chief Justice bends forward, intense anxiety furrowing his brow. The seated associates of the senator on his feet fix upon him their united gaze. The representatives of the people of the United States watch every movement of his features. The whole audience listens for the coming answer as it would have listened for the crack of doom. And the answer comes, full, distinct, definite, unhesitating and unmistakable. The words ‘Not Guilty’ sweep over the assembly, and, as one man, the hearers fling themselves back into their seats; the strain snaps; the contest ends; impeachment is blown into the air.5

Exciting historical times, for sure, and part and parcel of what we as genealogists want — and need — to consider in our family histories. Our job isn’t just to record the names and dates and places, but the stories of our people and their times. The BCG Standards Manual calls on us to consider “the data’s background context…, including … the literature, laws, regulations, customs, and history of the area, time period, population group, and government or military jurisdiction.”6

Consider, if you will, the people touched by this one event, this one day, in the United States Senate.

Clearly, those whose family line intersects that of Andrew Johnson already have this pivotal historical event in their family histories (or they should!). But then there are the 54 Senators who cast votes whose family lines may join with ours in one way or another:

• To convict: Anthony (RI), Cameron (PA), Cattell (NJ), Chandler (MI), Cole (CA), Conkling (NY), Conness (CA), Corbett (OR), Cragin (NH), Drake (MO), Edmunds (VT), Ferry (CT), Frelinghuysen (NJ), Harlan (IA), Howard (MI), Howe (WI), Morgan (NY), Morrill (ME), Morrill (VT), Morton (IN), Nye (NV), Patterson (NH), Pomeroy (KS), Ramsey (MN), Sherman (OH), Sprague (RI), Stewart (NV), Sumner (MA), Thayer (NE), Tipton (NE), Wade (OH), Willey (WV), Williams (OR), Wilson (MA), Yates (IL).7

• To acquit: Bayard (DE), Buckalew (PA), Davis (KY), Dixon (CT), Doolittle (WI), Fessenden (ME), Fowler (TN), Grimes (IA), Henderson (MO), Hendricks (IN), Johnson (MD), McCreery (KY), Norton (MN), Patterson (TN), Ross (KS), Saulsbury (DE), Trumbull (IL), Van Winkle (WV), Vickers (MD).8

Add to those Chief Justice Salmon Chase, and all of the members of the House of Representatives who had voted for — or against — the articles of impeachment on which Johnson was tried.

Then add the managers from the House who presented the case against Johnson in the Senate, including John A. Bingham of Ohio, Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts, and Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania. And the Presidebntial defense team, including “former Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Curtis; William Evarts, a prominent Republican lawyer; and Henry Stanbery, a former Attorney General in Johnson’s cabinet.”9

Add all the people who worked for the Congress or at the White House, the pages, the clerks. Add those who came to Washington to watch part of the trial. Add those who followed the events in the newspapers. Add, in fact, everyone alive and paying attention to national news — or even affected by it — in 1868.

History and events like these add so much to what we know, and hope to understand, about our ancestors.

SOURCES

- See generally Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Impeachment of Andrew Johnson,” rev. 14 May 2013. ↩

- “ROSS, Edmund Gibson, (1826 – 1907),” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (http://bioguide.congress.gov/ : accessed 15 May 2013). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- David Miller Dewitt, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson, Seventeenth President of the United States (New York : MacMillan, 1903), 552-553; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 15 May 2013). ↩

- Board for Certification of Genealogists®, The BCG Genealogical Standards Manual (Washington, D.C. : BCG, 2000), Standard 23 at 10. ↩

- The Congressional Globe, Special Supplement: The Proceedings of the Senate Sitting for the Trial of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States (Washington D.C. : Rives & Bailey, Printers, 1868), 411; digital images, “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 15 May 2013). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Research Guide on Impeachment,” “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875,” Library of Congress, American Memory (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html : accessed 15 May 2013). ↩

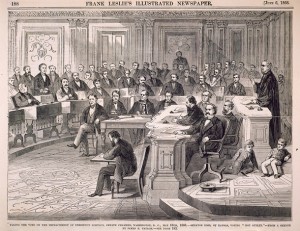

You do tell a good story, Judy. And this one was very exciting for both historical and genealogical reasons. The detailed sketch above has so much happening in it as well. Thanks for sharing this fascinating story.

Thanks for the kind words, Celia!

Judy, there may be no way to know this, but I’m fascinated by the drawing. Is this an actual scene from the proceedings or just a contrived picture after the fact? Does anyone have an actual identification of the persons pictured? Who are the two boys sitting next to the judge’s bench? Are they actually someone’s sons or are they representative of some characteristics? Why is the judge standing? In my limited court room experience, the judge walks into the court and takes his/her seat while everyone else is standing, the departure is likewise, and the judge never stands during the proceedings. Just curious.

I’m sure it was sketched at the time, Mary Ann, much as newspaper and television artists do now when photography isn’t permitted. With a seating chart in the chamber we could probably reconstruct who was who. I was thinking, as you do, that Chief Justice Chase was seated as each senator rose and cast his vote, but I can’t be sure. The contemporary account by David Dewitt says: “…the Chief Justice rises, grasps the sides of the desk before him and utters the words, ‘Call the roll.'” So he may have been standing. And the boys? Pages. They ran errands fior the members of Congress. We still have Congressional pages today, though they’re teenagers, 16-18 usually.

But perhaps the person with the most to gain, or fear, was the presumptive successor – was it Senator Wade of Ohio who voted “Guilty?” Or another Wade who was speaker of the House?

This would have been the first time a Speaker ascended to the Presidency, and the first conviction of a President.

I think the Judge was standing because it was the deciding vote and he wanted to hear it clearly and then command the scene if Johnson was found guilty.

Actually (and there’s a whole ‘nother post for the future on Presidential succession), the law was different then. The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, simply provides that the Vice President will succeed the President and what happens after that is up to Congress. The first Succession Act, of 1792, made the next in line the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, followed by the Speaker of the House. That wasn’t changed until 1886 when Congress took its own officers out of the line of succession and put in the President’s cabinet, starting with the Secretary of State. That was changed again in 1947, when the Congressional officers were put back in before the Cabinet members, but with the Speaker first before the President Pro Temp of the Senate. So at the time it was in fact Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, who voted to remove Johnson, who would have become President if the vote had gone the other way.

thanks, I forgot that “it’s not always been the way it is now.”

Yeah, our ancestors were always playing games with our minds by changing the laws like that! Silly rabbits!

Loved this one Judy! Such a good story. This paragraph out of the post is critical to the whole point — MHO, OC.

That’s the key, for sure, Lynda! It’s the only way we can do justice to our ancestors — to put them into the context of their times.

A watershed event. History would have been different if Johnson had been removed.

Absolutely — but it’s hard to know just how it would have changed. The Radical Republicans did have quite a strong voice even without being able to remove Johnson.