The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

The law was approved on the 24th of January 1839. It was one of the first passed by the First Session of the Legislative Assembly, held at Burlington, in what was then the Territory of Iowa.

And, the Territorial Legislature decreed:

And, the Territorial Legislature decreed:

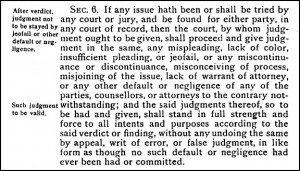

If any issue hath been or shall be tried by any court or jury, and be found for either party, in any court of record, then the court, by whom judgment ought to be given, shall proceed and give judgment in the same, any mispleading, lack of color, insufficient pleading, or jeofail, or any miscontinuance or discontinuance, misconceiving of process, misjoining of the issue, lack of warrant of attorney, or any other default or negligence of any of the parties, counsellors, or attorneys to the contrary notwithstanding; and the said judgments thereof, so to be had and given, shall stand in full strength and force to all intents and purposes according to the said verdict or finding, without any undoing the same by appeal, writ of error, or false judgment, in like form as though no such default or negligence had ever been had or committed.1

Jeofails.

Right. Sure. Anything you say.

I mean, seriously, even The Legal Genealogist — a genealogist with a law degree! — had never ever before even heard of the word “jeofails,” much less seen it used in a statute.

So, of course, I did what any self-respecting genealogist with a law degree would do.

I looked it up.

Black’s Law Dictionary spells the word “jeofaile” and defines it as “an error or oversight in pleading.” And it then quotes an earlier dictionary by John Rastell with a longer explanation:

Jeofaile is when the parties to any suit in pleading have proceeded so far that they have joined issue which shall be tried or is tried by a jury or Inquest, and this pleading or issue is so badly pleaded or joined that it will be error if they proceed. Then some of the said parties may, by their counsel, show it to the court, as well after verdict given and before judgment as before the jury is charged. And the counsel shall say: “This inquest ye ought not to take.” And if it be after verdict, then he may say: “To judgment you ought not to go.” And, because such niceties occasioned many delays in suits, divers statutes are made to redress them.2

Aha! Light begins to dawn. So if you ever run across this, in an old court record or, as here, in a statute book, here in plain English is what’s going on.

Once upon a time, the law courts were really sticky in how you prosecuted or defended a case. The courts spent a lot more time overall looking at the way you wrote (or spoke) your pleading than in seeing that justice was done. As Black’s makes clear, pleading was a

peculiar science or system of rules and principles, established in the common law, according to which the pleadings or responsive allegations of litigating parties are framed, with a view to preserve technical propriety and to produce a proper issue.3

But sometimes nobody figured out that the way you wrote your pleading wasn’t exactly right until the case was well underway — and sometimes not even until the case was completely finished. And, you can imagine, sometimes a canny lawyer would figure out that the other side had blown it somehow and would sit back and wait to see if he lost the case. Then if he did lose, he’d pounce by revealing the pleading problem then.

That was the “jeofail.” And, strictly speaking, a judge confronted with that technical problem in the paperwork wasn’t supposed to wrap up the case by entering judgment for the winning side.

Unless, of course, the law said he could… and the way the law said he could was a law exactly like the one Iowa passed at its very first territorial legislative session — authorizing its judges to go ahead and enter the judgment for the party who won at trial and telling its appeals courts not to overturn a judgment on appeal just because of some technical problem with the paperwork.

So if you run across the word “jeofail,” now you know what it means. And why it mattered. And what the law did to fix it.

Jeofail.

Sounds like a winner to me.

SOURCES

- § 6, “An Act Concerning Amendments and Jeofails,” in The Statute Laws of the Territory of Iowa, Enacted at the First Session of the Legislative Assembly of Said Territory, Held at Burlington, A.D. 1838-’39 (1839; reprint, Des Moines : Historical Department of Iowa, 1900), 46; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 26 Jun 2013). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 649, “jeofaile.” ↩

- Ibid., 902, “pleading.” ↩

This is great! I shall incorporate the word jeofail into my vocabulary!

Isn’t it a fun word? I believe it’s pronounced JEFF-ail.

Oh the places you go, Judy! From old French… Whew! My brain buzzes with how to use this word now. I can see that the past with my 4 challenging teenagers would have been a great time to use it!

You can always casually drop it into conversation today, Celia!

Oh, dear. I was afraid that the paragraph of legal terminology meant what you said it did: “Too late now.” I wonder how many places/states have laws like this one. On TV, they’re always claiming “mistrial” in retrospect. I think.

Just about every place has this kind of rule, Mariann, because it really only addresses these very esoteric technicalities of pleading. What you see on TV are dramatizations of the more usual complaints about actual trial errors.