The “fire-proof court-house”

On the 15th of October 1887, the Governor of Washington Territory reported to the Secretary of the Interior in Washington, D.C., on conditions within that western territory for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1887.1

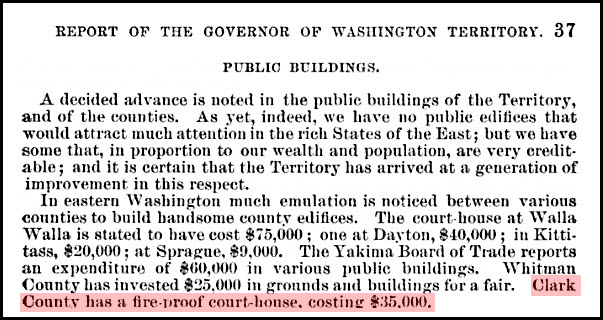

In that report, in the section entitled Public Buildings, he stated2:

So… “Clark County has a fire-proof court-house,” does it?

Not so fast, Mr. Governor.

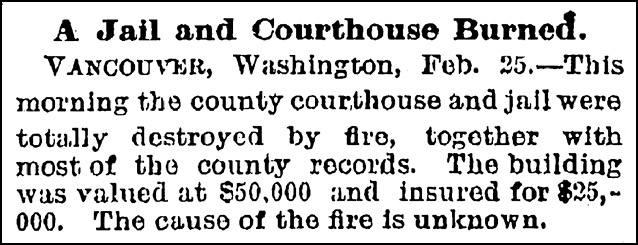

It wasn’t even three years later that newspapers across the country were reporting what the Salt Lake Tribune reported on the 26th of February 18903:

And here’s what Clark County’s own website has to say about that event:

In 1881 the state legislature empowered the county commissioners to float bonds to build a new courthouse and jail. It was completed in 1883 at a cost of $44,000. Seven years later on February 25, 1890, it all went up in smoke.

It was a cold and windy night when fire broke out near midnight in the rear office of County Clerk Elwell’s office and quickly spread to the front of the building and up the tower. Great pieces of burning wood fell off the building, which was consumed in less than an hour. Not even the foundation could be salvaged.

There were ten people asleep in the courthouse and five prisoners in the jail when the fire started. Luckily, all escaped harm. But a great many of the records were burned. Probate records dating back 40 years were destroyed, along with records of the Superior and District courts, Clark County Sheriff, Superintendent of Schools, and Surveyor. The loss of records, especially land claims, would make life difficult for county residents and courts for years to come.4

So if we’re looking for records of court cases before the 24th of February 1890 in Vancouver, Washington, we’re out of luck, aren’t we?

Sure, people will bring in their deeds for re-recording, but all those other legal records — they’re gone forever whenever there’s a fire, right?

Again, not so fast.

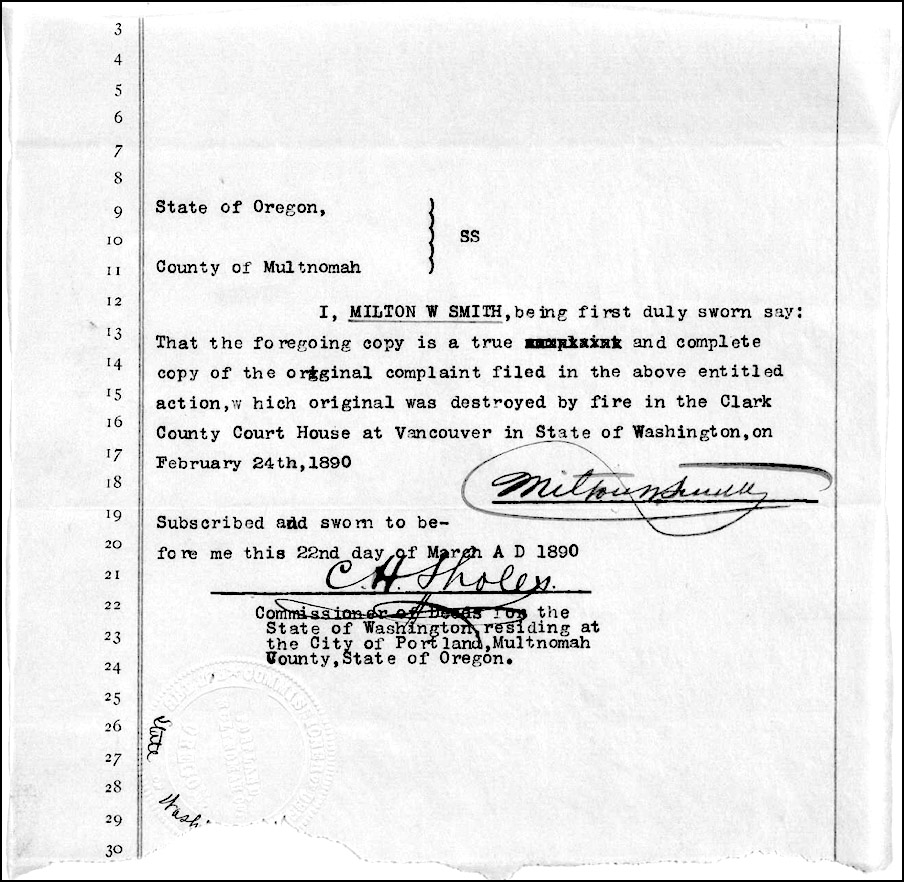

Because sometimes matters that are still pending, unresolved, in a court where the courthouse burned can be reconstructed from records that other people had. Lawyers might have copies of documents filed in the court. Or the litigants might have copies of the papers with which they were served.

Like the complaint in the divorce case of Adams v. Adams, not yet decided at the time of the Clark County Courthouse fire, but re-recorded after the fire with this affidavit5:

So always check. No matter what kind of record we’re looking for, no matter how bad the fire was, no matter what was lost. There still may be a record there waiting to be found.

SOURCES

- Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1887 (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1887); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 28 July 2013). ↩

- Ibid., at 37. ↩

- “A Jail and Courthouse Burned,” Salt Lake Tribune, 26 Feb 1890, p. 1, col. 4; digital images, Newspapers.com (http://www.newspapers.com : accessed 28 July 2013). ↩

- “Second courthouse burns down (1890),” About Clark County, Clark County, Washington (http://www.clark.wa.gov : accessed 28 July 2013). ↩

- Affidavit of Milton W. Smith, 22 March 1890, Clark County Superior Court, Adams v. Adams, Divorce case file no. 11, 1890; County Clerk’s Office, Vancouver, Washington; digital images, “Washington, County Divorce Records, 1852-1950,” FamilySearch< (https://familysearch.org : accessed 15 Jul 2013). ↩

A similar even occurred in New Bern, Craven, NC. I had been conducting some research on the courthouse building in order to recreate a scene of a session of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions. I soon learned that the only known photo of the original courthouse was of the several outer walls left standing after the brick edifice burned down. I imagine that the records (which are still intact) had been re-entered at a later date. Since the early records are all written by hand into volumes by the same penmanship, this leads me to believe that they were re-entries of the original documents.

That’s certainly possible, Debra, but not the only possible explanation. Some records may have been stored offsite (the clerk’s home is the usual place) and some may have been re-recorded when original books were fading. I was doing some research in Lewis County, now West Virginia, and found record books with very early dates — 1820s — that had typewritten contents. Um… no. Turned out the originals were disintegrating and the county decided to preserve the information that way.

I like this bit of optimism. It’s true–don’t assume it’s all lost. When my ancestors’ church burned to ground in Darlington, SC, in 1922, someone still had all the church minutes for the 1800s. I’ve read them on microfilm, in handwriting. Someone must have had them saved at home . . . I’ve never heard that particular story.

Oh now that is really wonderful that those records survived!