Stories told by bonds

You can learn a lot about an area, and about the families that lived there, just by looking at the numbers.

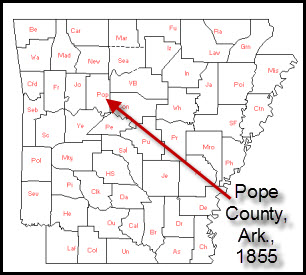

The Pope County, Arkansas, website will tell you the county’s history began when an Indian agency was established there in June 1813, that the first school opened there 1 January 1822, that the county was formed in November 1829, that it’s the 13th largest county in the state by population and 14th by size, with the Arkansas River as its southern border and with the Ozark National Forest on its north side.1

But what was Pope County like, say, in the years just before the Civil War?

But what was Pope County like, say, in the years just before the Civil War?

Where are the stories from, oh, maybe 1855?

For that, we have to look at other numbers.

Numbers like the ones assigned by the Probate Judge of Pope County, Arkansas, in one court session in January 1855.

The numbers of dollars for the surety bonds required to be posted by the guardians of children, usually those who were orphaned:

Jesse Bringle, guardian of Margaret R. Scarlett, 25 January 1855, $400.2

H.A. Howell, guardian of Peacock children (Thomas, Martha and Jesse), 25 January 1855, $3,500.3

Elvira Howell, guardian of Robert and English Howell, 25 January 1855, $10,000.4

David Harkey, guardian of the Shinn children (Martha, B.D.R. Jr., D.M., Sarah and J.L.), 25 January 1855, $1,350.5

William Stout, guardian of the Dare children (Ellen, Jane, Felix, Thomas, James and John), 25 January 1855, $5.6

Henry Howell, guardian of the Hardaway children (Thomas, James and William), 25 January 1855, $1,200.7

Isaac Brown, guardian of Elijah Brown, 25 January 1855, $60.8

John Logan, guardian of Augustus Logan, 26 January 1855, $7,000.9

John Morphis, guardian of the Boyakin children (Charles, Unity, Missouri and Henderson), 25 January 1855, $850.10

So what do numbers like this tell us?

Well, for one thing, they give us an idea of persons who may have died between the 1850 and 1860 censuses in a county that was then fairly lightly populated (4710 people in 1850 and 7883 in 186011, in a state where official death records didn’t start until 1914.12

Take the Peacock family for example. In 1850, A W and Lucy Peacock were living in Johnson County, Arkansas, with five children enumerated on the 1850 census: Lorenzo, age 8; Thomas, age 7; Nancy, age 4; Martha, age 3; and Jesse, age six months.13

Every one of those five children would have required a guardian in January 1855, when H.A. Howell was appointed. Yet only three children were named in the guardianship. So we know that not only did at least one parent die between 1850 and 185514 — but two children did as well.

The numbers also tell us, sometimes, to look for something other than a parent’s death. In the case of the Hardaway children, for example, they were enumerated with their parents James and Martha, in the 1850 census of Pope County15 — and still living with their parents, in Meade County, Kentucky, in 1860.16

So where did the property come from that required the appointment of a guardian? The death of a grandparent, perhaps? And maybe finding the answer to that will explain the move to Kentucky by 1860.

The numbers also give us a general sense of the value of the property the court was trying to protect for the benefit of the children. As of 1855, the law of Arkansas simply required that the security posted be sufficient as determined by the probate court.17 It wasn’t until 1873 that the law required the bond to be in “double the value of the estate.”18

In the numbers set by the court as “sufficient,” we get an idea of the relative economics of these families: the guardian of the Dare children had to post surety in the amount of five dollars, while the guardian of the Howell children — their own mother — had to post surety in the amount of $10,000. The guardian of Elijah Brown posted $60; the guardian of Augustus Logan, $7,000.

And those numbers alone tell us that Pope County wasn’t all the same demographically in 1855 — that it had a very wide gap between its rich and its poor. A fact that may help us place our families in context when we find them in Pope County in that time period.

One moment in time, frozen in the records of the Probate Court.

And stories that can be lost if we don’t think to look for them.

SOURCES

- “Welcome To The Official Pope County, Arkansas Site,” Pope County (http://www.popecountyar.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013). ↩

- Pope County, Arkansas, Guardian & Administrators Bond Record, Book A: 28-29; County Clerk’s Office, Russellville; digital images, “Arkansas, Probate Records, 1817-1979: Pope County,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 1 Aug 2013). ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 30-31. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 32-33. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 34-35. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 36-37. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 38-39. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 40-41. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 42-43. ↩

- Ibid., Book A: 44-45. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Pope County, Arkansas,” rev. 6 Jul 2013. ↩

- “Death Records,” Arkansas Department of Health (http://www.healthy.arkansas.gov/ : accessed 1 Aug 2013). ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Johnson County, Arkansas, population schedule, p. 243 (penned), dwelling/family 66, A W Peacock household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 27. ↩

- An orphan, remember, was a “minor or infant who has lost both (or one) of his or her parents. More particularly, a fatherless child.” See Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 857, “orphan” (emphasis added). ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Pope County, Arkansas, population schedule, p. 281(B) (stamped), dwelling/family 569, James Hardaway household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 29. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Meade County, Kentucky, population schedule, p. 74 (penned), dwelling 512, family 508, James Hardaway household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 386; imaged from FHL microfilm 803386. ↩

- “Guardians and Wards,” Chapter 81, §§10-13, in Josiah Gould, A Digest of the Statutes of Arkansas, Embracing All Laws of a General and Permanent Character in force at the Close of the Session of the General Assembly of 1856… (Little Rock, Arkansas : Johnson & Yerkes, State printers, 1858), 571-572; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013). ↩

- “Guardians, Curators and Wards,” Chapter 76, §3592, in Hill and Sandels, A Digest of the Statutes of Arkansas, Embracing All Laws of a General and Permanent Character in force at the Close of the Session of the General Assembly of 1893… (Columbia, Missouri : E.W. Stephens Press, 1894), 877; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 1 Aug 2013). ↩

Very interesting post, Judy. Thank you!

Thanks for the kind words, Ginny!