The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

In the summer of 1819, a British nobleman found himself irked at the claims of a woman to be his wife. And so he sued, charging in part:

That Lord Hawke is, in no way, married to or united with this lady, that she has falsely and maliciously boasted and reported, that she is married to him, whereas, in fact, no marriage has taken place; and that, on her being desired to desist from such conduct, she paid no attention, but continued, falsely and maliciously, to boast and report such fact, to the no small prejudice and injury of the complainant.1

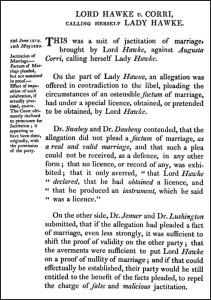

The suit was brought by Lord Hawke, a widower, against Augusta Corri, who annoyed him by calling herself Lady Hawke, in the Consistory Court of London — an ecclesiastical court with jurisdiction over matrimonial and probate matters in England until the mid-1850s.2

The suit was brought by Lord Hawke, a widower, against Augusta Corri, who annoyed him by calling herself Lady Hawke, in the Consistory Court of London — an ecclesiastical court with jurisdiction over matrimonial and probate matters in England until the mid-1850s.2

And it asked the Court to “restrain her from such conduct, and condemn her in the costs of the suit.”3

So… in the lingo of the law, there has to be a cause of action — the “matter for which an action may be brought”; the “ground on which an action maybe sustained”; the “right to bring a suit.”4

What, pray tell, was the cause of action here? What exactly was Lord Hawke suing for?

It was a suit for jactitation.

And, no, actually, The Legal Genealogist had never heard of it before either.

The word jactitation comes the Latin jacitare (“to utter publicly”)5 and, in the law, it means a “false boasting; a false claim; assertions repeated to the prejudice of another’s right.”6

There are several specific types of jactitation:

• “Jactitation of a right to a church sitting appears to be the boasting by a man that he has a right or title to a pew or sitting in a church to which he has legally no title.”7

• “Jactitation of tithes is the boasting by a man that he is entitled to certain tithes to which he has legally no title.”8

• Jactitation of title is a “species of defamation or disparagement of another’s title to real estate known at common law as ‘slander of title’ …, and in some jurisdictions (as in Louisiana) a remedy for this injury is provided under the name of an ‘action of jactitation.’”9

And, of course, the kind Lord Hawke was whining about — jactitation of marriage: “In English ecclesiastical law, the boasting or giving out by a party that he or she is married to some other, whereby a common reputation of their matrimony may ensue. To defeat that result, the person may be put to a proof of the actual marriage, failing which proof, he or she is put to silence about it.”10

It’s actually best described by Sir William Scott, the judge who rendered judgment in the Hawke case on the 16th of May 1820:

This is a proceeding in a cause of jactitation of marriage, brought by Lord Hawke against a female, who, as he represents, had usurped the title and character of his wife — a proceeding not now very familiar to this Court, but which it is bound to receive, for the protection of persons against the extreme inconvenience of unjust claims and pretensions to a marriage, which has no existence whatever. If a person pretends such a marriage, and proclaims it to others, the law considers it as a malicious act, subjecting the party, against whom it is set up, to various disadvantages of fortune and reputation, and imposing upon the public (which, for many reasons, is interested in knowing the real state and condition of the individuals, who compose it) an untrue character; interfering in many possible consequences with the good order of society, as well as the rights of those who are entitled to its protection.11

And, it turned out, that Lord Hawke really wasn’t married to Augusta Corri.

But he still lost the case.

Turns out, you see, that her version was he’d swindled her into believing they were married by taking advantage of her maidenly naivete and having a ceremony performed by a man he told her was a minister of the Church of England. And his version in response to that was that she was no maiden but a woman with a living husband who’d willingly become his mistress and okay, so he’d allowed her to say she was his wife, but only while they were cohabiting.

The Court was Not Amused.

It chose not to get into the he-said-she-said argument over the supposed marriage ceremony and focused on the fact that Lord Hawke himself admitted that he allowed her to say she was his wife and in fact had introduced her as such, even to his children by his late wife:

According to Lord Hawke’s own account, he has been living, for years, in an adulterous connection with the wife of another man, whom, for the conveniences of that connection, he has every where introduced and qualified as his own. What protection he may find in other Courts from the molestation of claims originating from this imposture, which he has practised upon the world, is not for me to inquire. … But this Court cannot indulge him with a general exemption from all possible inconvenience, by pronouncing a sentence of malicious jactitation against the person, whom he himself has tutored to use the language of which he complains. — Suit dismissed.12

Jactitation.

We learned something, you and I, here today.

And, we might imagine, maybe Lord Hawke did too.

SOURCES

- Hawke v. Corri, 2 Hagg. Cons. 280, 281 (1820); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Aug 2013). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Consistory court,” rev. 20 Jul 2013. ↩

- Hawke v. Corri, 2 Hagg. Cons. at 281. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 182, “cause of action.” ↩

- The Free Dictionary (http://www.thefreedictionary.com : accessed 6 Month 2013), “jactitation.” ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 648, “jactitation.” ↩

- Ibid., “jactitation of a right to a church sitting.” ↩

- Ibid., “jactitation of tithes.” ↩

- Ibid., “jactitation.” ↩

- Ibid., “jactitation of marriage.” ↩

- Hawke v. Corri, 2 Hagg. Cons. at 281. ↩

- Ibid., at 291-292. ↩

Is that called the “You can’t have your cake and eat it too” judgement?! ~ ; }

You have it exactly right, Mary Ann! Or the “having made thy bed, lie in it!” judgment.

What a fun post!

Thanks, Donna. I love coming across examples like this!

What was Lord Hawke’s birth name?

The answer is in the court case and Google can provide it as well: Edward Hawke-Harvey, 3rd Baron Hawke (1774–1824) (born Hawke, assumed the additional surname Harvey in his lifetime).