The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

So back on Monday, The Legal Genealogist told the tale of Mary Jane Brewer Holt, the unfortunate lady from Amelia County, Virginia, who had married very young and soon repented herself of that decision.1

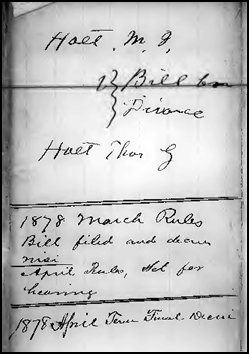

Mary Jane’s 1878 divorce from her husband Thomas G. Holt occupies only 13 images in the chancery causes file digitized at the Library of Virginia’s Virginia Memory project. And one of those is the file folder cover.2

Mary Jane’s 1878 divorce from her husband Thomas G. Holt occupies only 13 images in the chancery causes file digitized at the Library of Virginia’s Virginia Memory project. And one of those is the file folder cover.2

And despite its few pages, the case file is literally chock full of terms and terminology that can send any self-respecting non-lawyer screaming for the exits.

As, for example, in the notation on the back of the complaint that the case involved a decree nisi.

Yeah, that’s Latin, all right. Not the decree part, of course, but the nisi part. So let’s break it down.

Remember that Mary Jane’s case was being heard in a court of equity — the chancery court — because she was looking for something other than just money damages. And a decree is simply “the judgment or sentence of a court of equity.”3

In particular, a decree in equity is “a sentence or order of the court, pronounced on hearing and understanding all the points in issue, and determining the right of all the parties to the suit, according to equity and good conscience.”4

So… what’s this nisi bit?

The word in Latin means “unless,” or “if not.”5 So a decree nisi is a decree that’s going to take effect unless something happens.

As explained in Black’s Law Dictionary, a decree nisi is:

A provisional decree, which will be made absolute on motion unless cause be shown against it. In English practice, it is the order made by the court for divorce, on satisfactory proof being given in support of a petition for dissolution of marriage; it remains imperfect for at least six months, (which period may be shortened by the court down to three,) and then, unless sufficient cause be shown, it is made absolute on motion, and the dissolution takes effect, subject to appeal.6

So in English practice, it was a kind of mandatory cooling-off period — one last chance for the parties to say they actually didn’t want a divorce.

That’s not how it worked in 1878 Virginia. Remember, it’s always a matter of how the law worked not just at a particular time but in a particular place. And in Virginia, the law provided:

If a defendant who appears, fail to plead, answer or demur to the declaration or bill, a rule may be given him to plead. If he fail to appear at the rule day at which the process against him is returned executed, or, when it is returnable to a term, at the first rule day after it is so returned, the plaintiff, if he has filed his declaration or bill, may have a conditional judgment or decree nisi as to such defendant. No service of such decree nisi or conditional judgment shall be necessary. But at the next rule day after the same is entered, if the defendant continue in default, or at the expiration of any rule upon him with which he fails to comply, if the case be in equity, the bill shall be entered as taken for confessed as to him, and if it be at law, judgment shall be entered against him…7

Well, that’s perfectly clear, isn’t it?

No?

Okay, one more time in English.

When somebody files a complaint, the other side is supposed to answer it. When the other side doesn’t answer and doesn’t show up in court, the court usually enters an order telling the other side it has to answer. And a conditional judgment could be entered in favor of the complaining side. Think of it as a warning from the court: “tell your side of this case or I’m ruling against you.” If the other side still doesn’t answer by the time the court said it has to, then the complaining side wins.

Now in Virginia in 1878, you couldn’t get a divorce just because the other side didn’t show up. Remember, there wasn’t any such thing as no-fault divorce back then. Instead, the court had to satisfy itself that the complaining party had good grounds for the divorce.

So what happened in Mary Jane’s case was this:

• In February 1878, Mary Jane filed her divorce complaint in February. Thomas had until the Circuit Court met to hear equity matters in March to answer.

• By the March term, he hadn’t answered.

• At that March term, the court reviewed Mary Jane’s papers, concluded she had made out a case for divorce on the papers and entered the decree nisi in her favor, setting it down for a hearing in April.

• In April, Mary Jane appeared, Thomas didn’t, the court actually heard the evidence, and the decree was made final.

When you run across the term decree nisi in the records you find, remember Mary Jane — and remember: it’s a conditional decree, a court order that will take effect unless something happens to stop it.

SOURCES

- Judy G. Russell, “The Oratrix,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 12 Aug 2013 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 1314 Aug 2013). ↩

- Complaint, Amelia County (Va.) Chancery Causes, 1738-1939, Holt v. Holt, 1878-002; Local Government Records Collection, Amelia County Court Records, The Library of Virginia; digital images, “Chancery Records Index,” Virginia Memory (http://www.virginiamemory.com/collections/chancery/ : accessed 11 Aug 2013). ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 13 Aug 2013), “decree.” ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 341, “decree.” ↩

- The Free Dictionary (http://www.thefreedictionary.com : accessed 13 Aug 2013), “nisi.” ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 341, “decree nisi.” ↩

- “Judgment or decree by confession, or in the office by default,” Chapter 167, §42, in George W. Munford, compiler, Third Edition of the Code of Virginia including Legislation to January 1, 1874 (Richmond : James E. Goode, printer, 1873), 1095; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 13 Aug 2013). ↩