Family fight

Some 65 years ago, a family feud over ownership and control of wooded land in Sumter County, Alabama, broke out in the Circuit Court there.

It seems that Jim Knott had died in 1933, leaving a widow and nine surviving children — three girls and six boys. At the time of his death, he’d owned a three-fourths undivided interest in 290 acres of land in Section 32, Township 16, Range 4 West, a piece of land that was mostly wooded. The other quarter interest was held by a man named John Fitch.

It seems that Jim Knott had died in 1933, leaving a widow and nine surviving children — three girls and six boys. At the time of his death, he’d owned a three-fourths undivided interest in 290 acres of land in Section 32, Township 16, Range 4 West, a piece of land that was mostly wooded. The other quarter interest was held by a man named John Fitch.

After Jim’s death, his son James continued to live on the land and farm it. The deal was, he’d live there rent free as long as he paid the taxes and kept everything on the property in good repair.

But, as things happened, he didn’t keep up with the tax payments, the land was seized and sold for back taxes, James managed to redeem the property from the tax sale — but had the deed put into his name as the sole owner.

James then died in 1944, leaving a widow and three children, two girls and a boy. The younger James’ widow bought out the interest of John Fitch, and then entered into a contract with a Mississippi timber company to sell the timber on the land for $4,500 — with some $900 having been paid over and the other $3600 to be paid.

When the timber company moved a sawmill onto the land, Jim’s widow and other children realized all was not well and hustled into court. By the time the case was decided, one of Jim’s daughters, Sallie, had died, leaving a husband and no children.1

Now The Legal Genealogist is not about to get into the middle of a family fight in terms of who knew what when and whether what was done was innocent or with malice aforethought.

But the final decree entered by the Circuit Court in this case is an absolute doozy — too good not to share. See, the court had to deal with the land and with the cash from the timber sale.

Ready for this?

As to the land, the court said James’ widow owned the one-fourth that she’d bought from John Fitch and, as to the three-fourths that Jim owned at the time of his death:

• Jim’s widow had a dower interest in all of Jim’s land.

• Each of Jim’s children — or their heirs — were entitled to a one-ninth undivided interest in Jim’s land, which meant that

• Sallie’s widower had a life estate in Sallie’s one-ninth which, after his death, would go to her heirs;

• James’ widow had a dower interest in James’ one-ninth which, after her death, would go to her and James’ three children; and

• Each of the seven surviving children had a one-ninth undivided interest.2

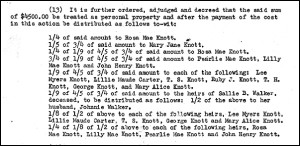

As to the money, the court said it should be divided as follows:

• 1/4 to James’ widow.

• 1/5 of 3/4 to Jim’s widow.

• 1/4 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 to James’ widow.

• 3/4 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 jointly to James’ three children.

• 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 to each of Jim’s seven surviving children.

• 1/2 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 to Jim’s daughter Sally’s widower.

• 1/8 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 to each of Jim’s seven surviving children.

• 1/4 of 1/8 of 1/2 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4 to each of James’ heirs (his widow and three children).3

Egads. It’s enough to make your head hurt.

Now if you work all the math through on the land, it’s actually pretty easy. The court said there were two ownership interests: Jim’s and the interest James’ widow bought. She got all of what she bought, and Jim’s heirs got all of what he owned.

Jim’s widow got her dower interest in Jim’s interest but no outright ownership. Under Alabama law at the time, where there was no will, children received all of the real estate, to the exclusion of the widow; she had dower rights only.4 The nine children, or their heirs, became the owners, subject to the mother’s dower interest. That’s why each child’s share was a one-ninth undivided interest.

It got complicated because two of the children had died. One, Sallie, left a husband but no children — and no will. Her widower didn’t inherit from her; he only got a life estate in her interest, a right called curtesy.5 When he died, that one-ninth would be divided among her heirs — her brothers and sisters. The other, James, left a widow and children. The widow got a dower interest in James’ share, but each of his three children would be the owners of his share. In effect, each got a third of one-ninth, subject to their own mother’s dower rights.

But dower in Alabama at the time was a life estate in one third of the land. So when it came time to divvy up the money, why were the numbers different? Why did Jim’s widow get one-fifth? Why did Sallie’s widower get half of her share?

The answer, as usual, comes from the law. Because the money was personal property and not real estate, a different part of Alabama law applied. And under that different part of the law, the amount a widow was entitled to changed depending on how many children there were. Up to four children, she shared equally with the children, so if one child she and the child each got half, if two children she and each child would take a third and so on. But if there were more than four children, she got one-fifth and the children equally shared the other four-fifths.6

So again, there are two ownership interests, and James’ widow got all of the ownership interest that she’d bought. The complicated numbers are for Jim’s ownership interest. And, there, because of the law, Jim’s widow got one-fifth of his part, and each of his children got one-ninth of the rest.

But then you have the two children who’d already died. James’ heirs got his one-ninth, and under the statute his widow took an equal share with her three children, so each of them got one-fourth of his one-ninth. Sallie’s husband was entitled under the law to only one-half of Sallie’s share,7 with the other half going to her heirs — her brothers and sisters (or their heirs). And since Sallie had eight brothers and sisters, each was entitled to a one-eighth share. The seven surviving brothers and sisters had that added to their share, and James’ widow and three children equally shared his one-eighth.

As always, when you see this kind of “omigosh!” distribution of an estate, you can be sure that there’s a statute — and often more than one! — that needs to be consulted.

And — think about it here — with the statute and the numbers, we can reason backwards to get a pretty good idea of who was who, how the people fit into the family structure. Just as one example, under the statute, only a widow with four or more children would have gotten that one-fifth share of the money.

Neat, huh?

SOURCES

- Sumter County, Alabama, Circuit Court Case File No. 2783, Knott v. Knott, complaint filed 22 April 1948; Circuit Court Clerk’s Office, Livingston Alabama; database and images, “Alabama, Sumter County Circuit Court Files, 1840-1950,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 18 Sep 2013). ↩

- Sumter County, Alabama, Circuit Court Case File No. 2783, Knott v. Knott, decree entered 17 May 1948. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Alabama Code 1923, §§ 7427-7429. ↩

- Alabama Code 1923, § 7376. ↩

- Alabama Code 1923, §7374. ↩

- Alabama Code 1923, § 7376. ↩

OMG my head hurts too!

It’s that last “1/4 of 1/8 of 1/2 of 1/9 of 4/5 of 3/4” that has me reaching for the aspirin…

Judy, I showed this post to Tom and he said, “Yeah, I dealt with some cases pretty much like this.” Makes me glad that I’m not an attorney; it’s like cutting the pie into so many pieces that you can’t see the pieces!

Makes me glad I did criminal law, I’ll tell you!

And how much did the lawyers and accountants get to figure this all out?

I’ve seen some doozies, but this takes the cake

I’ve actually seen worse — one where they were divvying up into something like 1/530ths. Ulp…