Apprenticing freed children

Beverly McGowan Norman has been telling the story of “Augustus Walter Wheat- the One-eyed Merchant of Marthasville, Georgia,” on her blog Roots, Branches, and a Few Nuts.

She’s come across a lot of interesting information, in many different sources, and all of it made Wheat sound like an interesting and upstanding citizen.

She’s come across a lot of interesting information, in many different sources, and all of it made Wheat sound like an interesting and upstanding citizen.

And then she hit the court records. And that’s when the questions came up. “The following I have mixed feelings about…,” she wrote. “Is it a way to get around owning slaves? Are they his former slaves with no other recourse? Did Augustus take them in out of kindness?”

“The following” were two court records in Campbell County, Georgia, the first dated in November 1866 and the second in April 1867. Each one is called an indenture and, in each one, the Court of Ordinary bound children to Wheat as apprentices.

In the first order, dated 6 November 1866, the Ordinary bound to Wheat “minor orphan Children Freedmen having no parents living that are known & having property. Viz. Thompson Wheat boy twelve years old Mary Wheat a girl seven years old Edwin Wheat a boy five years old and Nancy Wheat – a girl three years old.”1

In the second, dated 15 April 1867, the Ordinary bound another boy, named Augustus Wheat, age 15, to the white merchant of the same name, adding “The Said Boy having Chosen and Selected the Said A. W. Wheat for his Master.”2

There actually was a third order that Beverly hadn’t come across, dated 22 June 1867, in which a 16-year-old Robert Edmondson was bound, having chosen Wheat as his master.3

So Beverly really wants to know about these children — the youngest of whom were still living in the Wheat household with Wheat’s widow as of 1880.4 She’d never heard of this apprentice system before, and wondered if it could be some form of adoption.

Clearly, despite the listing on the 1880 census of the two youngest apprenticed children as “son” and “daughter,” they aren’t likely to have been Wheat’s biological children. First, both of the children were enumerated as black, not mulatto, and subsequent records for the male such as the 1900 census and his death certificate consistently show his race as black, not mulatto.5 And Wheat wasn’t listed as the male’s father on that death record either.

Second, if they had been Wheat’s own children, he wouldn’t have needed to have a court order binding them to his as apprentices.

And no, this apprenticeship system wasn’t a benign form of adoption. It was, instead, a time when, all across the south and in border states like Maryland, “children were legally taken away from their families under the guise of ‘providing them with guardianship and “good” homes until they reached the age of consent at twenty-one’ under acts such as the Georgia 1866 Apprentice Act. Such children were generally used as sources of unpaid labor.”6

These particular children may or may not have been Wheat’s own freed slaves — he certainly was a slaveholder, but was shown with only three slaves in 1860, a 45-year-old female and two seven-year-olds, a boy and a girl.7 He could have acquired more by 1866-1867 but these records won’t show that.

The fact that some of them had the surname Wheat is suggestive; almost all of the children bound to white masters around the same time had the same surname as the men to whom they were bound.

What is certain is that, despite the language about choosing a master, they very likely weren’t choosing lives as apprentices.

The fact is, many former slave states immediately after the war passed laws using the structure of apprenticeship to keep freed children under the control of their former white owners as unpaid labor. “Former slaveholders seized upon apprenticeship … as a way to hold onto the children of their freed slaves, often regardless of whether the parents were living or dead.”8

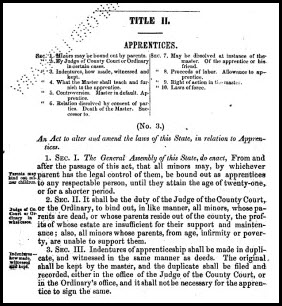

In Georgia, an apprenticeship law was enacted 17 March 1866. Its key provision was that it was “the duty of the Judge of the County Court, or the Ordinary, to bind out, … all minors, whose parents are dead, or whose parents reside out of the county, the profits of whose estate are insufficient for their suppport and maintenance; also all minors whose parents, from age, infirmity or poverty, are unable to support them.”9

Since freed slaves rarely had assets, any freed child in Georgia was subject to being bound out as an apprentice — essentially unpaid labor — to a former owner or other white land owner.

In Campbell County, all of the children bound as apprentices after that statute passed were freed children, such as 11-year-old Fannie Moore, bound to George R. Moore;10 13-year-old Amanda Bullard and five-year-old Ater Bullard to Thomas Bullard;11 15-year-old Charles James and 10-year-old Frank James to John James;12 and seven-year-old Harrison Torrance and five-year-old Fannie Torrance to George Torrance.13

And the reason the children stayed in the Wheat household even after the merchant died was another part of the law that provided that “on the death of the master, the said Judge or the Ordinary, may either dissolve (the apprenticeship), or substitute in the place of the deceased, his legal representative, or some member of his family.”14 The way the law worked is the apprentice stayed where he or she was unless the court ordered a change.

Under the terms of the indenture, Wheat was to “teach the said apprentices the businesses of house service husbandry and farming shall furnish them with sufficient wholesome food suitable clothing and necessary medicine and medical attention shall teach them habits of industry honesty & morality & shall cause them to be taught to read English.”15

Whether Wheat and his family kept their side of the bargain isn’t entirely clear. The youngest apprentices still with the Wheats were shown as age 18 and 15 respectively — and as unable to read or write — on the 1880 census.16

The children had no choice but to keep their side. The law required it.

SOURCES

- Campbell County, Georgia, Estate Bond Book B: 247, indenture dated 6 Nov 1866; digital images, “Georgia, Probate Records, 1742-1975,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 6 Oct 2013). ↩

- Ibid., Estate Bond Book B: 256-257, indenture dated 15 April 1867. ↩

- Ibid., Estate Bond Book B: 265, indenture dated 22 June 1867. ↩

- 1880 U.S. census, Douglas County, Georgia, District 1273, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 50, p. 185(A) (stamped), dwelling 127, family 127, Edward and Nancy Wheate in Mary Wheate household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 6 Oct 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication T9, roll 144; imaged from FHL microfilm 1254144. ↩

- See 1900 U.S. census, Douglas County, Georgia, Salt Springs, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 24, p. 36(A) (stamped), dwelling 237, family 237, Edgar Wheat; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 6 Oct 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication T623, roll 194; imaged from FHL microfilm 1240194. And see George State death certificate no. 20048-C, Ed Wheat, 7 Aug 1921; digital images, “Georgia, Deaths, 1914-1927,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 6 Oct 2013). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Reconstruction Era,” rev. 4 Oct 2013, citing Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 21–73. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Campbell County, Georgia, slave schedule, p. 320(B) (stamped), line 27 (right hand column), Augustus W. Wheat, owner; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 6 Oct 2013); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 143. ↩

- Mary Niall Mitchell, “‘Free Ourselves, but Deprived of Our Children’ : Freedchildren and Their Labor after the Civil War,” in James Alan Marten, ed., Children and Youth During the Civil War Era (New York : NYU Press, 2012), 163. ↩

- § II, Act of 17 March 1866, in Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, … 1865-1866 (Milledgeville, Ga. : State Printer), 6-8; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 6 Oct 2013). ↩

- Campbell County, Georgia, Estate Bond Book B: 254, indenture dated 7 Jan 1867; digital images, “Georgia, Probate Records, 1742-1975,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 6 Oct 2013). ↩

- Ibid., Bond Book B: 255, indenture dated 27 Feb 1867. ↩

- Ibid., Bond Book B: 282, indenture dated 23 Jan 1868. ↩

- Ibid., Bond Book B: 286, indenture dated 12 Feb 1868. ↩

- § VI, Act of 17 March 1866, in Acts of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, … 1865-1866. ↩

- See e.g. Campbell County, Georgia, Estate Bond Book B: 247, indenture dated 6 Nov 1866. ↩

- 1880 U.S. census, Douglas Co., Ga., Dist. 1273, pop. sched., ED 50, p. 185(A) (stamped), dwell./fam. 127, Edward and Nancy Wheate in Mary Wheate household. ↩

Exceedingly apt topic and one that should be used by all participating in the Gilder Lehrman and NEH series “Created Equal: America’s Civil Rights Struggle.” This will fit under “Slavery by Another Name” and should be read by all historians and genealogists.

Thanks for the kind words, Nan.

Thank you so much for answering my questions and helping me understand this apprenticeship system…never saw this in our history books!

Glad I could help, Beverly. (There’s a lot that’s not in the history books…)

A line of this post which really caught my eye is in the 5th paragraph: . . .”minor orphan Children Freedmen having no parents living that are known & having property.” If they had property, what happened to the property? Would it go to the person to whom they were apprenticed; was it turned over to them at the end of the indenture (which didn’t seem to take place for these children); was it sold and the money “used for the care of the children>!?!?!? Am I misreading this or does it actually say that they “had property”??

It’s the usual awkward phrasing problem, Mary Ann. It means that the children had no parents who were known to be living who had property that would enable them to take care of the children. Children who had no parents (or actually no living father) but who had property that would have supported their needs would have had a guardian appointed, rather than being apprenticed to someone.

What many forget is that the apprenticeship system was around for a long, long time before the 1866 law. Earlier apprenticeship laws were designed (in theory, although not always in practice) to keep the poor, regardless of color or ethnicity, from being a financial burden to the county where they lived.

Were there abuses? Absolutely! But not always. Even after the 1866 law, some parents *chose* to find “masters” for their children out of necessity. One example I came across in the past few years was in the family of Priscilla Walker, who apparently lived in a state of abject poverty (1880 US census). In 1877, she voluntarily bound her eldest son out to Peter G. Walker. By 1880, she had bound another daughter out, although to whom is unknown. This is likely all that kept those children from starving.

As genealogists, we have the privilege of being able to delve into the personal lives of our ancestors to see how laws and culture affected the individual and the family. Historians often sweep families like Priscilla’s under the rug as anomalous, but these anomalies happened more often than most people realize, and we should bear that in mind as we research.

The binding out of orphaned children was of long-standing, and it was the community’s way of keeping those children from being a drain on the community and of keeping them in the community to contribute to it as they reached adulthood. It was the functional equivalent of today’s foster care. What distinguishes the post-Civil War apprentice laws is that they were specifically geared to freed children, could be invoked whether the parents were living or not, often were skewed so that the parents couldn’t keep their own children (in some states, for example, all illegitimate children were subject to being bound out and children born as slaves were all considered illegitimate even if the parents then married) and greatly favored the former slaveowner (who even had statutory preference in some states). There were cases in Maryland where the freed children of US Colored Troops were being bound out.

I have seen many apprenticeship records in early (after ca. 1685)Pennsylvania, one involving my immigrant ancestor’s son. A young boy was apprenticed (the term used in the court document)to James Hendricks for a specific period of time. In this case I believe it was “until the youth reaches the age of 21.” The document doesn’t specify that the boy was orphaned.

This is great information! I have also read that in the case of a child being orphaned, they may be apprenticed even if they had family who wanted to take them in. I read in “To Joy My Freedom” a situation where one child was kidnapped from their “master” by an Aunt who had tried unsuccessfully to gain custody. Do you know how long this practice went on for? Into the early 1900s?

Amber, the forced apprenticeships were — of necessity — time limited. When those who were children at the time of emancipation reached legal age — so likely a maximum of 21 years from 1865 — no court could hold a child as bound out to the former master. That doesn’t mean the practice of binding children out ended then, but the slavery link wasn’t nearly as prevalent more than a few years after the Civil War. Binding children out continued for varying periods depending on the state.

I actually have a case in Campbell County, Georgia in 1875 where a 5 year old child was bound as an apprentice to her grandmother. The child’s mother died 3 years prior and the grandmother indicated in the court record that the mother had requested that she, the grandmother “should raise and train her daughter.” The child’s father was still living in a nearby county along with his son two years older(by the same mother) and his new wife. I don’t understand why the child would be apprenticed to the grandmother rather than the her grandmother becoming her guardian. I knew the grandmother had raised the little girl but I always thought it had been done as a kindness. Finding this record of her being apprenticed to her grandmother seems to paint a little different picture.

Remember that a guardianship in that time frame was only for property. To assign legal responsibility for the child, the binding out was needed. So it still could be a kindness by the grandmother to take her, and the legal responsibility for her.