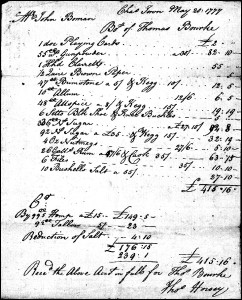

The receipt

It’s just a single piece of paper, one of 15 or so tucked into a folder of court records, then put into a box with more court records, at the North Carolina State Archives.

But oh… what questions it makes us answer!

• What’s a quire?

• What would you do with brimstone?

• How about alum?

• How much of anything would fit in a hogshead?

• And what spice would have set you back a pretty penny in the year 1777?

In May of 1777, John Bowman, a storekeeper from Burke County, North Carolina, paid more than £415 for supplies he purchased in Charleston, South Carolina. He got a receipt for what he’d paid, and it ended up in loose court papers from Burke County, now in the North Carolina State Archives.1 You can see the receipt here — click on the image to see it enlarged.

Some of the items are just plain fun. He bought a dozen sets of playing cards for £2, for example, and 26 gallons of rum for more than £63. Some are interesting: he bought a lot of gunpowder and a variety of spices including what looks like two different kinds — or two different qualities — of sugar.

And then there are those questions… questions that sent The Legal Genealogist scurrying for reference books.

He bought “1 Hhd Clarrette.” A hogshead of some red wine, that was, might have been French wine but could just have been any red wine.2

Okay, so… um… what’s a hogshead? And though, I confess, I was seeing that scene from The Godfather with the horse’s head in my mind’s eye, it has nothing to do with heads, or hogs either, for that matter. It was, instead, “a measure of a capacity containing the fourth part of a tun, or sixty three gallons.”3

And he bought a half quire of brown paper for five shillings. Quire: “A set of 24 or sometimes 25 sheets of paper of the same size and stock; one twentieth of a ream.”4 Clearly, brown paper wasn’t a hot seller in the backcountry of 1777 North Carolina.

And he bought brimstone. Brimstone! As in “fire and brimstone!” What in the world? Turns out brimstone was sulfur, and it had a number of uses. It was one of the components of black gunpowder, it was used in medicines including creams for scabies, ringworm, psoriasis, eczema, and acne, and furniture makers used it for inlays.5

And he bought alum — which might have been used for fixing dyes in wool or in purifying water, but considering the backcountry, was most likely used in the process of “tanning of animal hides to remove moisture, prevent rotting, and produce a type of leather.”6

And look at the price he paid for nutmeg! Four ounces of nutmeg set Bowman back more than £5. Why? Because the Dutch had an effective monopoly on the spice and kept the price high. “In 1760, the price of nutmeg in London was 85 to 90 shillings per pound, a price kept artificially high by the Dutch voluntarily burning full warehouses of nutmegs in Amsterdam.”7 And clearly even more on this side of the Atlantic.

History, economics, medicine… all in one document… all in a genealogist’s day’s work.

SOURCES

- Receipt, Thomas Bourke to John Bowman, 20 May 1777, Burke County, North Carolina, Civil action papers 1755-1783, folder 1777, North Carolina State Archives C.R.014.325.1; digital images, “North Carolina, Civil Action Court Papers, 1712-1970,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 7 Oct 2013). ↩

- The Free Dictionary (http://www.thefreedictionary.com : accessed 7 Oct 2013), “claret.” ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 575, “hogshead.” ↩

- The Free Dictionary (http://www.thefreedictionary.com : accessed 7 Oct 2013), “quire.” ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Sulfur,” rev. 4 Oct 2013. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “Alum,” rev. 2 Oct 2013. ↩

- Peggy Trowbridge Filippone, “Nutmeg and Mace History,” About.com Home Cooking (http://homecooking.about.com : accessed 7 Oct 2013). ↩

This article made me remember my first graduate English professor vividly. We had to learn about papers used in the early days of printing, and how to fold them correctly to produce a folio, quarto etc. Dr. Meserole was such a fountain of information and all of his lectures and assignments ensured that we not only knew the materials but also knew the history surrounding their creation and use. I have always asked “Why” and “How” but he taught me how to pursue my questions until I answered them, and the reasons behind the answers. Thanks!

I would have loved that professor, Nan (and yeah, figuring out how to fold a quire is fun!).

12 decks of cards and 26 gallons of rum?! That’s one heck of a poker game!

Don’t forget that hogshead of wine!

The wine mentioned here was probably “Claret” which, according to my OED was originally from the Bordeaux region of France (weren’t all wines originally from there?) It is a red wine, except that again my OED says it was sometimes “yellowish” which probably means that the wine was made without leaving the skins on for a period of time—which is what creates the color. My OED definition of hogshead also mentions specifically a “63 gallon wine cask” but apparently many different amounts were assigned the description “hogshead” over the years. I’m not correcting, just clarifying.

Claret is indeed a Bordeaux wine… except maybe not in colonial and early America, when the word is just as likely to have been used as a generic term for a red wine. I envy you your OED — something I keep thinking I need and never get around to actually buying.

Oops! It’s not an OED! It’s at least 30 years old and I keep it around because it is so useful and I’m afraid if I update it, I will wind up with one that has dropped a lot of the old words I’m usually interested in, and that the offerings of archaic uses, great definitions, and lists of synonyms will be missing. For instance, the word “hold” takes up almost an entire column—and it is a large dictionary. I had a special stand built for it and it sits open on my buffet, ready for use. It is a Webster’s Unabridged. When I got it, my kids were in school and were always needing to know about words that were not thoroughly covered in the school dictionaries they used. I went to the local book store intending to get an OED, but they didn’t have any on hand. I liked this dictionary so bought it, thinking that I would upgrade after a few years. But it was so useful that I never replaced it. Since it’s always open and I rarely see the cover, I guess my mind just turned it into the OED which I had expected to buy!!

Now we’re BOTH going to have to go buy an OED!

Absolutely loved this, Judy! Have always loved these old documents and the questions they brought to mind. I’m glad this receipt had so many items of curiosity. A fun and informative post. Glad you did the research on those unusual words for us and was curious enough to find out why, for instance, they charged so much for that nutmeg!! Thanks!

What a fun glimpse into the past! Brimstone/sulphur is also (still) used in drying fruit and alum in making pickles. Food preservation was an essential activity in those days! (And I second the Bordeaux-claret note. Bordeaux was a huge exporter of wine in the 18th century. Maybe clarrette was any old red wine; maybe it was a nice cabernet. How many wines were produced in the U.S. then?)

I suspect not nearly enough produced for the demand!! (Which still seems to be true today, come to think of it…)

Oh my, Judy. You are primed for a trip to California!! Come on out and I’ll take you to the Napa and Sonoma Valleys (and they are far from the only wine producers, but they’re closest to me) and you will see so many wineries that you’ll realize you probably couldn’t visit them all in your lifetime if you visited one a day! Wines (may not be the best, but wine nevertheless) are prevalent in a variety of stores, sometimes several aisles full of them. I used to at least try to keep some kind of track of the Napa Valley wine industry because that’s where we have our small vineyard, but it’s now too overwhelming to do even that!

One of these days… oh, definitely, one of these days…

Alum is used in pickling too. I still use it for my 28 day sweet pickles done in a large crock.

Thanks to you and the other picklers for the info!

I realize I’m late to the party, but when you mentioned hogsheads I couldn’t resist. Since you have ancestors who followed a similar migration path to some of mine (Virginia & North Carolina to other states in the “Old Southwest” like Georgia & Alabama), I thought you might be interested in two other uses for hogsheads. A hogshead (abbreviatied hhd.) referred to a common unit of measure for tobacco as well as the barrel that was the means of storage for that tobacco. (There’s an illustration and more information at the NCpedia: http://ncpedia.org/tobacco/barrels.) Because tobacco was used as currency in Colonial Virginia, you might also see a hogshead of tobacco referred to in financial transactions where other goods or services were valued in relation to the tobacco “currency.” Growers even used tobacco to pay their taxes.

But I think the hogshead barrel used as a means of transporting goods is even more interesting. In the early days, migrating families who were unable to afford a wagon would use a hogshead barrel to haul their household goods. Sometimes, regardless of the state of their finances, the travelers were forced to follow old narrow trails filled with ruts where a wagon simply would not have been an option. Any barrel sturdy enough to hold 1000 pounds of tobacco would almost certainly stand up to the rigors of wilderness travel better than a wagon.

So how did it work to carry goods in a hogshead? They placed the barrel on its side and inserted an axle through the center (end to end, parallel to the ground) so it would roll when pulled behind a pair of donkeys or oxen. It’s hard to describe, but easy to understand if you have a picture. Here’s an illustration from the Digital Library of Georgia: http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/gastudiesimages/Hogshead.htm.

That is absolutely wonderful, Kathy — and you’re right: the picture is worth 1000 words here. Thanks!

The receipt was a wonderful find. Along with estate inventories and the merchants’ accounts presented for payments by estate administrators, such stories of goods and their prices present invaluable glimpses into the material culture of our relatives and ancestors. In one such merchant’s account, the husband of one of my distant cousins purchased an average of a 1/2-pint of whiskey per day — duly recorded as nearly daily events by the vendor! Then there is the single account entry in another cousin’s 1836 estate record — a bill for a pair of shoes purchased on Christmas Eve. My cousin, regrettably, died 2 days later, and I’ve long wondered who the shoes were for.

Accounts ledgers, kept by farmers, artisans and merchants alike, are also very valuable pictures of the material wants and habits of family/neighbors. One meticulous German handweaver known to me entered every item he gave to each child, together with his valuation of each — which was a record he referred to in his will when designating what further goods were to be allowed each one.

Such records make families’ lives virtually jump off the page.

>> Such records make families’ lives virtually jump off the page.

Worth repeating, because so true!

I will gladly trade 5 quire of paper tomorrow for a Hogshead of wine today..

As always good stuff Judy and I learned something new today 🙂

Thanks for the kind words!

Any idea of what the prices for these goods would convert to in modern American currency?

You might try some of the calculators at eh.net: https://eh.net/howmuchisthat/