Ignoring the exception

It was the spring of 1783. And America was, at long last, at peace.

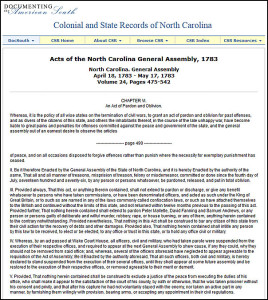

And, the Legislature of North Carolina declared:

it is the policy of all wise states on the termination of civil wars, to grant an act of pardon and oblivion for past offenses, and as divers of the citizens of this state, and others the inhabitants thereof, in the course of the late unhappy war, have become liable to great pains and penalties for offenses committed against the peace and government of the state, and the general assembly out of an earnest desire to observe the articles of peace, and on all occasions disposed to forgive offences rather than punish where the necessity for exemplary punishment has ceased.1

An Act of Pardon and Oblivion.

Pardon, okay. The Legal Genealogist gets that. It’s an “act of grace, proceeding from the power intrusted with the execution of the laws, which exempts the individual on whom it is bestowed from the punishment the law inflicts for a crime he has committed.”2

But “oblivion”?

You won’t find that by looking up that word in any of the old American law dictionaries. Not in Black’s.3 Not in Bouvier’s.4

But you will find it in the dictionaries — as part of the definition of the term amnesty.

Black defines that as a “sovereign act of pardon and oblivion for past acts, granted by a government to all persons (or to certain persons) who have been guilty of crime or delict, generally political offenses,—treason, sedition, rebellion,—and often conditioned upon their return to obedience and duty within a prescribed time.”5 And Bouvier says it’s an “act of oblivion of past offences, granted by the government to those who have been guilty of any neglect or crime, usually upon condition that they return to their duty within a certain period.”6

And so, in the statute, the fledgling State of North Carolina provided that “all and all manner of treasons, misprision of treason, felony or misdemeanor, committed or done since the fourth day of July, seventeen hundred and seventy-six, by any person or persons whatsoever, be pardoned, released, and put in total oblivion.”7

But not for everybody.

No, there was no amnesty for those who’d engaged in deliberate and wilful murder, robbery, rape, or house burning.8

And there were three people — and only three — who were specifically named in the act as never being entitled to the benefit of the law. Three Loyalists whose loyalty to the British crown was too much for North Carolina to forgive.

David Fanning had had the audacity to capture the Patriot Governor of North Carolina, Thomas Burke, and other Patriot leaders, and deliver them to the British Army.9 No pardon and oblivion for him.

Samuel Andrews had been captured by patriot troops and released after taking the oath of loyalty. He went back on his word, raised a militia company to back Cornwallis’ forces and served with Fanning.10

But Peter Mallett (spelled Mallette in the act) is the one who intrigues me. There isn’t any clear information I could find as to just what he’d done that so annoyed the North Carolina Legislature.

One source says he was wrongly suspectedly of disloyalty and his name was removed from the act.11

Um… not exactly. The legislative and judicial records tell another story — a story of a loyalist who outfoxed the Legislature.

Mallett had left North Carolina towards the end of the war but came back under a flag of truce in January 1782. Governor Burke warned him that, if he stayed, he would “be escorted to Mr. Justice Ashe, who will proceed agreeably to the Laws of the Land.”12

Mallett stayed, and in May 1782, the Legislature directed the Attorney General to prosecute Mallett for treason.13

Mallett was tried at Wilmington in June 1783 — and he took advantage of the fact that many other cases were tried that same court term where the defendants got off because of the new act.14 (That’s the big genealogical significance here — there may be tons of records of these cases in the months and even years after the end of the Revolution.)

In Mallett’s case, even though the act had been passed, even though the court knew about it, and even though he was specifically excluded from the benefit of the act — he asked the court to apply it to him anyway.15

Sounds an awful lot like killing your parents and throwing yourself on the mercy of the court as an orphan, doesn’t it?

But it worked for Peter Mallett. The jury bought it — it found him not guilty because of the act.16

Mallett had to go back to the Legislature again in 1786-1787 when the courts refused to let him sue for debt on the grounds that his name was still in that bill. He won there again because of the jury verdict.17

Pardon and oblivion. Even for one who got it when he shouldn’t have.

SOURCES

- Laws of North Carolina, 1783, chapter VI, An Act of Pardon and Oblivion, in Walter Clark, compiler, State Records of North Carolina, Vol. 24 (Goldsboro, N.C. : Book & Job, 1905), 489-490; online version, “Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,” Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/ : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 868, “pardon.” ↩

- Entries jump from “obliteration” to “obloquy.” Ibid., 841. ↩

- Entries there jump from “obligor” to “obreption.” John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 68, “amnesty.” ↩

- Bouvier, A Law Dictionary…, “amnesty.” ↩

- Laws of North Carolina, 1783, chapter VI, §II. ↩

- Ibid., §III. ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “David Fanning (loyalist),” rev. 19 Jun 2013. ↩

- Carole Watterson Troxler, “Andrews, Samuel,” NCPedia (http://ncpedia.org : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

- William Powell, North Carolina: A History (Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 1988), Kindle edition. ↩

- Burke to Mallett, 5 Feb 1782, in Clark, comp., State Records of North Carolina, Vol. 16, 188; online version, “Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,” Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/ : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

- Ibid., at 186, Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, 17 May 1782. ↩

- Jeffery P. Lucas, Cooling by Degrees: Reintegration of Loyalists in North Carolina, 1776-1790; Master’s Thesis, History, North Carolina State University (May, 2007); PDF file (http://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/ir/bitstream/1840.16/2724/1/etd.pdf : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, 1 January 1787, in Clark, comp., State Records of North Carolina, Vol. 18, 421-422; online version, “Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,” Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/ : accessed 3 Nov 2013). ↩

Certainly there were many who weren’t “excused” under this law. My ggg grandfather, Amos Hendrix, had his North Carolina land taken away, and he and many of his in-laws and, perhaps, siblings moved to South Carolina. At the moment I don’t have access to my on-line genealogy info, so can’t refresh my mind on the particulars. This post gives me some resources to follow up on. Thanks.

Land confiscations weren’t affected by this law, Mary Ann. Loyalists often lost land much earlier than this statute — and nothing in the law was intended to give it back. This really was a matter of putting an end to the treason trials.

The term oblivion, indeed the title of the Act, very likely derives from a similarly-named Act passed by the English (as it then was) Parliament in 1651: certain of the text and clauses bear close comparison. Possibly there was a copy of the 1651 Act in a compiled volume of Acts available to the North Carolina legislature in 1783. Certainly, the English Civil Wars of the 1640s were likely to have been the most likely prior example in their minds. The members of the legislature together with their legal advisors had been British until only a few years earlier, and their legal system closely modelled on the British system.

See http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=56460 for full text of the 1651 Act.

No doubt they modeled it on their British forebears… The common law’s arm stretched very long into America.