Access to land

When reader Jeanne Sawtelle saw the definition of the word landlocked here at The Legal Genealogist back on October 23rd,1 her jaw dropped.

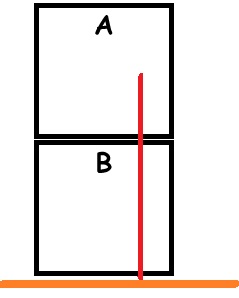

That’s a term, you may recall, that describes the piece of land you see in the image here — it’s an “expression sometimes applied to a piece of land belonging to one person and surrounded by land belonging to other persons, so that it cannot be approached except over their land.”2

That’s a term, you may recall, that describes the piece of land you see in the image here — it’s an “expression sometimes applied to a piece of land belonging to one person and surrounded by land belonging to other persons, so that it cannot be approached except over their land.”2

“Is there a way someone can get to their land?” she asked. “Or are they out of luck? I can’t imagine anyone buying such a piece of land.”

There is a way, and you’ll see it in the deed books all the time, so it’s a concept a genealogist needs to understand.

It’s called an easement.

The term itself is defined as a “right in the owner of one parcel of land, by reason of such ownership, to use the land of another for a special purpose not inconsistent with a general property in the owner.”3

So an easement always affects at least two pieces of land: the owner of the land that’s benefited by the easement (the so-called “dominant tenement”4) and the owner of the land that’s being used by the other owner (the so-called “servient tenement”).

So an easement always affects at least two pieces of land: the owner of the land that’s benefited by the easement (the so-called “dominant tenement”4) and the owner of the land that’s being used by the other owner (the so-called “servient tenement”).

Looking at the image here on the right, you see the simplest example of an easement. A owns one piece of land and B owns the other. The public road is at the bottom, running along B’s southern boundary line. So how is A supposed to get to A’s property?

A needs the right to use the line shown in red — that driveway (or wagon road or even footpath) — to cross over B’s land to get to his own, and that right to cross B’s land is what’s called an easement.

And easements come in lots of flavors:

• An affirmative easement is one where the owner of the servient land has to allow the owner of the dominant land to do something, like pass over the land to get to his own land.

• A negatve easement is one where the owner of the servient land is barred from doing something on his own land that would affect the dominant land, like build a building that would block the dominant land owner’s view of the ocean.

• An easement of necessity is one that’s absolutely essential for the owner of the dominant land to be able to enjoy that land.

• An easement of convenience is one that makes it easier for the owner of the dominant land to enjoy it or use it in a particular way, without being absolutely necessary for that purpose.

• A private easement is one that benefits only the owner of the dominant land, like the right to use a driveway to get through to his own property.

• A public easement is one that benefits the members of an entire community, like the right to use a footpath to get through private land to get to a public beach.

Putting all those together, our landowner A above has an affirmative private easement of necessity.

And, other than helping understand the terms that may be in the deeds we use, why do we as genealogists care about easements?

Because they may very well tell us something about our families.

Think about it for a minute. You’re B. You’re out there in the middle of nowhere in a brand new land. Just who is it who’s likely to end up as A, the person to whom you’re willing to give access across your land?

Family, that’s who. Not always, of course. There are lots of reasons why you might be willing to give someone else access (lots of money paid for an easement being a very good reason, for example). And as the country got more and more settled and lands got divided into smaller and smaller pieces, the odds that a buyer or subsequent owner is going to be family would certainly go down.

But whenever you see an easement recorded in a deed for the very first time, or a deed in which a seller reserves for himself an easement (that would be if A sold or gave the land to B and needed the easement for his own benefit), at least consider the possibility of a relationship between A and B.

It’s — dare I use the pun? — an easy clue to look for…

SOURCES

Easement image: Adapted from Ontheinternets at en.wikipedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Judy G. Russell, “Term of the day: landlocked,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 23 Oct 2013 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 4 Nov 2013). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 688, “landlocked.” ↩

- Ibid., 405, “easement.” ↩

- In this context, tenement just means land, not the kind of run-down cinder-block tenement we think of in a city environment. See ibid., 1160, “tenement.” ↩

Thanks, Judy.

An “easement” is what we would call a “servitude” in Romanic or Roman-Dutch legal systems or in civil law-based systems — whereas in the US “servitude” has all to do with slavery and indentured labour and matters relating to the economic value or utilisation of the human person.

Regards

Dave

You’re absolutely right, Dave: “servitude” would be the closest equivalent in a civil law system.

Judy – I’m having some awful bar review flashbacks here! 🙂

The suggestion to at least consider a relationship based on the existence of an easement is brilliant, by the way. It makes perfect logical sense.

At least I haven’t written about the rule against perpetuities, Blaine… yet. 🙂

Thanks for the kind words!

This is fascinating commentary. Now my question is, when descendants’ access to a family cemetery is stipulated by the granting parties in a deed, even where the specific route is not spelled out, is that also an easement or is it something else? Is the easement the road/path/driveway or is it the access by means that may not be spelled out? Would the same hold true for the privilege of a seat in a church pew that was otherwise held by a specific family?

Fascinating. I’ve been researching a very long-running case in the Court of Chancery in London which dealt with land which, while not landlocked on the surface, was effectively landlocked underground.

The plaintiffs bought a farm in Wales. Not explicit in the case file, but implicit, is that they hoped tomake money from the coal and iron ore which lay under that land. For some years they did nothing much to exploit the land, although they did try to sell at one point (and were frustrated by a quirk of copyhold land ownership).

Then it came to their attention that the defendants were mining coal under their farm. There are a series of ups and downs in the court records.

Later it transpired that the defendants were not only mining coal under the plaintiffs’ farm, they were also carrying coal mined on their own property under the plaintiffs’ farm.

The action started in 1866 and took nearly 20 years to complete in court, not helped by someone else in a separate case claiming she owned the mineral rights to the land (she lost), and also not helped by the death of some of the defendants and some of the plaintiffs – as well as the death of all but one of the lawyers who began the case. The deaths of the defendants led to further litigation on the issue of aetio personalis moritur cum persona, that is as I understand it that “where a wrong has been done by a man to another, giving that other a right to damages, the right is gone if the wrongdoer dies before final judgement is obtained against him, unless it can be shown that estate has profited by the wrong.” Absolutely fascinating.

In the end

Sounds like a great case, Graham — lots of ins and outs! Those mineral rights cases can be really tricky, too.