Mixing it up with autosomal DNA

Remember when you were a kid and you did something your mother didn’t like?

Remember what she’d say?

Remember what she’d say?

“Why can’t you be more like (fill in the blank with the name of the particular sibling, cousin or neighbor who was the role model of the day)?”

Boy did The Legal Genealogist hate that. But boy do I understand it with DNA testing. Because I find myself thinking over and over… why can’t autosomal DNA be more like, say, YDNA?

Working with YDNA results is often a joy.

YDNA, remember, is the kind of DNA that only men have, since only men have a Y chromosome, and it changes very little as it’s passed from father to son to son down the generations.1

So when you’re testing a theory with YDNA, the results are often pretty clear-cut. Test two men you think should be related along a direct paternal line, both have — say — identical values in 36 of 37 markers, and voila! You have your answer. It’s a “close genealogical match … within the range of most well-established surname lineages in Western Europe.”2

Not so with autosomal DNA — the kind of DNA inherited from both parents by way of our autosomal chromosomes.3 An autosomal DNA test works across genders and helps us find cousins with whom we share DNA from all parts of our family tree, paternal and maternal alike.4

Unlike YDNA, autosomal DNA changes — a lot! — with each and every generation because of a process called recombination. That’s a process where all of the pieces of autosomal DNA we inherited from our parents — what’s in each pair of chromosomes we have — gets mixed and jumbled before half (and only half) of those pieces gets passed on to the next generation.5

That process happens with each child separately, so even full blood siblings — brothers and sisters — won’t get exactly the same pieces from their parents. And since Mom and Dad resulted from the same sort of random mixing of their parents’ DNA, the brothers and sisters each inherited different bits and pieces from their grandparents.6

That’s why we say that siblings share 50% of their DNA, and that they share 50% of their parents’ DNA — but it won’t be the same 50% from sibling to sibling.

Reading that, it’s hard to imagine, isn’t it? Words just don’t paint a clear enough picture.

So let’s look at the picture instead.

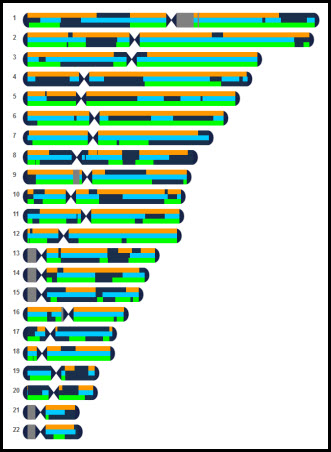

This week, a fourth set of results came in for one more of my late mother’s brothers and sisters. These results are from her youngest sister, so we now have results for four full blood siblings — two of my uncles, two of my aunts.

Line them up in what’s called the chromosome browser, the way they appear in the graphic above, and you can see that there are areas where they just don’t match. Here’s a close-up example:

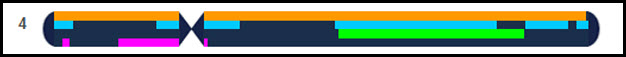

The image above shows a comparison of the autosomal DNA of all four on chromosome 4 — one of 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes all humans have. The dark background is my Uncle David, so the other three are being compared to him.

• In orange is the older of the two sisters, my Aunt Carol. You can see that Carol matches David just about the entire length of chromosome 4.

• In light blue is my Uncle Mike. Mike matches David in only some of the areas where Carol does. There are big chunks of chromosome 4 that David and Carol got that Mike didn’t.

• And in green is the baby, my Aunt Trisha. Trisha matches David only in that one big segment on the right. There are whole areas of her DNA on that chromosome that are different from her oldest brother’s DNA.

We can even put a name on some of that DNA on the left that David and Carol and Mike got, and Trisha didn’t. Look at this image:

Added to the mix in pink is a first cousin to these siblings. Michael is a cousin on my grandmother’s, Robertson, side. David and Carol both got all the same Robertson genes that Michael got. Mike has some of them. Trisha didn’t get any of those particular genes on that particular chromosome. That may be an area where she got a bigger batch from her mother’s mother, rather than her mother’s father, when the random mixing put together what she’d get on chromosome 4.

So what difference does this make? Think about it: say Trisha was the only one we could test and chromosome 4 was the only area we could look at. Would we be able to say we had a match? No. But by adding in the others, the match is clear.

So the lesson, again, is… test everybody you can afford to test.

Which reminds me… I haven’t sent Uncle Jerry his kit yet…

SOURCES

- See ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Y chromosome DNA test,” rev. 30 Oct 2013. ↩

- “If two men share a surname, how should the genetic distance at 37 Y-chromosome STR markers be interpreted?,” Frequently Asked Questions, Family Tree DNA (http://www.familytreedna.com/faq : accessed 9 Nov 2013). ↩

- See ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Autosomal DNA,” rev. 7 Oct 2013. ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Autosomal DNA testing,” National Genealogical Society Magazine, October-December 2011, 38-43. ↩

- See ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Recombination,” rev. 20 Jul 2013. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

I’m sure you can’t do this with any testing company tools, but with a mere 15 colors you could map out every sharing combination of the four siblings across the chromosome. Got crayons?

Chromosome mapping is going to be great fun, Ruy… and just wait ’til I get that fifth sibling…

Thanks Judy. You do great DNA articles along with everything else.

I’d love to hear you review DNAme as it looks like a lesser known potential 4th player in the genealogy DNA test world. $85 for all 3 tests sounds too good to be true.

I just got the testing finished for my 2 living grandparents and one parent, but I’m really hoping for some kind of bulk discount on tests to come out before I do the siblings. We will see whether a deal comes or my patience breaks first.

If you had 2 males to choose from for y dna would you rather test the older one?

I hope you’ll write about all this. Thanks! 🙂

Thanks for the kind words, Michael. Your questions have been added to the queue — but a quick answer to the easy one: for YDNA, it doesn’t matter what generation male you test as long as the male is in the direct male line. It’s only with autosomal DNA that the generation matters.

JUDY

I think what this shows is that (to a high degree of probability) all four of your aunts and uncles are closely related.

Somehow, that is not a surprise. Back when I was in the work-a-day world we called such a result “Quantifying the obvious”.

But I guess … if you had the results for some random person, that their data would not have shown such a high degree of similarity. Do I have that right?

Seems to me that to a chart with some random folks thrown in would make this point.

Maybe next time.

DICK FOLKERTH

ps I’m not trying to be picky. Just trying to help.

The point isn’t that unrelated folks don’t match. It’s that even people who are very closely related will not match in every particular.

Thank you for explaining that. I do understand it. But what’s more important to me in terms of finding whether or not a particular person is likely to be a relative of mine (of any degree) is:

Did the autosomal test show Trisha as a relative of David, Carol & Mike, despite the fact that they share very little on Chronmsome 4? What degree of relationship did it suggest?

Helen Gardner

Oh yes, it sure did. Trisha is a full sibling to David, Carol and Mike and is so shown by the autosomal test.