A tale of two deeds

They are recorded one after the other in the minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions.

The place was Burke County, North Carolina. The time, the January session of court, 1807.

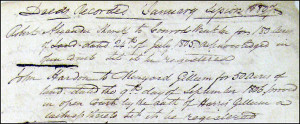

Robert Alexander Sheriff to Conrad Winkler for 180 Acres of Land. dated 24th of July 1805. Acknowledged in open Court Let it be registered.1

And the second reads:

John Hardon to Minyard Gillum for 50 Acres of land. dated the 8th day of September 1806. proved in open Court by the oath of Harris Gillum a witness thereto Let it be registered.2

Neither recorded deed exists today. Burke County’s deed books fell victim to that minor disagreement known as the Civil War.3

So… what’s the difference between these two?

In both cases, somebody had to come into court and present the deed for recording. The key difference is just who that person was. And the clue to look for is the way the clerk recorded these events: one of these deeds was acknowledged, and the other was proved.

In the law, the term “acknowledgement” has a very specific meaning. It is “[t]he act by which a party who has executed an instrument of conveyance as grantor goes before a competent officer or court, and declares or acknowledges the same as his genuine and voluntary act and deed.”4

By using that specific word, the clerk of the court was saying that Robert Alexander was physically present in court and admitted that the deed was valid. So any time you see a court record that says your ancestor acknowledged a deed or bill of sale or any other legal document, you’ve nailed that ancestor’s feet to that courthouse floor at a particular time. He was there.

By contrast, when the court record says a deed or a will or some other legal document is proved, it’s always by a witness. The purpose is to “establish the genuineness and due execution of a paper, propounded to the proper court or officer.”5

Sometimes, as in the case of the Gillum deed, it’s a witness to the actual document — Harris Gillum was identified in the record as “a witness thereto” when it came to the deed. So you have Harris’ feet nailed to the floor twice: once in the courthouse at that January 1807 term of court, and, earlier, on the 8th of September 1806, when John Hardon signed the deed.

You’ll also sometimes see a lengthier proof statement when the person testifying didn’t witness the actual document, but testifies about the handwriting or other evidence.

And in all of these cases, the language tells you something about the people involved. If it’s an acknowledgment, it gives you evidence that the person was there at the courthouse on a particular day. If it’s a proof, it may be by a witness to the document — giving you evidence not just of physical presence when the document was signed but of a relationship between the witness and the people who did sign the document. Often the witnesses were family; at a minimum, they had to have been in the neighborhood.

And it may give you leads to other information as well. When a document isn’t acknowledged, it’s always a good idea to ask why not. It’s a safe bet that a will won’t be acknowledged — the testator is (or ought to be!) dead when it’s presented to the court. But what about a deed? Did the grantor die? Leave town? It’s another clue to follow as we chase our ancestors through the records books.

SOURCES

- Minute Book, Burke County, North Carolina, Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions, January 1804 – April 1807, Part II, Minutes of January Session 1807, unpaginated; call no. C.R.014.301.4; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Betsy Dodd Pittman, “What Happened to Burke County Records?”, Burke County Genealogical Society Journal, Vol. VII, No. 3 (September 1989), at p. 70. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 19, “acknowledgment.” ↩

- Ibid., 959, “prove.” ↩