First among equals

So The Legal Genealogist was sitting there poking around in old records one more time and came across a reference in a Vermont town record to a title for an official that was a new one.

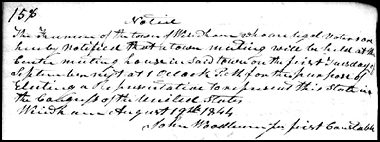

The record is in the minutes of the town of Windham, Windham County, Vermont; it’s dated 19 August 1844. In the record, John Woodburn gave notice to all legal voters of the town of Windham that a town meeting was to be held on the first Tuesday of September “for the purpose of electing a representative to represent this State in the Congress of the United States.”

The record is in the minutes of the town of Windham, Windham County, Vermont; it’s dated 19 August 1844. In the record, John Woodburn gave notice to all legal voters of the town of Windham that a town meeting was to be held on the first Tuesday of September “for the purpose of electing a representative to represent this State in the Congress of the United States.”

And that record identified John Woodburn as “the first constable.”1

So… what’s a first constable?

The term constable is an old one in the United States, having been brought over to the colonies as part of British common law.2 The office of the constable in Vermont is of constitutional origin, appearing for the first time in section 17 of the Constitution of 1777 which required the freemen of each town to deliver their votes to the constable “who shall seal them up, and write on them, votes for the Governor, and to deliver them to the representative chosen to attend the General Assembly.”3

As early as 1792, references appeared to the office of first constable, such as the reference in an early court case to a warrant from the State Treasurer “to the first constable of South Hero to collect a halfpenny on each acre of land.”4 The use of the term was established enough by 1796 that a report from the Treasury Department to Congress on Direct Taxes included a representation that, in Vermont, “the first constables are collectors of taxes, and are chosen by the inhabitants of the respective towns, which are responsible for their conduct.”5

As of 1840, Vermont state law provided that “the first constable, elected in each town, shall be the collector of state taxes for such town.”6 The law further provided that “the first constable, chosen annually in each town, shall levy and collect all the state and other taxes required by law.”7

So… what’s with the first constable thing anyway?

Well, it turns out that there can be more than one constable in a Vermont town. They’re independent of each other — one won’t be the other’s boss. But only the one selected as first constable collects the taxes.8

But what’s really fun is finding out what else Vermont’s early constable was supposed to do. In 1779, the Vermont Legislature passed a law setting out just what was expected, and it provided that “one constable in each respective town in this state, shall be chosen to levy and gather the state’s tax in such town.”9 But that was just the beginning.

The duties of the constables set out in the statute were many. They were expected to serve and execute writs, and to head out and organize pursuits or hue-and-cries after “murderers, peace breakers, thieves, robbers, burglars, and any other capital offenders.”10

But they were also to apprehend “such as are overtaken with drink — guilty of profane swearing, Sabbath-breaking, lying; also vagrant persons, and unseasonable night-walkers.”11 The statute didn’t suggest what the season for nightwalking might be.

And they were also supposed to

make a diligent search, throughout the limits of their town, upon the Lord’s Days, … for such offenders as shall lie tippling in any inn, or house of entertainment, or private house, excessively, or unseasonably; and after such as retail strong drink without license; and also warn all those that frequent public houses, and spend their time there idly, to forbear; and also warn all those that keep such houses, not to suffer any such persons in their houses: and to make due presentment of all breaches of the peace (coming within their knowledge0 to some authority proper to receive the same, once in every month. …12

There were penalties if the constable didn’t act — but the constables weren’t entirely on their own. In order to make sure they had the manpower they needed, the law imposed fines on those who didn’t help out. A fine of five pounds was assessed on any person “who shall refuse at any time to assist any constable in the execution of his office.” And if the person “willfully, obstinately, or contemptuously refused to assist such constable,” the fine was 10 pounds.

And you thought the law was boring?

Not with constables out chasing down nightwalkers…

At least the unseasonable ones…

SOURCES

- Windham, Vermont, Town & Vital Records, 3:158, election notice, 19 August 1844; digital images, “Vermont, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1732-2005,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “North Carolina’s constables,” The Legal Genealogist, posted date (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 6 Mar 2013). ↩

- Constitution of 1777, Vermont State Archives (http://vermont-archives.org/ : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩

- Doe v. Whitlock, 1 Vt. 305 (1802). ↩

- U.S. Congress, American State Papers: Documents Legislative and Executive of the Congress of the United States, 38 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1832-61), class III, Finance (5 vols.), 1:418; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩

- § 59, The Revised Statutes of the

State of Vermont Passed November 19, 1839 (Burlington : Chauncey Goodrich, 1840), 93; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩ - Ibid., §64. ↩

- See generally “Opinion 12. Second Constable Is Not Assistant to First Constable,” Vermont Secretary of State, Opinions, Vol. 3, No. 8 (http://www.sec.state.vt.us/secdesk/opinions : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩

- “An Act Directing Constables in their office and Duty,” in Vermont State Papers … and the Laws from the year 1779 to 1786, inclusive (Middlebury, Vermont: J.W. Copeland, printer, 1823), 332; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 24 Nov 2013). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 332-333. ↩

Great example of how to follow up on a term found in a historical document, Judy. Of course, I am not partial to it being a Vermont example. I’m currently reading a new book by Vermont attorney and historian Paul S. Gilles, Uncommon Law, Ancient Roads, and Other Ruminations on Vermont Legal History. I think you’d enjoy it.

Sounds like a great book, Cathi! I’ll add it to my list!