Common law marriages and pension law

In a comment to yesterday’s blog post about common law marriage in Alabama, reader Greg Lovelace mentioned that he was researching another Alabama couple whose common law marriage dated back to just after the Civil War.

“After the husband’s death, his widow made two separate applications for a Union Civil War pension. Both appear to have been denied. There are three witness affidavits included in the pension applications, and each one has the notation ‘cohabitation’ written in the margin,” Greg wrote.

“After the husband’s death, his widow made two separate applications for a Union Civil War pension. Both appear to have been denied. There are three witness affidavits included in the pension applications, and each one has the notation ‘cohabitation’ written in the margin,” Greg wrote.

So his question was, “Did the Pension Board recognize common-law marriages as legal in 1867?”

And the answer is, yes, they did.

The initial pension act passed for purposes of Civil War pensions was in July 1862. It provided for a pension to any soldier or sailor who, after 4 March 1861, had been “disabled by reason of any wound received or disease contracted while in the service of the United States, and in the line of duty.”1 It also provided for the same pension to be paid to the widow of any soldier or sailor who died from the same causes.2

What the statute didn’t do was define the word “widow.” That’s generally been a term defined by the laws of the states, not the laws of the federal government. And, in general, it was understood to include common-law marriages.

In fact, from the early 1800s, court cases had determined that cohabitation plus the couple holding themselves out as husband and wife would be sufficient to recognize a marriage, even for purposes of receiving a pension.3 By 1878, even the U.S. Supreme Court had held that there was no legal bar to recognizing a common law marriage.4

Having said that, it’s important to note that there was a long history by the time of the Civil War of efforts by the Pension Office to require far more proof of marriage than the courts at the time would require. Pension office instructions to applicants for Revolutionary War pensions required record proof “whenever it can be obtained”5 — even if, often, it couldn’t be obtained.

And the examiners within the Pension Office had a habit of going out of their way to require levels of proof of a marriage that would never have been required in a court of law at the time.6

By 1846, Congress had had enough of complaints by applicants and had passed a law providing that a widow was not required to submit any further evidence “other than such proof as would be sufficient to establish the marriage between the applicant and the deceased pensioner in civil personal actions in a court of justice.”7

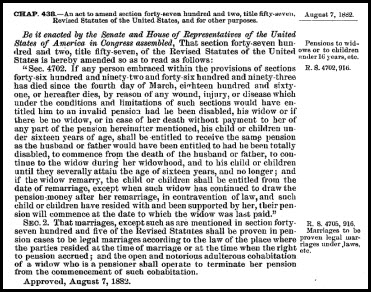

And in 1882, Congress made it clear that it was state law, not federal law, that was to provide the rule of decision in determining if a marriage was valid — and what proof would be required. It amended the pension law to provide specifically that “marriages … shall be proven in pension cases to be legal marriages according to the law of the place where the parties resided at the time of marriage or at the time when the right to pension accrued.”8

As a result of all these provisions, proof of a common law marriage was acceptable when the marriage occurred in states which recognized common law marriage, and the notation in the margins of the affidavits in Greg’s case may suggest nothing more than a clerk’s indication that the affidavits attested to the fact of cohabitation (rather than, for example, being affidavits from witnesses who attended a ceremonial marriage).

Proof of cohabitation was particularly important in cases where the soldiers or sailors had been freedmen. Special provisions were included in the Civil War-era legislation to provide for such cases since many of them could not have married legally under the laws of the states where they had lived. In 1864, Congress allowed their widows pensions “without other proof of marriage than that the parties had habitually recognized each other as man and wife, and lived together as such” for at least two years before the man enlisted “to be shown by the affidavits of credible witnesses.”9

In 1866, Congress changed the provision and allowed pensions for their widows “without other evidence of marriage than proof, satisfactory to the Commissioner of Pensions, that the parties had habitually recognized each other as man and wife, and lived together as such.”10

It followed that with a further resolution allowing bounties and other benefits based on evidence that the soldier “and the woman claimed to be his wife or widow were joined in marriage by some ceremony deemed by them obligatory, followed by their living together as husband and wife up to the time of enlistment.”11

So… yes, for all soldiers and sailors and their widows, common law marriage was enough for a pension, if state law allowed or if the serviceman was a freedman. And to prove common law marriage, multiple affidavits were usually submitted, meaning lots of records in the pension files to the delight of today’s genealogists.

SOURCES

- §1, “An Act to grant Pensions,” 12 Stat. 566 (14 July 1862). ↩

- Ibid., §2. ↩

- See e.g. Fenton v. Reed, 4 Johns. 52, 53 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1809). ↩

- Meister v. Moore, 96 U.S. 76, 80-81 (1878). ↩

- “Rules of Evidence in Widows’ and Orphans’ Claims,” in Pension Laws Now in Force, H.R. Doc. No. 25-118 (2d Sess. 1838). ↩

- See generally Kristin A. Collins, “Administering Marriage: Marriage-Based Entitlements, Bureaucracy, and the Legal Construction of the Family”, Vanderbilt Law Review 62 (May 2009): 1086-1167. ↩

- §2, “An Act making Appropriations for the Payment of Revolutionary and other Pensions…, and for other Purposes,” 9 Stat. 5 (7 May 1846). ↩

- §1, “An act to amend section forty-seven hundred and two, title fifty-seven, Revised Statutes of the United States, and for other purposes,” 22 Stat. 345 (7 Aug 1882). ↩

- §14, “An Act supplementary to an Act entitled ‘An Act to grant Pensions,’ approved July fourteenth, eighteen hundred and sixty-two,” 13 Stat. 387, (4 July 1864). ↩

- §14, An Act supplementary to the several Acts relating to Pensions, 14 Stat. 56 (6 June 1866). ↩

- §2, “A Resolution respecting Bounties to Colored Soldiers, and the Pensions, Bounties, and Allowances to their Heirs,” 14 Stat. 358 (15 June 1866). ↩

My g-g-gf Henry, a Civil War vet, died in 1917. Sarah, his “widow” tried to claim his pension. They lived in Pennsylvania, but she claimed that they were married in West Virginia. She could not provide proof of their marriage. This led to a very thick pension file! I think the pension was denied in 1920 because PA did not recognize it, and because her first husband (who divorced her because of her relationship with Henry) outlived Henry by more than a year. A public tree (The Amos-Leighty Tree on Ancestry.com) has a transcription of the decision at http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/4697012/person/-1424447706/mediax/2?pgnum=1&pg=0&pgpl=pid%7CpgNum

A perfect example of state law providing the rule of decision! Thanks for posting that, Linda! (Fun case!)

(Oh, it probably didn’t help her case when Henry completed a questionnaire while living in the National Soldiers Home in Dayton, OH, saying that he was “not never married but onse” and that his wife, Rebecca, who divorced him, had died. I believe there was also an affadavit from Henry’s daughter, Daisy, who says her father said on his deathbed that he was never married to Sarah. This must have been the cause of much dismay to his children, to grill him on his deathbed as to whether he ever married Sarah.

Yeah, that wouldn’t have helped at all!

My cousin got married in Montana a few years ago. She was married by her brother, who is not a minister, judge, or other person normally allowed to perform marriages. My aunt told me that Montana has a law allowing any Montana resident to perform one marriage. Is this related to common law marriage law?

Montana has some interesting marriage laws, but allowing a marriage to be legally solemnized by any Montana resident isn’t one of them. My guess is that this was instead a marriage technically under Section 40-1-311 of Montana law, and the brother simply handled the ceremony.

Thanks very much for this exploration.

I was thinking about all the records destroyed during wars and by fire, flood and other means. Then I remembered the instance where a Mohawk Valley, NY pastor was asked to come up with a marriage record for a Revolutionary War veteran’s widow. He wrote a rather peeved letter to the Pension office, pointing out that the Government had provided little help to protect the Valley during the War, and church records had been destroyed. I now wish I had made a long-lasting notation as to which pension file this was in!

I can’t help but think of the modern version of these dilemmas: all the pension applications from servicemen and servicewomen’s spouses that were/are/will be adjudicated based on whether or not their particular state of residence recognized same-sex marriages or not, and during which time period. At the moment, with DOMA now struck down, the Pentagon says they will recognize all of these marriages for the sake of benefits, as long as they were formally performed in a state where it is legal. But what about the possibility of retroactive recognition, as the government once extended to slaves who were also denied marriage recognition? How would one even go about proving one was essentially common-law married to a now-deceased vet if the entire marriage had to be kept hidden?

(My first cousin three times removed, who died at an advanced age just a few years ago, met his husband while they were both serving together in the Merchant Marine during WWII. They were together for thirty years until his husband’s death from a heart attack. Obviously no benefits nor pensions awarded to them, alas.)

The fragmentation of laws and organizational/governmental policies recognizing marriage today means that the genealogists of the future are going to have a really interesting time studying this period of history.

Oh, you are so right that this is going to be a time that poses interesting challenges for tomorrow’s researchers, Brooke — and in so many ways. But I regret to say that I believe the proof difficulty you suggest is going to be the reason why retroactive recognition isn’t going to be allowed here — which makes legal marriage everywhere so very important.

I am a little late in reading this post….by 3 years. I have just started flipping the pages of my husband’s great great uncle’s CW widow pension file. Oh, the juicy stuff has started flowing, and I am not through page 12 of 220. Common law marriage, yep, cohabitation, yep, a legal marriage to the vet, yep, a congressional hearing against the filing attorney for fraud, YEP! Two illegitimate children and one legal, YEP YEP YEP. Isn’t it fun to browse the sins of others? Thanks for posting your topic, Pension and Marriage.

Pension files are fabulous resources, aren’t they? 🙂