Required reading for genealogists

If you spent the last 24 hours in a facility without electricity or even a cellphone, let The Legal Genealogist bring you up to date:

12 Years A Slave won the best picture award last night at the Oscars.

Lupita Nyong’o took the best supporting actress award for her portrayal of the slave girl Patsey and John Ridley won for the screenplay.

Lupita Nyong’o took the best supporting actress award for her portrayal of the slave girl Patsey and John Ridley won for the screenplay.

This cinematic depiction of slavery has focused attention on the strength of our African-American community — its survival in the face of raw and unrelenting brutality — and it is above all else a story with the power of truth.

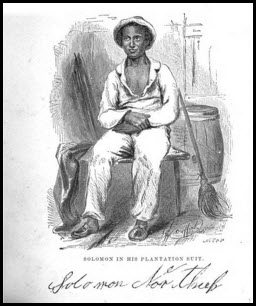

This isn’t fiction. Solomon Northup lived. You can find him and his family on the 1840 census of Saratoga County, New York, where he was recorded in the Town of Saratoga Springs as a free man of color, aged 30-40 years.1

It was just one year later when he was kidnapped from Washington, D.C., and sold as a slave. You can read his own account of that kidnapping and its aftermath. It’s a memoir called Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River, in Louisiana, and it’s available on Google Books.2

You can see the manifest of the brig Orleans, bound from Richmond in 1841, that carried Northup, under the name “Plat Hamilton” — describing him as male, age 26, height 5 feet 7 inches, color “yellow.”3

You can find him on the 1855 New York State census after he was rescued from slavery, living in Warren County, New York, with his wife Anne and son Alonzo.4

With just a little effort, today, you can find Solomon Northup’s story. It’s a story worth reading, in its long form, and with all its constituent pieces.

What you won’t find, at least not yet, is the story of Patsey, the slave girl, after Solomon Northup was rescued.

And that, by itself, is a story worth reading.

Because, in so many ways, it is the story of today’s African-American genealogists and their own struggles in trying to find their roots.

Katie Calautti, a writer for the magazine Vanity Fair, set out to find the answer to Patsey’s question, the one she asked as Solomon Northup was leaving the plantation a free man again — her heart-wrenching cry: “What’ll become of me?”

And even with help and input from some of America’s top experts in Louisiana research, including genealogist Elizabeth Shown Mills, Calautti couldn’t find out what happened to Patsey.

By the time the article was due, she had reached the same point so many of our colleagues reach in researching their own enslaved families: “How can it be this hard to find one woman?” she wrote. “The question seems as deceptively simple as Patsey’s, but the difficulty in answering proves emblematic of the lost histories of many slaves.”5

Solomon Northup’s story.

What can be found of Patsey’s story.

The story of research into slave ancestors.

Required reading for us all.

SOURCES

- 1840 U.S. census, Saratoga County, New York, p. 262 (stamped), Solomon Northup; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 2 Mar 2014); citing National Archive microfilm publication M704, roll 336. ↩

- Solomon Northup and David Wilson, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, from a Cotton Plantation Near the Red River, in Louisiana (New York : Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 2 Mar 2014). ↩

- “Celebrating the life of an ancestor who was ‘12 Years A Slave,’” National Archives Prologue blog, posted 17 Dec 2013 (http://blogs.archives.gov/prologue : accessed 2 Mar 2014). The manifest itself can be seen here. ↩

- 1855 New York State census, Warren County, New York, page 14 (penned), dwelling 110, family 126, Solomon Northup; Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 2 Mar 2014); citing New York State Archives microfilm. ↩

- Katie Calautti, “‘What’ll Become of Me?’ Finding the Real Patsey of 12 Years a Slave,” Vanity Fair, posted 2 Mar 2014 (http://www.vanityfair.com : accessed 2 Mar 2014). ↩

12 Years a Slave very much deserved its Oscar for best picture. It is a very powerful and moving film which I think everyone ought to see. I find it quite extraordinary that no has been able to find a record of Solomon Northrup’s death or burial, even though he died at a time when death records and burial records should surely have been available.

We weren’t quite as up to date with death records here on our side of the Atlantic, Debbie. There are record gaps here right into the early days of the 20th century.

These are the complexities that African American Research deal with on a daily basis and not understood by the wider Genealogy community. Our techniques are somewhat different. Documentation is lost and has been stolen and hidden in many homes across this Country. It was a intentional confusion. We, now all must be a part of piecing our lost History together. If the African American History is not just OUR respondsibility. It’s the Whole Genealogy Community as well. If that part of our History is not Spoken or Told everyone else’s story is not complete.

I think they’re understood more than you might suspect, True, and as DNA shows more and more than we’re all cousins at a genetic level the understanding is growing by leaps and bounds.

When I first heard of the movie “12 Years a Slave”, I dug out my “Roots” DVD’s, just to refresh my memories. I didn’t realize it was about 8 hours long, my genealogy friends and I watched 4 hours one night and 4 hours the next. Next week a group of us are going to see “12 Years a Slave”, for some of us this will be the second time.

Roots was certainly one of the most powerful television presentations ever done by that time, Gus. But because of the vast scope and the need to comply with the mandates of the TV medium, I suspect 12 Years A Slave may end up as a more powerful piece overall. You’ll have to let us know what you think.

Did the descendants of Solomon Northrup derive any monetary gain from the movie, 12 Years A Slave? Most likely the answer is no.

Should had Brad Pitt, Steve McQueen, Lupita, Searchlight Pictures and others at least set up an endowed scholarship fund Northrup descendants? The consensus “do right” answer to that question is most likely yes if they truly wished to honor the legacy and memory of Solomon Northrup.

However, I will give credit to Lupita Nyong’o for attending a Northrup family reunion in NY in July 2013 where she said: “We had this responsibility to bring these people back to life for the wider world to see.” With her acting ability and sentiments such as this she deserved the Oscar she won.

Like Lupitia, some times, each of us needs a little piece of soap to remind us to volunteer our talents to assist an African American in need of Genetic Genealogy guidance and expertise.

http://saratogacharacters.blogspot.com/2013/07/honoring-solomon-northup.html

http://sketchflashmob.wordpress.com/tag/solomon-northrup/

http://blogs.archives.gov/prologue/?p=13029

The story was clearly in the public domain, so I suspect the answer is no. No more than Abraham Lincoln’s relatives would have benefited from a movie made today about his life.

Spoken eloquently by a person seeing the world narrowly with legal tinted glasses.

I am not talking about what’s legally right here … but rather what is morally right.

And specifically what is morally right and just for Northrup’s descendants, some of whom are note below. I think they may have a different opinion with what portends to be “just” and being cast 100% in the public domain versus being “morally just” and beneficial for their private family domain.

Granted that this is a human soul story of Solomon Northrup, a deceased African American person, whose story indeed has long been in the public domain.

However, the descendants of Henrietta Lacks, also a deceased African American person, with a human tissue story, did recently obtain some moral justice and financial benefits.

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/08/130816-henrietta-lacks-immortal-life-hela-cells-genome-rebecca-skloot-nih/

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/gallery/12-years-a-slave-portraits-683439

Apples and oranges. The Lacks case was one where information affecting living people — children of Henrietta Lacks — was disclosed without their knowledge or permission. Without question they needed to be brought into the decision-making process — and that’s all that was done. Absolutely no money was provided to the Lacks family, just the right to have some control over dissemination of private information. That’s a huge difference from the Northup case, where the nearest living relatives are (I believe) great great grandchildren.

OK. Would you an out of court settlement involving a Apples – Oranges – Pears?

“Some Lacks family members raised the possibility of financial compensation, Collins says. Directly paying the family was not on the table, but he and his advisers tried to think of other ways the family could benefit, such as patenting a genetic test for cancer based on HeLa-cell mutations. They could not think of any. But they could at least reassure the family that others would not make a quick buck from their grandmother’s genome, because the US Supreme Court had this year ruled that unmodified genes could not be patented. Lacks-Whye says that the family does not want to dwell on money — and that her father has often said he “feels compensated by knowing what his mother has been doing for the world”. https://legalgenealogist.com/blog/2014/03/03/slaverys-stories/

Now back to the Solomon Northrup case. Do you think a scholarship fund for his descendants is one of the morally right things to do?

Your source confirms what I understood to be the case: no money involved in the Lacks case at all.

And what I do or don’t think is morally right is utterly irrelevant. My personal opinions don’t drive business decisions by others.