The curious case of Jacob P. Dunn

There’s no doubt about it: sometimes the law is just plain confusing.

And there’s good reason why reader Patricia Taylor was a little bit puzzled by the language of a legal record she came across about a man she’s trying to nail down as someone who is or isn’t sitting there on a branch of her family tree.

And there’s good reason why reader Patricia Taylor was a little bit puzzled by the language of a legal record she came across about a man she’s trying to nail down as someone who is or isn’t sitting there on a branch of her family tree.

The question is whether the record she found relates to her family member — and whether the case itself was a state case or a federal case.

Since that’s a topic The Legal Genealogist has been looking at this week,1 let’s go on to this particular little weirdness of the law…

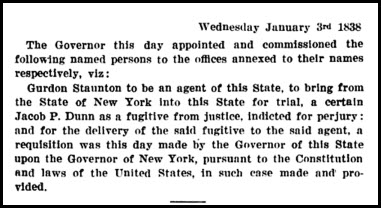

What Patricia found was a summary of an action by Governor Joseph Ritner of Pennsylvania on Wednesday, the third of January 1838. The summary read:

The Governor this day appointed and commissioned…

Gurdon Staunton to be an agent of this State, to bring from the State of New York into this State for trial, a certain Jacob P. Dunn as a fugitive from justice, indicted for perjury: and for the delivery of the said fugitive to the said agent, a requisition was made this day by the Governor of this State upon the Governor of New York, pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the United States, in such case made and provided.2

The name matches, you see — Jacob P. Dunn — and Patricia’s Jacob P. Dunn did live in Pennsylvania in the 1830s, and was born in New York around 1779. But to find out more about this Jacob P. Dunn, she needs to look at the records of this particular case.

But where are they?

With all the references here to federal law, it’s easy to be confused as to what kind of case this is. So let’s start by talking about what’s going on here.

This particular Jacob P. Dunn was indicted — charged with a crime3 — in a Pennsylvania state court. The particular charge was perjury — lying under oath.4 At the time this record was made, in January 1838, this Jacob was in New York, and Pennsylvania wanted him back to stand trial.

But Pennsylvania didn’t have any authority to make somebody come to Pennsylvania from another state like New York. The only way it could force the person to come back was to get New York to go along. Remember, these are early days for the United States, and states were particularly protective of their own rights and privileges. So one State had to ask another State to send the guy back.

And that process goes by the generic term of extradition. Complicating this, of course, is the fact that the word extradition is totally absent from this particular record.5

In fact, there are a lot of words that might be — and often are — used in these kinds of cases.

• Extradition is defined as the “act of sending, by authority of law, a person accused of a crime to a foreign jurisdiction where it was committed, in order that he may be tried there.”6

• Rendition is the word often used instead of extradition when describing the process between two states, as opposed to between two nations.7

• Requisition — what the Pennsylvania Governor made to the Governor of New York — is defined as the “formal demand by one government upon another, or by the governor of one of the United States upon the governor of a sister state, of the surrender of a fugitive criminal.”8

But if this is all between the two Governors, why all the references to federal law? That’s because that’s where the authority is to make the request in the first place: “By the constitution and laws of the United States, fugitives from justice may be demanded by the executive of the one state where the crime has been committed from that of another where the accused is.”9

The Constitutional provision referenced in the definition, and in the record Patricia found, provides that:

A person charged in any state with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee from justice, and be found in another state, shall on demand of the executive authority of the state from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the state having jurisdiction of the crime.10

And the laws of the United States to put that into affect had been around since 1793:

whenever the executive authority of any state in the Union, or of either of the territories northwest or south of the river Ohio, shall demand any person as a fugitive from justice, of the executive authority of any such state or territory to which such person shall have fled, and shall moreover produce the copy of an indictment found, or an affidavit made before a magistrate of any state or territory as aforesaid, charging the person so demanded, with having committed treason, felony or other crime, certified as authentic by the governor or chief magistrate of the state or territory from whence the person so charged fled, it shall be the duty of the executive authority of the state or territory to which such person shall have fled, to cause him or her to be arrested and secured, and notice of the arrest to be given to the executive authority making such demand, or to the agent of such authority appointed to receive the fugitive, and to cause the fugitive to be delivered to such agent when he shall appear: But if no such agent shall appear within six months from the time of the arrest, the prisoner may be discharged. And all costs or expenses incurred in the apprehending, securing, and transmitting such fugitive to the state or territory making such demand, shall be paid by such state or territory.

…any agent, appointed as aforesaid, who shall receive the fugitive into his custody, shall be empowered to transport him or her to the state or territory from which he or she shall have fled. …11

Now that sounds pretty definitive, doesn’t it? If one State asks, it “shall be the duty” of the other State to arrest the dude and hand him over, right?

Um… not exactly.

See, not all the States regarded the same sorts of things as criminal. And the first time the issue of this extradition clause came up before the U.S. Supreme Court, it came up in the context of a man wanted in Kentucky for helping a slave girl escape. Kentucky demanded that Ohio send the guy back for trial; Ohio’s Governor William Dennison said no; Kentucky asked for a court order making Dennison send him back.

The Supreme Court refused to grant the order. It said the words “shall be the duty” only meant a moral duty, not a legal duty, and it concluded that: “If the Governor of Ohio refuses to discharge this duty, there is no power delegated to the General Government, either through the Judicial Department or any other department, to use any coercive means to compel him.”12

So the bottom line here was that Pennsylvania could ask to have the guy sent back, New York was supposed to say yes and hand him over to the agent — the Gurdon Staunton appointed by Governor Ritner in the order — but even though federal law said that, federal courts kept a hands-off approach if the two States got into a squabble.

In other words, the records of the court case and of this whole extradition-rendition process — if they still exist today — are going to be in State records, and not in federal records.

First place to look: the archival records of the two Governors.

The Pennsylvania State Archives, in Record Group 26, Records of the Department of State, series 26.11, Extradition File, 1794-1890, 1906-1914, holds files described this way: “Extradition orders signed by the Governor of Pennsylvania requesting other Governors to extradite prisoners from their states to the Commonwealth and letters from the Governors of other states requesting extradition of prisoners from Pennsylvania. Information generally given is date of extradition order, name of prisoner, nature of the crime alleged, and signature of the Governor or others requesting the extradition.”13 If it survives, the Dunn extradition file may be there.

The papers of the then-New York Governor William H. Seward generally aren’t in the New York Archives because he went on to serve as a United States Senator and as Secretary of State under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson.14 (Think Seward’s Folly here — the purchase of Alaska from Russia.)

Instead, most of Seward’s papers are held by the library at the University of Rochester, and have been microfilmed there. And among them… files of extradition requests — though it isn’t clear whether these were incoming, or outgoing, or both.

If the records of either Governor still exist for this case, the file should contain a copy of the indictment — remember, that’s what the federal law required — and that will lead Patricia to the specific court where the indictment for perjury originally came from and, we can hope, the file there that says whatever happened to Jacob P. Dunn.

Extradition. Rendition. Requisition. And I haven’t even mentioned removal yet…

Another day, another blog post…

SOURCES

- See Judy G. Russell, “For the Record(er),” The Legal Genealogist, posted 11 Mar 2014 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 13 Mar 2014). Also, ibid., “A matter of diversity,” posted 12 Mar 2014. ↩

- Gertrude MacKinney, editor, Pennsylvania Archives, ninth series, vol. 10 (Pa. Dept. of Property and Supplies, 1935), 8447; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 13 Mar 2014). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 616, “indictment.” ↩

- Ibid., 890, “perjury.” ↩

- And lawyers wonder why people think the law is confusing… ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 13 Mar 2014), “extradition.” ↩

- See e.g. CRS Annotated Constitution, Article IV, html version reprinted at Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School (http://www.law.cornell.edu/ : accessed 13 Mar 2014). ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 1027, “requisition.” ↩

- Bouvier, A Law Dictionary, “extradition.” ↩

- Article IV, §2, clause 2, Constitution of the United States. ↩

- §§1-2, “An Act respecting fugitives from justice, and persons escaping from the service of their masters,” 1 Stat. 302 (12 Feb 1793). ↩

- Kentucky v. Dennison, 65 U.S. 66, 107, 109-110 (1860). ↩

- Series 26.11, Records of the Department of State, Series Descriptions, Pennsylvania State Archives (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us : accessed 13 Mar 2014). ↩

- Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.com), “William H. Seward,” rev. 13 Mar 2014. ↩

I don’t know if they still are, but those Pennsylvania Archives you mention used to be available at Fold3. Apparently there was an agreement that Fold3 could publish those records but could not charge for them. So you didn’t have to be a member of Fold3 to access them. I spent many hours going through them until Fold3 changed its “workings” and it became more difficult to search and less accurate. Then I decided to look to other sources.

The published books still are on Fold3, Mary Ann. It’s annoying to have a set of books called the Pennsylvania Archives, and a repository called the Pennsylvania Archives with the original records.

Thanks, Judy! All I know is that I got quite a bit of the history of my early (1662 – mid-1700’s) Hendricks/Hendrix forebears from the archives at Fold3! I knew they were probably transcriptions, but as close as I might ever be to the originals.

Cheers,

Mary Ann