The not-so-obvious term

Okay, this one seems like it should be a no-brainer, right?

We all know what probate means.

I mean, seriously, we can’t hardly consider ourselves genealogists if we haven’t at least looked at probate records, now can we?

I mean, seriously, we can’t hardly consider ourselves genealogists if we haven’t at least looked at probate records, now can we?

So how ’bout if The Legal Genealogist tells you that, when you come across something that was probated, it may not be in a probate matter at all?

The issue came up when Jeff Thomas, a Baker cousin of mine, started looking at an ancestor who lived in South Carolina in 1784, but owned land in Georgia.

He’s trying to nail down this particular ancestor’s date of birth. There obviously aren’t any birth records for the 1700s in that part of the country, and there’s no family Bible or other record to shed light on it.

So Jeff is carefully and methodically working his way through the available documents surrounding this ancestor to see what light they might shed on the question.

In one instance, for example, this ancestor was named in his father’s 1746 will and identified as being under age. In the will, he received a particular piece of land, which he sold in 1756.

Aha! Major clues!

Jeff realized that, to have been named as a child — a minor — in his father’s 1746 will, his ancestor’s birth had to have occurred less than 21 years earlier.1 So he couldn’t have been born later [correction: earlier] than 1725.

He also realized that, for the ancestor to have sold the land on his own, he’d have had to have been of age. Otherwise, he’d have had to have a guardian sell it for him. And to be at least 21 in 1756, he had to have been born not later than 1735. So working with these two documents alone, the range of possible birth years has been narrowed down to somewhere between 1725 and 1735.

Fast forward all those years to the 1784 land transaction. The land was in Effingham County, Georgia. The buyer was described as a planter of Effingham County. But the seller — Jeff’s ancestor — lived across the border in Camden County, the old 96 District, in South Carolina. And, according to the records Jeff has, the deed was “probated in 96 Dist.” before a Justice of the Peace there.

So… was this in connection with a will — the kind of thing we’d expect to see when the word probated is used?

Probably not.

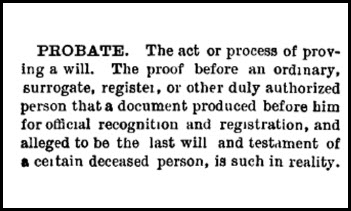

Yes, the typical way the word “probate” is used in the law is the way you see it in the image here today: it’s used to refer to the “act or process of proving a will. The proof before an ordinary, surrogate, register, or other duly authorized person that a document produced before him for official recognition and registration, and alleged to be the last will and testament of a certain deceased person, is such in reality.”2

But there’s a second meaning, especially when it’s used as a verb the way it is here.3 It also means — simply — “to prove” and the proof itself can be called “probation”: “The evidence which proves a thing. It is either by record, writing, the party’s own oath, or the testimony of witnesses.”4 Or, as Black’s Law Dictionary puts it, probation is the “act of proving; evidence; proof.”5

And to prove something, it means to “establish the genuineness and due execution of a paper, propounded to the proper court or officer.”6

So why was the term “probated” used in the land case rather than “proved”?

Part of the answer may come from local custom or the idiosyncracies of the justice of the peace before whom the proof was submitted.

But the biggest part probably comes from what else Black’s Law Dictionary says about probate. It notes that the word was also used “to designate the proof of his claim made by a non-resident plaintiff (when the same is on book-account, promissory note, etc.) who swears to the correctness and justness of the same, and that it is due, before a notary or other officer in his own state; also of the copy or statement of such claim filed in court, with the jurat of such notary attached.”7

Think about that for a moment. Though the context suggested is in actions for debt, it works perfectly well in a land deal as well:

• Buyer and seller from different states.

• Buyer needs to establish in his home state that the deed is valid.

• Seller (or seller’s witnesses) don’t want to travel to buyer’s state to prove the deed.

• Answer: seller or seller’s witnesses go to seller’s local court and prove it — probate it — there, and the proof gets sent along from one court to the other.

Probate. Not always what we think it is.

SOURCES

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Part 3: How old did folks have to be,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 20 Jan 2012 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 26 Mar 2014). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 945, “probate.” ↩

- Verb. You remember those, right? From grammar school? That’s “a word (such as jump, think, happen, or exist) that is usually one of the main parts of a sentence and that expresses an action, an occurrence, or a state of being.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.m-w.com : accessed 26 Mar 2014), “verb.” That much even I remember. Just don’t ask me to diagram a sentence. ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (1856); HTML reprint, The Constitution Society (http://www.constitution.org/bouv/bouvier.htm : accessed 26 Mar 2014), “probation.” ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 945, “probation.” ↩

- Ibid., 959, “prove.” ↩

- Ibid., 945, “probate.” ↩

“So he couldn’t have been born later than 1725.” Shouldn’t it be earlier than 1725?

You are sooo right. Corrected, and thanks.

Very interesting! After reading your post, I tried searching for the St. Clair, AL probate records (Edy Battles married William Steward – a brick wall)to see if there were any online and/or where to find them.

My “probate”search sent me to the St. Clair gov. site and this is what was on the page:

“Your St Clair County Probate Office is offering more convenience through our new secure online renewal system. The probate office has partnered with IMS Enterprises to provide you a way to renew your Auto tags conveniently from your computer. Please see special notes below on expired renewals and special tag issues. Please allow 7 to 10 days before the end of the month to receive your tags and/or decals and receipts”

HaHa! Not what I was expecting!

Cynthia

Not very helpful at all! 🙂 Try FamilySearch.org. It has digitized images from St. Clair County in two collections: Alabama, Probate Records, 1809-1985 and Alabama, Estate Files, 1830-1976.

Thanks, will do. I just thought it was funny that the probate office was for car tags, haha.

🙂