Among the earliest New Jersey birth records

It is always a joy for The Legal Genealogist — indeed, for any genealogist — to come across a record we didn’t know existed.

And it’s particularly a joy when the record reads like this:

I do declare that Elizabeth … now living in my family, daughter of William … & of Rachel …, is born the Eight of October in the Year Eighteen Hundred and five.

“The Year Eighteen Hundred and five.”

“The Year Eighteen Hundred and five.”

That’s not a typo.

Now, anyone who does New Jersey research knows that there aren’t any New Jersey birth records before 1848.

Except…

Except…

Except for the ones I learned about for the first time last night.

I had the pleasure of speaking at the New Jersey State Archives last night as part of the 2014 Exploring Your Jersey Roots lecture series, co-sponsored by the Archives, Genealogical Society of New Jersey (GSNJ), and Central Jersey Genealogy Club (CJGC). It’s part of the celebration of New Jersey’s 350th birthday.

And before I spoke, about researching our female ancestors, I got a personal introduction to some of the holdings of the Archives from the archivists on duty, with a promise for more when I return next week to talk about DNA.

That’s how I learned about these birth records. And they are stunning.

Not just because they exist, though that by itself is enough of a cause for joy.

But because, that record — the way I transcribed it above?

That’s not all it says.

Here’s the way it reads, in full, without the ellipses:

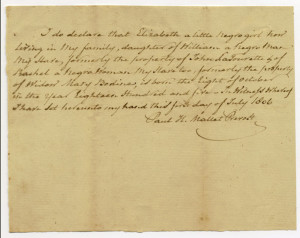

I do declare that Elizabeth a little Negro girl now living in my family, daughter of William a Negro Man My Slave, formerly the property of John LaTourette & of Rachel a Negro Woman My Slave too, formerly the property of Widow Mary Bodine, is born the Eight of October in the Year Eighteen Hundred and five.1

That’s right: that very earliest set of New Jersey birth records are the children of New Jersey slaves, born into freedom, under New Jersey law.

Here’s what the Archives says about this group of records:

The records in this series are the direct result of “An act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” passed by the New Jersey Legislature on 15 February 1804 (P.L. 1804, chap. CIV, p. 251). This law pronounced every child born to a slave mother after 4 July 1804 “free” at birth, but bound as a servant to the owner of the mother until the age of twenty-five for males and twenty-one for females. Any person entitled by the law to such bound service was required to file with the county clerk, within nine months of the birth of the child, a written certificate containing the name of the slave owner and the name, age and sex of the child. The clerk in turn was directed to record the information in a special book for this purpose. The penalty for neglecting to deliver such a certificate was $5 plus an additional $1 for each month of delinquency.2

And, it continues, there was a darker side to the law:

The law also allowed for the abandonment of such children by the owners of their mothers at the age of one year. In this case, the child would become a ward of the local overseers of the poor; the slave owner was required to file a notification of abandonment with the county clerk.3

These required birth records for one New Jersey county — Hunterdon County — have been digitized and are available online here. Not all of them are as complete as Paul H. Mallet-Prevost’s declaration of Elizabeth’s birth. Only a handful of the digitized set list the father; some don’t even name the mother, although most do. Some add the township or city where the child was born.

And these early birth records of the children of slaves survive from many New Jersey counties, and holdings of the Archives include records from the counties of:

• Bergen, 1804-1846 (microfilm)

• Burlington, 1804-1826 (text, 15 items)

• Essex, 1804-1843 (text, one volume; and microfilm)

• Middlesex, 1804-1844 (microfilm)

• Salem, 1800-1841 (microfilm, together with manumission records)

• Somerset, 1805-1830 (text, five items; and microfilm)

• Sussex, 1801-1835 (text, 15 items; and microfilm)

Wonderful records. Of a time and a people and a condition of slavery in the North that we often never knew about.

SOURCES

- Hunterdon County, New Jersey, Declaration of Paul H. Mallet-Prevost, 1 July 1806; Birth Certificates of Children of Slaves, 1804-1835, Series CHNCL004, New Jersey State Archives, Trenton; digital images, “Hunterdon County Birth Certificates of Children of Slaves,” New Jersey State Archives (http://www.nj.gov/state/archives/ : accessed 20 May 2014). ↩

- “Hunterdon County Birth Certificates of Children of Slaves,” New Jersey State Archives (http://www.nj.gov/state/archives/ : accessed 20 May 2014). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Applause !!

I’ve seen these in one county in Pennsylvania where I have read a few years’ worth of court entries in this same time period. I have thought it would be a great project to extract those for greater public accessibility. But then there are always a jillion worthy projects waiting to be done.

Time, time, time. It’s becoming the dirty four-letter word of our lives, isn’t it? Trying to get time to do everything we want to do!

Great to discover these records!! And, WOW, $5 was a hefty fine in 1805—and then another $ for each month of delinquency–a real penalty for most people!!

Sure makes it a lot more likely that the law was followed, doesn’t it?

Yes, I think we need to thank that part of the law for having these early records recorded so we can have them today!

You bet! 🙂

Wow! These records are incredible. What a find. To have a registered government document stating the full date of birth for a person of colour at that early time period in US history is amazing. Thanks for sharing, Judy.

They really are wonderful, aren’t they? Just stunning.

These records exist in all of the states that issued “gradual emancipation” laws, most notably New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Also see the James W. Petty, “Black Slavery Emancipation Research in the Northern States,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 100 (2012): 293-304.

Nice to know they exist elsewhere, but better to have some of them online! And, for lurkers, Connecticut and Rhode Island also had gradual emancipation laws.