The bills

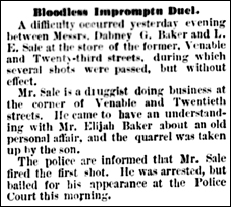

“Bloodless Impromptu Duel” reads the one headline in an early Richmond, Virginia, newspaper:

A difficulty occurred yesterday evening between Messrs. Dabney G. Baker and L. E. Sale at the store of the former …, during which several shots were passed, but without effect.

Mr. Sale is a druggist … He came to have an understanding with Mr. Elijah Baker about an old personal affair, and the quarrel was taken up by the son.

The police are informed that Mr. Sale fired the first shot. He was arrested, but bailed for his appearance at the Police Court this morning.1

The tale was picked up the next day in the “Police Court” column: “Luther E. Sale, charged with unlawfully shooting at Dabney G. Baker. Sent on to the grand jury and bailed.”2

And then, two days later, in the “Hustings Court” column:

The regular quarterly term of this court commenced yesterday. The grand jury … brought in the following report: Jerry Gatewood and John Patterson, on indictments for felony, true bills. The same disposition was made of the following cases of misdemeanor: Luther E. Sale, two cases…3

These, then, offer clues to the story of reader Kimberly’s ancestor, Dabney G. Baker, but they left her with a question: “what is a ‘true bill?’”

These, then, offer clues to the story of reader Kimberly’s ancestor, Dabney G. Baker, but they left her with a question: “what is a ‘true bill?’”

Great question, and the answer starts by understanding what a bill is in the language of the law.

A bill, in law, is a “formal declaration, complaint, or statement of particular things in writing. … A formal written statement of complaint to a court of justice.”4

So, in a criminal case, the formal written set of charges against a person — the complaint — would be a bill.

But when it comes to serious charges here in the United States, and throughout most of the countries with a common law tradition (harking back to the old English law), a prosecutor can’t simply file a charge and force a defendant to come to court and defend himself.

Instead, the prosecutor’s statement of charges has to be considered by a grand jury:

A jury of inquiry, consisting of from twelve to twenty-three men, who are summoned and returned by the sheriff to each session of the criminal courts, and whose duty is to receive complaints and accusations in criminal cases, hear the evidence adduced on the part of the state, and find bills of indictment in cases where they are satisfied a trial ought to be had.5

The right to have a grand jury consider the evidence first, and decide whether there’s enough there to force a person to defend at trial, is so key a part of our legal system that it’s part of the Bill of Rights: “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury…”6

So what the prosecutor did, and does, is present the grand jury with a bill of indictment: “A formal written document accusing a person or persons named of having committed a felony or misdemeanor, lawfully laid before a grand jury for their action upon it.”7

Now, this grand jury review of the evidence was never intended to be simply a rubber stamp. The grand jurors were allowed to, and often did, find that the evidence just wasn’t enough. So the grand jury had two choices. It could find that there was enough evidence to conclude that there was probable cause that (1) a crime had been committed and (2) this defendant was the one who committed it, or it could find that there wasn’t enough evidence of one or both of those facts.

If the grand jury decided there was enough evidence, then it found the prosecutor’s set of charges to be a true bill: “The indorsement made by a grand jury upon a bill of indictment, when they find it sustained by the evidence laid before them, and are satisfied of the truth of the accusation.”8

And if it decided there wasn’t enough evidence, then it found the prosecutor’s set of charges to be a no bill, or not found, or not a true bill, or even in the earliest Latin version, ignoramus:

Formerly the grand jury used to write this word on bills of indictment when, after having heard the evidence, they thought the accusation against the prisoner was groundless, intimating that, though the facts might possibly be true, the truth did not appear to them; but now they usually write in English the words “Not a true bill,” or “Not found,” if that is their verdict; but they are still said to ignore the bill.9

So the Richmond city grand jury, in this case, found there was enough evidence that Luther E. Sale had committed two misdemeanors to approve the formal charges and make him stand trial.

And where, you may ask, is the rest of the story?

In the records of the Richmond Hustings Court, of course. The Hustings Court was the early name of the trial court in Virginia’s independent cities. It served the same function as the county and, later, the circuit courts. These courts were renamed the corporation courts in 185010 and then the city Circuit Courts in 1973.11

And the Library of Virginia has all kinds of holdings of Richmond city court records readily available on microfilm, even for inter-library loan.

Let’s see here… reel 977, the Hustings Court Order Books for 1882-1883. And reel 1007, the convict register for 1870-1896…

Kimberly, you have to let us know what happened to Sale…

SOURCES

- “Bloodless Impromptu Duel,” (Richmond, Va.) Daily Dispatch, 30 June 1883, p. 1, col. 4; digital images, Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ : accessed 27 May 2014). ↩

- Ibid., “Police Court,” Daily Dispatch, 1 July 1883, p. 4, col. 2. ↩

- Ibid., “Hustings Court,” Daily Dispatch, 3 July 1883, p. 1, col. 5. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 132-133, “bill.” ↩

- Ibid., 546, “grand jury.” ↩

- Constitution of the United States, Amendent V. ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 135, “bill of indictment.” ↩

- Ibid., 1191, “true bill.” ↩

- Ibid., 589, “ignoramus.” See also ibid., 827, “no bill,” and 827, “not found.” ↩

- Constitution of 1851, in Francis Newton Thorpe, ed., The Federal and State Constitutions…, 7 vols. (Washington, D.C. : Government Printing Office, 1909), 7: 3829-3852; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 27 May 2014). ↩

- Chapter 544, Virginia Laws of 1973. ↩