Plaintiffs and defendants in error

It’s right there, in the very name of the case.

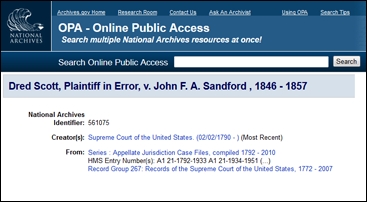

“Dred Scott,” the title of the document begins. “Plaintiff in error.”

It’s the opinion of the United States Supreme Court in one of the most well-known cases in American history.1

It’s the opinion of the United States Supreme Court in one of the most well-known cases in American history.1

Dred Scott, the Missouri slave who sought the assistance of the courts in securing his and his family’s freedom, had won the case at trial in a Missouri state court.

A jury there had agreed that his owner’s actions in taking Scott and his family into free states and territories had freed them from slavery.

But his victory was reversed by the Missouri Supreme Court in 1852. That court overruled years of legal precedents in Missouri and concluded that

On almost three sides the State of Missouri is surrounded by free soil. … Considering the numberless instances in which those living along an extreme frontier would have occasion to occupy their slaves beyond our boundary, how hard would it be if our courts should liberate all the slaves who should thus be employed! How unreasonable to ask it! …

… Times now are not as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then not only individuals, but States, have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequence must be the overthrow and destruction of our government. Under such circumstances it does not behoove the State of Missouri to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit. She is willing to assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery within her limits, nor does she seek to share or divide it with others. Although we may, for our own sakes, regret that the avarice and hard-heartedness of the progenitors of those who are now so sensitive on the subject, ever introduced the institution among us, yet we will not go to them to learn law, morality or religion on the subject.

As to the consequences of slavery, they are much more hurtful to the master than the slave. There is no comparison between the slave of the United States and the cruel, uncivilized negro in Africa. When the condition of our slaves is contrasted with the state of their miserable race in Africa; when their civilization, intelligence and instruction in religious truths are considered, and the means now employed to restore them to the country from which they have been torn, bearing with them the blessings of civilized life, we are almost persuaded that the introduction of slavery amongst us was, in the providences of God, who makes the evil passions of men subservient to his own glory, a means of placing that unhappy race within the pale of civilized nations.2

Scott took his case to the federal courts after his owner, Emerson, died, eventually reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. We all know what happened in that case — how the Court held that African-Americans — enslaved or free — who came or whose ancestors came to America as slaves were not citizens of the United States and did not have what the Court described as “the privilege of suing in a court of the United States.”3 The majority opinion concluded that

they are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.4

In the Missouri trial court, Scott was the plaintiff: the party bringing the case and suing for his freedom.5 But in the Missouri Supreme Court, he was the defendant in error. Why? And how did he become the plaintiff in error when he took his arguments to the United States Supreme Court?

The answer lies in the procedural device that used to be required when somebody lost a case in a lower court and wanted the decision to be reviewed by a higher court. That person had to apply for and be granted what was called a writ of error.

That writ — a written order of the court — was “issued from a court of appellate jurisdiction, directed to the judge or judges of a court of record, requiring them to remit to the appellate court the record of an action before them, in which a final judgment has been entered, in order that examination may be made of certain errors alleged to have been committed, and that the judgment may be reversed, corrected, or affirmed, as the case may require.” 6

In other words, it was the formal way to start an appeal of the trial court order.

How the parties were designated depended on who was applying for the writ. Just as the plaintiff at trial was the person bringing the lawsuit and asking for relief, the plaintiff on the writ of error — called the plaintiff in error7 — was the person bringing the request for the writ and asking for relief on appeal.

So if the person who lost at trial was the defendant in the lawsuit, it would be that trial court defendant who would want the appellate court to reverse what the trial court did. And that trial court defendant would become the appellate court’s plaintiff in error.

The person who won at trial would always be the appellate court’s defendant in error — defending the judgment of the trial court in the appeal. So in our hypothetical here, the trial court plaintiff would be designated as the appellate court’s defendant in error.8

And the designation changed every time the case was taken to a higher court. Here’s how it works:

Case #1:

Plaintiff A wins at trial. Defendant B appeals by filing a writ of error.

As to the writ of error (the appeal) the parties are:

Plaintiff in error: Defendant B (who now is attacking the judgment below by making the appeal)

Defendant in error: Plaintiff A (who now is defending the judgment below)

And the case on appeal will be B, plaintiff in error, v. A, defendant in error.

Case #2:

Defendant B wins at trial. Plaintiff A appeals by filing a writ of error.

Plaintiff in error: Plaintiff A (who is attacking the judgment below)

Defendant in error: Defendant B (who is defending the judgment below)

And the case name on appeal will be A, plaintiff in error, v. B, defendant in error.

This explains how Scott changed his roles in the case:

• He originally brought the lawsuit in the Missouri trial court, so he was the plaintiff there, and he won.

• His owner — the defendant and loser at trial — was the one who wanted the Missouri Supreme Court to reverse what the trial court did, so she was the plaintiff in error to the Missouri Supreme Court — making Scott the defendant in error there, defending the trial court decision.

• Scott became the plaintiff again when he went into the federal court after his owner Emerson died and her brother refused to free him and his family. Scott lost at the federal trial court level, so he was the one who wanted the U.S. Supreme Court to reverse what the federal court ruled. That made him the plaintiff in error to the U.S. Supreme Court and his owner’s brother the defendant in error there.

They’re all parties in error… not the wrong parties.

SOURCES

- Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857). ↩

- Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576, 584-587 (1852). ↩

- Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. at 403. ↩

- Ibid., at 404-405. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 901, “plaintiff.” ↩

- Ibid., 1247, “writ of error.” ↩

- Ibid., 901, “plaintiff in error” (the “party who sues out a writ of error to review a judgment or other proceeding at law”). ↩

- Ibid., 845, “defendant in error” (“the party against whom a writ of error is sued out”). ↩