What exactly is a marriage bond?

Time and again, whenever a marriage bond is referenced, the question comes up.

What happens if the two people named in the marriage bond don’t get married? Isn’t there some kind of court action or record that happens then?

These were the questions asked again this past Saturday at the North Carolina Genealogical Society’s fall seminar, where The Legal Genealogist was privileged to be the presenter in a series of discussions of the law and genealogy.

And underlying these question is an understandable, but mistaken, notion as to just what a marriage bond was.

And underlying these question is an understandable, but mistaken, notion as to just what a marriage bond was.

It seems, doesn’t it, as though a marriage bond should be evidence of an intention to marry — a reflection of an official “engagement.” A man who had proposed to a woman went to the courthouse with a bondsman, and posted a bond indicating his intention to marry the woman.

Right?

Um… not exactly.

I mean, yeah, okay, sure it’s true that you wouldn’t have gone and signed a marriage bond if you didn’t intend to get married, but simply “reflecting an engagement” or “indicating an intention to marry” is about as far from the real purpose of a marriage bond as it’s possible to get.

Remember that, for the longest time, the way folks got married was that marriage banns1 were read from the pulpit or posted at the door of the local church. Usually, banns were read on three consecutive Sundays or posted for three weeks.

For example, in North Carolina, as of 1715, couples had to have “the Banns of Matrimony published Three times by the Clerks at the usual place of celebrating Divine Service.”2 In neighboring Virginia, a 1705 statute required “thrice publication of the banns according as the rubric in the common prayer book prescribes.”3

That notice that two people were going to marry had one purpose and one purpose only: to make sure folks knew there was a wedding in the offing so that they had a chance to come forward and object if there was some legal reason why the marriage couldn’t take place.4 In general, that meant one (or both) of the couple was too young, one (or both) of them was already married, or the law prohibited the marriage because they were too closely related.5

When folks married without banns, however, particularly when they married some distance away from where they were known, there wasn’t the same opportunity in advance to have folks “speak up or forever hold their peace.” The bond then stepped into the breach.

What that bond actually was, then, was a form of guarantee that there wasn’t any legal bar to the marriage. Enforcing the guarantee was a pledge by the groom and a bondsman — usually a relative — to pay a sum of money, usually to the Governor of the State (or colony if earlier, or to the Crown if in Canada6), if and only if it actually turned out that there was some reason the marriage wasn’t legal.

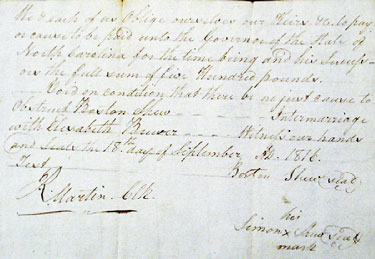

The bond shown here, for example, for the marriage of my fourth great grandparents in Wilkes County, North Carolina, in 1816, was a promise by the groom Boston Shew and his brother Simon to pay the Governor of North Carolina five hundred pounds, but it provided that it was “Void on condition that there be no just cause to Obstruct Boston Shew — Intermarriage with Elizabeth Brewer.”7

The use of marriage bonds was common, particularly in southern and mid-Atlantic states, well into the 19th century,8 when most jurisdictions started relying on what the couple said in a written application for a marriage license.

And the laws about those… well… we’ll get to those some other day…

SOURCES

Note: Information in this post was originally included in a January 2012 blog post, The ties that bond.

- “Public announcement especially in church of a proposed marriage; plural of bann, from Middle English bane, ban proclamation, ban.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.merriam-webster.com : accessed 16 Nov 2014.) ↩

- North Carolina Laws of 1715, chapter 8, in William Saunders, compiler, Colonial Records of North Carolina, Vol. 2 (Raleigh, N.C. : P.M. Hale, State Printer, 1886), 212-213; online version, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South (http://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/), University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. ↩

- Virginia Laws of 1705, chapter XLVIII, in William Waller Hening, compiler, Hening’s Statutes at Law, Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the first session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: Thomas DeSilver, printer, 1823), 441; digital images, HathiTrust Digital Library (http://www.hathitrust.org/ : accessed 16 Nov 2014). ↩

- See generally Susan Scouras, “Early Marriage Laws in Virginia/West Virginia,” West Virginia Archives & History News, vol. 5, no. 4 (June 2004), 1-3. ↩

- Maryland by statute required marriages to follow the Church of England Table of Marriages, drawn up in 1560, that said when relatives were too closely related. Chapter 12, Laws of 1694; Maryland State Archives, Acts of the General Assembly Hitherto Unprinted 1694-1698, 1711-1729, vol. 38: 1; Archives of Maryland Online (http://msa.maryland.gov/ : accessed 16 Nov 2014). For that table, see F. M. Lancaster, “Forbidden Marriage Laws of the United Kingdom,” Genetic and Quantitative Aspects of Genealogy (http://www.genetic-genealogy.co.uk : accessed 16 Nov 2014.) ↩

- See “Marriage Bonds, 1779-1858 – Upper & Lower Canada,” Library and Archives Canada (http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/ : accessed 16 Nov 2014). ↩

- Wilkes County, North Carolina, Marriage Bond, 1816, Boston Shew to Elizabeth Brewer; North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh. ↩

- FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/), “United States Marriage Records,” rev. 18 July 2014. ↩

It is indeed true that taking out a marriage bond did not necessarily mean that the marriage actually took place. I have such instance in North Carolina. However, what I have never seen (yet) is any case where a bond was actually forfeited. Have you?

I haven’t seen a forfeited marriage bond, Craig. Lots of other types of bonds forfeited, but not a marriage bond.

Your reference to the

can be a really important point.

Here is an example:

The Haywood County, North Carolina marriage bond for Milton Brown’s marriage to “Kizeah Hooper Daughter of Absolom Hooper” got written without any date on it. But there is a great clue to the timing because the groom and his bondsman pledged that

“…we Milton Brown &

Holoman Battle are dually & severally held

firmly bound unto Jesse Franklin Esq. & Governor”

Governor Franklin served only one term, in 1820 and 1821, before he retired; the eldest son of Milton Brown was born perhaps in October 1819 or else in 1820. Thus, it is probable that the wedding for the couple happened during 1820-1821.

Good point and good example.

I have an unusual situation. A Garrard Co KY court order dated Sep 1809 recorded that “Jacob & Elizabeth, inf orphans of Philip Bellis, chose Adam McCormack as guardian, & Adam appointed guardian for Polly Bellis.” Polly was presumably under the age of 14 otherwise she also would have “chosen” Adam as her guardian. Other researches have estimated that Mary (Polly) was born about 1799 but no documentation exists.

Several years later, Mary (Polly) had moved to Bourbon Co, KY and court records there reflect: “MARRIAGE BOND: HALL, James and Polly BELLIS of BC. Bond Date: 17 March 1817. Bondsman: Adam McCORMACK. Marriage Date: 17 March 1817.”

Then, in May 1817, Nicholas Co (adjacent to Bourbon Co) court recorded this: “Mary Hall, late Mary Bellis came into court and being admitted by the court made choice of James Hall for her guardian and thereupon the said James Hall entered into and acknowledged Bond agreeable to law.”

I don’t quite understand, if she was already married to James, why Mary (Polly) had to choose him as her guardian a few months later? The only thing I can come up with is that James Hall was under 18 at the time of the March 1817 wedding; if that’s the case, he didn’t have a bondsman unless Adam McCormick served as bondsman for both. Other researchers have James born in 1797 but I have no proof of that. So if my guess is right and he only turned legal age after the marriage, I’m still wondering why he didn’t automatically become Polly’s “guardian” since he was her husband. P.S. Adam McCormick was Polly’s brother-in-law.

The answer will most likely be found in the reason the guardianship was created: what did James have to do on Polly’s behalf in Nicholas County? The law probably required a guardian for that purpose.

Thank you Judy. I just assumed that a husband was de facto the guardian of his wife.

So I need to check the actual marriage records for a husband and wife who married in 1880, when BOTH were remarried by 1895. (with at least one burned county where no divorce papers would survive ) And all lived all their lives in NC, as far as I can tell.

Burned counties are soooooooo frustrating!

Judy, what would it mean if there was a marriage bond/license with no bride’s name filled in? I have one of those from Surry County, North Carolina, in 1830. It reads as a bond (but says license), promising 500 pounds to the NC governor John Owen, “but to be void on condition that there is no lawful cause to obstruct a marriage between” groom’s name “and” bride’s name blank. What am I to think about this??

It would seem to me it would mean, more than anything else, that some clerk didn’t do his job!

Ha! Either that, or the groom wasn’t sure who he was going to marry!

And, of course, the clerk was asleep on the job for what I think may have been MY ancestor’s bond!

Judy,

If a brother is listed as the guardian on a note to authorize a marriage license for a younger sister can we assume that her mother is deceased? We know her father is deceased but can not find a trace of her mother. In other works would her mother have been able to sign for the marriage bond/license or do we assume she is deceased. Thank you!!

Unfortunately, no assumptions can be made here. You’d need to look at the law at the time and consider the possibility that the brother was appointed legal guardian even though the mother was living.

Why is it never easy?? Thank you will try to find where that information may be.

If it was easy, it wouldn’t be so much fun! What jurisdiction and what time frame?

It was in Kentucky, Mercer Co. 1902

I do hope you’ll get to licenses for sure someday. I’ve done some research to create this guide, but now I’m trying to go more in-depth perhaps for an article of some sort. It’s just been that fascinating!

Is there any way of knowing the relationship between the bride/groom and the bondsman?

Only by doing the paper-trail research to be sure. It’s usually kin, but which kind? That’s always up for grabs.

On my grandmother and grandfathers Kentucky marriage bond from 1900 her mothers birthplace list DO. What does this mean?

DO is usually short for ditto — same as whatever is above most likely.