The language of the law. Part Latin, part Anglo-Saxon, all confusing.

So The Legal Genealogist had an absolute ball doing that webinar Tuesday for the Friends of the National Archives-Southeast Region on patents, and almost immediately had a question by email.

“Patents for inventors?” the reader asked. “I thought patents were issued for land.”

Now I thought briefly about being a little snarky… because I did answer that question in the webinar. But I do realize not everyone can be online in the middle of a workday afternoon, and it really is annoying that one seemingly simple six-letter word could be used in two such seemingly different ways.

Truth is, the uses aren’t really all that different.

Here’s the deal.

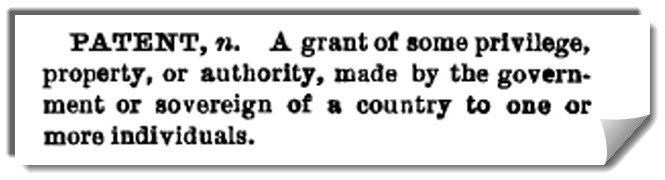

A patent, by definition, is a “grant of some privilege, property, or authority, made by the government or sovereign of a country to one or more individuals.”1

Now think about that for a minute.

I’m the King.2 I own all the land in this province or colony or territory. And I give you some. Or sell it to you. Or let you have it in return for military service or some other good deed.

What I’ve just accomplished is a “grant of some … property,… made by the … sovereign of a country to one or more individuals,” right?

In other words, a patent.

That’s why a lot of land transfers, from the royal governments in colonial days (whether Dutch, French, Spanish or English), and from the federal or state governments after the United States became a country, were accomplished by means of patents.

But now let’s change the facts a little. Say I’m the federal government.3 And I give Eli Whitney the singular right to build, use and sell his cotton gin invention for a period of 14 years.4

What have I just accomplished there?

I’ve just accomplished a “grant of some privilege, … or authority, made by the government … of a country to one or more individuals.”

In other words, a patent.

And that’s why one word is used for both concepts: a patent for land; a patent for inventions.

Patently clear? Maybe.

Patently ridiculous, maybe too, but hey… nobody ever said the language of the law had to make sense.

SOURCES

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 877, “patent.” ↩

- Okay, okay, so I’m the Queen. Whatever. ↩

- An appalling thought, given the state of affairs in Washington these days. But hey… stay with me, okay? It’s just a hypothetical. ↩

- Eli Whitney, patent no. 72X (1794); Records of the Patent Office (Reconstructed Records) relating to “Name And Date” Patents, 1837-87; Records of the Patent and Trademark Office; Record Group 241, National Archives II, College Park, Md. ↩

I discover that a patent is in origin “letters patent” that is an open document for all to read, with a seal attached. In contrast the King would also have “letters close” which would be sealed in such a way that the seal had to be broken to read the letter. So “letters close” were really private letters which would give evidence that someone had opened and read them.

Delighted that my schoolboy Latin resurfaces! Verb patere – to be open. The adjective patent has – in the way that English does to words – morphed into a noun, with patents for inventions and land and all sorts!

Love it! Thanks, Graham!