The maybe-the-clue-is-there document

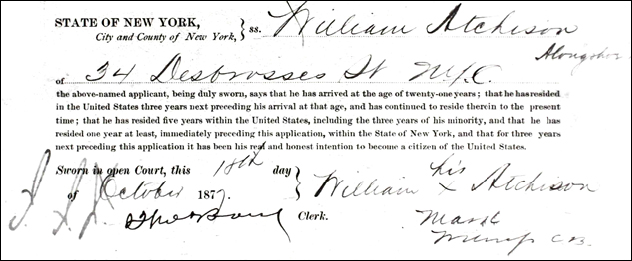

Reader Jane Mackesy was delighted to locate the 1877 naturalization petition of one William Atchison, a man she thinks could be her second great grandfather, and language in the petition gave her hope that she might be able to narrow down how old this William was and when he came to America.

But on careful review, she found that the language was a little confusing. She wrote:

It says that “he has arrived at the age of twenty-one years; that he has resided in the United States three years next preceding his arrival at that age, and has continued to reside therein to the present; that he has resided five years within the United States, including the three years of his minority, and that he has resided one year at least, immediately preceding this application, within the State of New York, and that for three years next preceding this application it has been his real and honest intention to become a citizen of the United States.”

So, she asked, “how long before 1877 did he arrive? I’m confused by the three year/five year info and the ‘including the three years of his minority’??? If he arrived at 21 was he still a minor?”

Uh oh.

You know what this is, right?

This is what’s called a minority naturalization or “one paper” naturalization, under the Act of May 26, 1824.1 Until it was repealed in 1906,2 it provided an easier path to citizenship for people brought to America as children.

Adults who arrived during that same time frame had to file a declaration of intention to become a citizen and then wait two years before they could file their petition for naturalization.3 But a minor could sit back until he turned 21 and then file one single form and be naturalized without the two-year wait.

The thinking was that someone who’d already been in America for years had waited long enough to become a citizen just by being forced to wait until he turned 21. He shouldn’t have to wait until he turned 21 — legal age to act in such an important matter — to file his declaration of intent and then wait another two years, until age 23, to be naturalized.

Now the law contained a lot of requirements, and — if the person was complying with the law — here’s what would have to be true of the person applying for naturalization under this “one paper” system:

a. The person arrived in the US before he turned 21.

b. The person was at least 21 years old at the time he applied for naturalization.

c. The person lived in the US at least three years before turning 21.

d. The person lived in the US at least five years before applying for naturalization (which could be all before age 21 or could be a combination of no fewer than three years before and two years after age 21).

e. The person lived in the state where he was naturalizing for at least a year before applying for naturalization.

With all those requirements, you’d think that one of these “one paper” naturalizations would be a wonderful source of clues to the person’s age, and arrival date in America.

And to some degree that’s true. Let’s think about our William Atchison here.

The document says he was naturalized in October 1877 in New York City’s Superior Court.4 So we can reasonably conclude that he could not have been born later than 17 October 1856 in order to have been age 21 on 18 October 1877.

The problem is… the law didn’t put an end date to the time when someone who came to America as a minor had to petition for naturalization under this “one paper” system. In other words, the statute essentially provides for a sliding scale. True, he couldn’t have been born later than 17 October 1856. But he could have been born any time before that date in 1856. He could have been 21 years old in 1877 — or 91 years old — and the statute didn’t care.

The residence provisions weren’t any better. They simply provided that he had to have lived in America at least five years, and at least three of those years had to be before he turned 21. So you could have that born-in-1856 immigrant being qualified for naturalization if he arrived in America in 1872. That would give him five years of residence in America including the required three years before he turned 21. But he could also have arrived in any year between 1856 and 1872. That would still give him the required five years in America and three years before age 21.

And if he was older than 21 years? He could have arrived, under the law, at any time before he reached age 18. Our hypothetical 91-year-old in 1877 (so born in 1786) could naturalize under this statute as long as he arrived not later than 1804. Someone born in 1840 could have come to America in 1850 and not naturalized until 1877. That would have qualified too.

So the minor naturalization system doesn’t give us the information we’d like to have to narrow down how old this William Atchison was or when he arrived in America — even assuming he was complying with the law.

And that raises a second problem.

It’s the problem of fraud.

You see, particularly in a big city where the court personnel wouldn’t have any way of knowing the facts about an applicant, there wasn’t any way to police this system. And the reality is that, as long as he could round up a witness to go to court with him, an immigrant could walk in, swear he’d been there since childhood, and naturalize — even though he’d just gotten off the boat the day before. This potential for fraud — and documented abuses of the system — were the big reasons why the one paper naturalization was eliminated in the 1906 statute.5

So these “one paper” naturalizations can leave us feeling pretty clueless.

And, as usual, it’s only by combining them with all the other bits and pieces of a paper trail that we may be able to nail our immigrant’s feet to the dock of an arrival port.

This one document isn’t going to do it by itself.

SOURCES

- §1, “An Act in further addition to ‘An act to establish an uniform rule of Naturalization, and to repeal the acts heretofore passed on that subject,’” 4 Stat. 69 (26 May 1824). ↩

- “An act to establish a Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, and to provide for a uniform rule for the naturalization of aliens throughout the United States,” 34 Stat. 596 (29 June 1906). ↩

- §4, “An Act in further addition to ‘An act to establish an uniform rule of Naturalization, and to repeal the acts heretofore passed on that subject,’” 4 Stat. 69 (26 May 1824). ↩

- Naturalization petition, William Atchison, 18 October 1877; New York County, New York, Superior Court Bundle 285, Record No. 243A; digital image provided by reader Jane Mackesy. ↩

- See FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/learn/wiki/), “United States Naturalization and Citizenship,” rev. 27 Sep 2014. ↩

An expert in Irish genealogy warned me about the fraud issue years ago. He said you always needed to take residency testimony with way more than a grain of salt when it came to the Irish because, unlike immigrants from other countries who usually needed that five year residency period in order to learn English, the Irish were usually already fluent in English before they arrived in the USA. They also saw absolutely nothing wrong with telling a wee fib in order to speed up the accomplishment of a worthy objective with a minimum of fuss. No harm, no foul.

The Irish certainly weren’t the only ones!