Why not the mother?

Reader Jeanie Attenhofer was struggling to understand what happened when her third great grandfather died in 1828.

He was killed, she said, along the Santa Fe trail — shot with his own gun (“he fell asleep at the switch, as it were,” she reports) — and left a wife and four minor children.

And that’s when something happened that she couldn’t figure out. The children were placed under the guardianship of their mother’s brother. “But why?” she asked. “Why would her brother have been given guardianship of the children if she was still alive?”

And that’s when something happened that she couldn’t figure out. The children were placed under the guardianship of their mother’s brother. “But why?” she asked. “Why would her brother have been given guardianship of the children if she was still alive?”

The Legal Genealogist understands Jeanie’s confusion here. We are, after all, 21st century women accustomed to taking care of ourselves and our families. But that wasn’t always the expectation in the past — and it certainly wasn’t what the law expected.

The first thing to keep in mind here is that the law generally didn’t get involved with children at all in generations past — not the way it does today and not with our modern focus on the best interests of the child.

About the only time the legal system really cared about kids until very modern times was when they were a public nuisance or a public charge, in which case they were locked up or bound out, or when they were entitled to get property, in which case the law stepped in to make sure the kids didn’t trade the property for a hunting dog and no adult stole it from them.

And when the law stepped in, in the vast majority of cases, it stepped in to give control to a man.

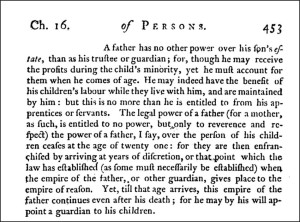

We start with the fact that, at common law, control over the persons and the estates (property) of a child rested with the father — and only the father. And in the course of explaining the legal power of the father, Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws of England noted, in passing, that “a mother … is entitled to no power, but only to reverence and respect…”1

Let’s repeat that: “a mother … is entitled to no power, but only to reverence and respect…”

We can add in the legal disabilities of women generally, both in the common law and in early statutes. Think, just as one example, about the fact that a wife didn’t ordinarily inherit from her husband: all the property went, not to her, but to the children — and then often to the sons and not the daughters.2

So when it came to guardianship, the law naturally looked to men as well — at least when it came to property.

To understand that better, we need to keep in mind that, in the common law, there were three essential types of guardians: the guardian by nature; the guardian for nurture; and the guardian in socage. The guardian by nature or guardian for nurture had the right to physical custody of a minor child. That was always the father or, if the father died without naming a guardian in his will, then the mother.3 The difference between the two was that the guardianship by nature lasted to age 21 and gave the guardian control over the child’s personal property. Guardianship for nurture lasted to age 14 and didn’t involve property at all.4 The guardian in socage was the one who had custody of a minor’s lands and person.5

In America, the guardian in socage gave way to the guardian by statute — the person “appointed for a child by the deed or last will of the father, and who has the custody both of his person and estate until the attainment of full age.”6 And if nobody was named by the father, the court stepped in with a guardian by appointment of the court, with the same authority.7

Notice that this type of guardianship came into play only when there was an estate involved. If Papa died, and there wasn’t any property involved, then if Mama was able to keep the kids, she simply kept them. If Mama died too, then Gramma or Grampa took them in. Or Aunt Fanny and Uncle Bert. Or a cousin down the road. Or even a neighbor down the road. This was informal, and if the kids got raised, didn’t starve and didn’t run wild, nobody took a second look. Remember: the notion of formal adoption under the law didn’t even start in the United States until the 1850s.8

But when property was involved, the preference was overwhelmingly for the nearest male relative who couldn’t inherit from the child to serve as guardian. Even the example used by Blackstone points this out: “where the estate descended from his father, … his uncle by the mother’s side cannot possibly inherit this estate, and therefore shall be the guardian.”9

And that’s exactly what happened in Jeanie’s case: the mother was bypassed by the law as entitled to “reverence and respect” but not to legal power, and her brother was named the guardian instead.

That doesn’t mean the children lived with him. In all likelihood, they would have remained with their mother. But the legal authority over their property remained with him (or any substitute guardian) until each child reached full age.

SOURCES

- William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book I: The Right of Persons (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1770), 453; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 1 March 2015). ↩

- See e.g. ibid., at 463-464. ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 552-553, “guardian by nature.” Ibid., 553, “guardian for nuture.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid., 553, “guardian in socage.” ↩

- Ibid., “guardian by statute.” ↩

- Ibid., 552, “guardian by appointment of the court.” ↩

- See “Timeline,” The Adoption History Project (http://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/index.html : accessed 1 Mar 2015). ↩

- Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book I: The Right of Persons, at 461. ↩

I’m so glad that I read something in passing about this legal history before I got back to one branch of my family. I have a brick wall on my maternal side right now because I realized that between the guardianship laws and the marriage bond laws at the time, there’s a big warning sign that the wife named in a will of the father of my last female on the line isn’t her mother. She does appear to be the mother of the younger siblings, but not of my ancestor. And that’s why I’m on the look out for those carrying the mtDNA of this later wife to test unless I can find the right marriage records to prove my case.

Good for you for recognizing this, Christie!

Glad to see this example. I’ve been reading up a little on this very issue because of some relationships I’m trying to figure out. The one thing you don’t mention–separate from guardianship, but potentially a helpful source of information–is dower-right, the right of a wife to 1/3 of the family property. It’s dower-right, or lack thereof, that I think is telling me that a wife must have predeceased her husband in the case I’m dealing with.

I’ve talked about dower a lot in other contexts, Pat — do a search for the word “dower” and you’ll come up with a lot of examples. But remember that you need to focus on (a) the time frame (when was dower abolished in the jurisdiction you’re dealing with) and (b) the place (some jurisdictions never had dower, like some of those that followed the French or Spanish civil code). Dower was only a life estate, by the way, not the right to property but the right to live on and profit from the property during her life. She didn’t own the land itself, couldn’t will it or sell it.

My great grandmother was named executrix of her first husband’s will along with her brother. The brother had her removed as executrix when she remarried (my great grandfather) so he could sell the farm, in Clark Township, New Jersey, where she was living with her new husband (and my newly born grandmother). The proceeds of the sale were to be used to pay a mortgage if I remember correctly. The purchaser of the land filed suit over whether the brother had the right to sell the land himself, without the widow. The case made it all the way to the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1881 and it was determined that the brother did have the right to sell. [New Jersey Supreme Court (1882). New Jersey Law Reports. Soney & Sage.; Weimar v. Fath, pp. 1-13. (https://books.google.com/books?id=IXc0AQAAMAAJ)]

Despite your general case, so well explained, there were times when the widowed mother was appointed guardian to a child. I have seen this in Washington Co., MD ca. 1814 and in Sussex Co., DE in 1784 (where the child was an infant born posthumously). But usually not if she remarried, since courts recognized the potential for the new husband to fritter away the child’s property. Still, one of my ancestors remarried and her husband acted in Sussex County, DE Orphans Court as estate administrator and on behalf of the minor children (such as seeking permission to sell some of the deceased father’s land to pay for upkeep/schooling). No one was officially designated “guardian” in that case (1760s).

There are always exceptions and exceptional circumstances.

Yes, there were exceptions, and one common one was where an older child chose his or her mother; the court would generally appoint her as guardian for the others as well.

I love the treasures where the Court noted that the child was not only over age 14 (or whatever the statutory age of choice was), but had (say) turned age 15 on 20th of March last past. To think that so many do not pursue estate and guardianship records 😉

ANY kind of court record is likely to have those gems… but that one makes you want to kiss the clerk.

You shouldn’t assume that when there is no dower provision in the husband’s will that the wife has predeceased him, as other provisions may have been made. In one of my families, the wife was taken out of the will leading to the presumption, by previous researchers, that the wife had died. I found her four years later in the 1820 census in the same neighborhood as head of household with, presumably, her four minor children! Not the only problem with previous research on this family, either.

Mike, dower was rarely mentioned in a husband’s will since dower operated as a matter of law, no matter what the husband wrote into his will. The widow almost always had the right to dower, sometimes at the price of giving up anything she was left in the will, but always notwithstanding the will if she chose.

Amen to this. One of my clients and the local DAR registrar are in (as far as I know) unresolved disagreement over this very issue. The husband did not name his wife in his will, and therefore according to the DAR she was dead. Not so fast! All of the land and nearly all of the personal property had been left to her by her father in a life estate, and upon her death then to her heirs. She is on the land tax lists until 1787, when her land is then taxed to, appropriately, her surviving children. It’s a long story. The husband attempted to devise his wife’s land in his will, but that is not what happened. He no right to after his death. Don’t you love these sorts of knotty issues?

This is useful. My 5th great-grandmother was widowed while her two sons were quite young. She was appointed administrator of the estate by court, and guardian of the children. I understood this was unusual, but didn’t realize how unusual it was. In addition, there was considerable property involved, which appears to have come from her side of the family, or at least through them. She managed the property, and never remarried, though she lived some decades longer. I am presuming she stayed unmarried in order to retain and protect the property for her children and to ensure it stayed within the family. The two sons in adulthood lived in the area, one on one parcel, the other nearby. I do not yet know if the parcels they lived on had been part of the estate, nor if she lived with them or with another family member. Among my “to-do’s” for this family is a thorough search for land and court records to see if I can gain any further insight into this unusual situation.

Her appointment as administrator is not all that unusual, Annie: many states had a statutory preference for the widow. But it isn’t ordinary that she would have been guardian. Good for her! Track down those records — should be quite a story there.

My 4th-great-grandmother was widowed with young children in 1828 and also remained a widow the rest of her life. While of course we can’t know for sure what the reason was in either of our cases, personally I always figured it was most likely because her husband had left her with a farm and enough money to live on, and so she had no financial incentive to remarry and got to have a lot more rights as a widow than she would have had as a (re)married woman.

P.S. Judy, you would be pleased that a document in a probate file was what proved her parentage.

Good for you, Liz! (And yes, probate records are wonderful!)

The DAR and I have gone ’round and ’round about my third great-grandfather and proof it was his brother, father and brother-in-law who posted bond on the estate and the brother and brother-in-law became guardians of the four minor children. Because the father, brother and brother-in-law were not named as such in the court records, then the relationship could not possibly be what is presume it to be! The mother was still living but it wasn’t until several years later she became guardians of the minor children. I argued the court wouldn’t give guardianship to somebody down the road and especially when the presumed father and uncle had the same surname! So far, I’ve lost the argument because there’s “no paper trail” but I haven’t given up.

Every group has its own standards … and some make more sense than others.