150 years ago today

Let us all stop at some point in our busy lives today for a moment of silence.

Today, 3 April 2015, marks the 150th anniversary of the fall of Richmond.

The account of the hours from the time Jefferson Davis ordered the evacuation of the Confederate government from the City of Richmond on the morning of Sunday, 2 April 1865, to the moment in the early morning hours of Monday, 3 April 1865, when the Union troops entered the city, is chilling:

By early spring 1865 the citizens of Richmond had become used to the threat of capture by the Federal army whose soldiers the Richmond newspapers described with great imagination as the vilest of humanity. Richmond had endured some frighteningly close chances, and its inhabitants had grown accustomed to the sound of artillery fire from just ten miles outside the city. Their faith in Robert E. Lee was so complete that they knew beyond the shadow of a doubt that he would never allow Richmond to be taken. …

Lee had always felt constrained by the duty to defend the Confederate capital. But abandoning it, he knew he could move more freely. So when General Philip Sheridan’s troops overran Confederate defenses at Five Forks on Saturday April 1, Lee made the decision to abandon the Petersburg defenses and, in doing so, to abandon Richmond.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis had discussed the probability of quitting Richmond with Lee a month earlier, and he had already sent his wife and family out of the city. Despite these precautions, Davis still believed Lee could stave off disaster.

I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight.

–General Lee’s telegram to President Jefferson Davis

Davis read General Lee’s telegram while attending Sunday morning church service. He immediately issued the first orders for the Confederate government’s evacuation. Word spread across the city. Lawley reports, “…quickly from mouth to mouth flew the sad tidings that in a few hours Richmond’s long and gallant resistance would be over.” Officially, the citizens of Richmond did not hear anything for hours, but they could not help but notice the fires in front of the government offices as official documents burned. …

All through the night preparations for fleeing from the city kept the Richmonders busy. When the last Confederate soldiers rode across the pontoon bridge to catch up with Lee’s troops, those left behind believed they would return soon, to take the city back from the Yankees. In the city small fires of documents still burned. …

… The fires, though, grew out of control, burning the center of the city …

Embers from the street fires of official papers and from the paper torches used by vandals drifted. The wind picked up. Another building caught fire. The business district caught fire. …

The Union cavalry entered town. … Union General Godfrey Weitzel … ordered his troops to put out the fire. The city’s two fire engines worked, bucket brigades were formed. Threatened buildings were pulled down to create firebreaks. Five hours later the wind finally shifted, and they began to bring it under control. All or part of at least 54 blocks were destroyed, according to Furgurson. Weitzel wrote “The rebel capitol, fired by men placed in it to defend it, was saved from total destruction by soldiers of the United States, who had taken possession.” And the city rested.1

Now The Legal Genealogist is way too much of a Yankee to be mourning the impending end of the Confederacy that the fall of Richmond foretold. My Texas-born-and-bred grandfather referred to this Colorado-born grandchild as a “damnyankee” — one word, of course — for my north-of-the-Mason-Dixon-line attitudes.

It’s just that I am too much of a genealogist — and way too much of a descendant of Virginians — not to be mourning what we lost in those fire.

The loss of all those records.

You see, so many Virginia counties believed their courthouses would be burned by the Yankees as battle after battle was fought on the soil of the Old Dominion. So to preserve and protect the records so near and dear to our genealogical hearts — deed books, will books, court minutes, vital records and more, the counties carefully boxed them up and sent them — for safekeeping — to the city they were sure would never fall.

They sent them to Richmond.2

Where, during that terrible 24 hours before the city officially fell to the Yankees, the Confederate Government set some records on fire — and the spread of the fire took out the rest.

Records loss from the Richmond fire is simply staggering, among them some or all of the records of:

• Elizabeth City County

• Gloucester County

• Henrico County

• Hanover County

• James City County

• Mathews County

• New Kent County

• Richmond City

• Warwick County3

So let’s have a moment of silence today for the fall of the City of Richmond.

And the catastrophic loss of colonial and early statehood records that terrible time, 150 years ago today.

SOURCES

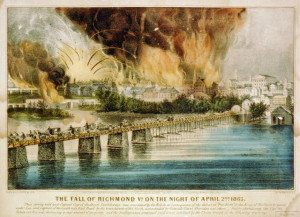

Image: “The fall of Richmond Va. on the night of April 2nd” (New York: Currier & Ives, c1865); Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov : accessed 2 Apr 2015).

- “The Fall of Richmond, Virginia,” Civil War Trust (http://www.civilwar.org/ : accessed 2 April 2015) (emphasis added). ↩

- Carol McGinnis, Virginia Genealogy: Sources and Resources (Baltimore, Md. : Genealogical Publ. Co., 1993), 155. ↩

- “Lost Records Localities: Counties and Cities with Missing Records,” Library of Virginia (https://www.lva.virginia.gov : accessed 2 Apr 2015). ↩