Continental level information

We all know by now … or we should know by now … that the admixture percentages reported by the genealogy DNA testing companies are really rather awful at the level where we really want the information: the country level.

The simple fact is, no test today can accurately tell us that we are, say, 46% German, 22% Irish, 20% English and 12% Italian. The similarities among the European populations are just too great to allow for that degree of specificity — at least not if we want to be sure about it.1

The simple fact is, no test today can accurately tell us that we are, say, 46% German, 22% Irish, 20% English and 12% Italian. The similarities among the European populations are just too great to allow for that degree of specificity — at least not if we want to be sure about it.1

But what about at a broader level? At the continental level? Can DNA testing give us accurate information about our ancestral origins as between, say, European and African and Asian?

Reader Shirl poses this question in her own family: “I have reason to believe that my maternal ancestry includes an African-American who started passing as white in the late 1700’s in New England; the documented ancestry is all British Isles and German. Would an autosomal DNA test be able to determine if this is true?”

And the answer is:

(Drum roll, please…)

It depends.

Yes, European and African and Asian DNA shows very distinct patterns. At the continental level, autosomal DNA can tell us a lot about our deep ancestry.

But here’s the rub when we try to use it.

Each of us inherits 50% of our autosomal DNA from the father and 50% from the mother. So the odds of showing our ancestral origins if either parent was 100% European or 100% Asian or 100% African are essentially 100%: the child’s autosomal DNA should show roughly 50% of each parent’s ancestral origins.

But let’s say each parent was a 50-50 mix: one parent was 50% European and 50% African, and the other was 50% European and 50% Asian. On average, each child of this couple would end up showing roughly 50% European, 25% African and 25% Asian. Still a high percentage, still clearly detectable.

But now watch the average percentages inherited as we go down the generations:

From a parent: 50%

From a grandparent: 25%

From a great grandparent: 12.5%

From a second great grandparent: 6.25%

From a third great grandparent: 3.125%

From a fourth great grandparent: 1.5625%

From a fifth great grandparent: 0.78125%

From a sixth great grandparent: 0.390625%

From a seventh great grandparent: 0.1953125%2

Remember: these are averages, not set-in-stone numbers. Autosomal DNA changes — a lot! — with each and every generation because of a process called recombination. That’s a process where all of the pieces of autosomal DNA we inherited from our parents — what’s in each pair of chromosomes we have — gets mixed and jumbled before half (and only half) of those pieces gets passed on to the next generation. Because of this jumbling, the range of DNA we might inherit is pretty broad — it could be higher or lower than the average percentage shown.3

Now if we figure an average of 25 years per generation, for someone who is — say — 50 years old today, here’s how this translates into time frames:

Born around 1940: 50%

Born around 1915: 25%

Born around 1890: 12.5%

Born around 1865: 6.25

Born around 1840: 3.125

Born around 1815: 1.5625

Born around 1790: 0.78125

Born around 1765: 0.390625

Born around 1740: 0.1953125

If Shirl’s ancestor was already passing for white in the late 1700s, we’re probably talking about a racial mix in the sixth or seventh great grandparent generation: the first generation where African and European ancestry came together.

In other words, if the family story is true, Shirl’s African ancestry is likely to represent not more than about 0.2% of her autosomal DNA. Again, some people will have a higher percentage from an ancestor that far back, and some will have a lower percentage, in both cases by pure random chance. It’s a matter of whether or not Shirl won the genetic lottery and actually had that African DNA passed on to her.

Now if Shirl did win the genetic lottery, she could have that 0.2%. So… is 0.2% detectable?

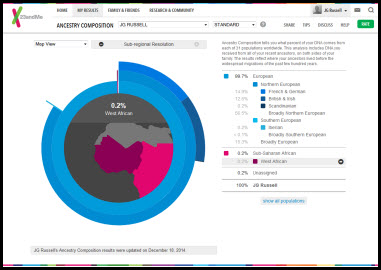

It can be. At 23andMe, for example, my own results show 0.2% sub-Saharan African at both the standard and the speculative levels of confidence. Once I go to the conservative confidence level (a level where the scientists think they’re 90% sure4), however, my African ancestry fades into the background.

And not every company reads our DNA the same way. At AncestryDNA, my results still indicate less than one percent African, but there it’s shown as Africa North, rather than sub-Saharan Africa. And at Family Tree DNA, my results don’t show African at all; they show some from Asia Minor instead.

So do I have African ancestry in a generation born around 1740 or so? Maybe. Maybe not. And maybe, because of random chance, it could be from much farther back — so far back that it really does fade into the background.5

That’s our first problem: if we do find detectable African DNA, it won’t tell us, by itself, how far back in time the DNA comes from. It can give us some hints, pointing us to a general time frame where we can start looking at the paper trail, but by itself it can’t prove when our African ancestor lived.

And there’s another problem: autosomal DNA can’t disprove any particular ancestral origin when we’re dealing with those very small percentages. Shirl may very well have African-American ancestry back in the late 1700s but, by that random force of recombination, may just not have inherited the DNA that could show it. The ancestor is still in Shirl’s family tree, but may not have made it into her genetic family tree.6

So it’s worth doing autosomal testing to look for this small an amount of possible African ancestry. What’s critical is understanding that finding it won’t tell us how far back in time it came from, and not finding it doesn’t prove we don’t have African ancestry.

SOURCES

- See generally Judy G. Russell, “Admixture: not soup yet,” The Legal Genealogist, posted 18 May 2014 (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : accessed 11 July 2015). Also, ibid., “Making the best of what’s not so good,” posted 22 Feb 2015. ↩

- See generally ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Autosomal DNA statistics,” rev. 4 July 2015. ↩

- See ISOGG Wiki (http://www.isogg.org/wiki), “Recombination,” rev. 14 June 2015. ↩

- See 23andMe Customer Care, “Confidence thresholds in Ancestry Composition,” 23andMe (https://www.23andme.com/ : accessed 11 July 2015). ↩

- See generally Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Kasia Bryc, “How Long Ago Did African Ancestry Enter My Family Tree?,” The Root, posted 10 July 2015 (http://www.theroot.com/ : accessed 11 July 2015). ↩

- See Blaine Bettinger, “Q&A: Everyone Has Two Family Trees – A Genealogical Tree and a Genetic Tree,” The Genetic Genealogist, posted 10 Nov 2009 (http://www.thegeneticgenealogist.com/ : accessed 11 July 2015). ↩

I think that all of the genealogy-related DNA testing companies have to develop their own proprietary models, which compounds the issue of interpreting results. True? Then the DNA data in question when applied to company A’s model may be identified as originating in one region of the world, and when matched to company B’s model it’s a nearby region. I’m not surprised – and in fact welcome it – when companies rerun their models to reflect the richer datasets they are accumulating. My %’s change somewhat, and I believe that the results are getting just a little bit better each time.

Yes, each company has its own dataset that affects its analysis. I wish I could agree that the results are getting better; my problem is that as long as the datasets compare living people to living people, I fear there will always be an inherent error factor that renders the results less than useful. My friend Blaine Bettinger suggests that real improvements may result when we factor in ancient DNA, from the oldest bone samples we find and analyze.

So, it doesn’t disprove it. But does is prove it? In one set of three oldest generation siblings, two showed zero African, but one showed 1% or <1%. Does that prove there was African ancestry? Or could it just be noise? (Same scenario for another group of three where one showed 1% European Jewish.) Thanks.

The Gates-Bryc article referenced in footnote 5 probably gives you your best answer.

Hi Judy,

Thank you for the prompt and thorough reply. I am, by profession, a molecular evolutionary biologist, so I well understand the generational DNA dilution effects, hence my question as to whether the current state of autosomal testing would address my hypothesis. As it turns out, my family has rather long generation times and the ancestor in question was my 4th great grandmother (b.1779), bringing the ideal percentage to ~1.56. But I suspect that recombination, in my case, has not favored retention of that line. Since DNA recombination is not random, i.e. some parts of chromosomes recombine frequently, others not at all, certain traits remain linked through generations. While I have no obvious phenotypic traits of my maternal ancestry, my older brother has many and may be a more suitable candidate for testing. Does this seem reasonable?

Thank you,

Shirl

You’re very fortunate in having those long-tailed generations, so the higher percentage sure gives you a better chance to detect the ancestry. As for who to test, you undoubtedly know, since you have training in biology, that phenotype and genotype can often mismatch, so I would test both yourself and your brother. While his phenotype may be more suggestive, your genotype may show evidence as well. When it comes to autosomal testing, it’s so inexpensive these days ($less than $100 a person) that the standard recommendation is to test everyone you can afford to test.

The 1.56% can be a bit misleading. You should inherit around that amount from a 4th gr grandparent BUT your gr grandmother in question was already admixed enough to have been able to PASS for white so the amount of African Dna she possessed was likely under 25% of her total dna. So the MOST of that amount she would have passed to you would be around .39%.

I agree that the total amount is likely to be lower than 1.56%, but again caution that every one of these cases involves a range — these percentages are not cast in stone but range enormously.

Thanks. The breakdowns of average percentages inherited on a generation-by generation basis was very clear and helpful.