Enough with the hype

You knew it was coming.

You knew it was inevitable.

You knew that sooner or later somebody was going to come up with the idea of adding that little button somewhere in the vicinity of AncestryDNA’s ethnicity estimates.

The little button that reads “Share.”

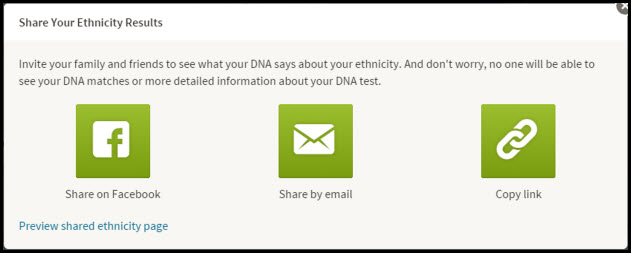

If The Legal Genealogist were to hit that button, right now, up will come this set of options:

And that lets you, if you choose to, share your ethnicity estimates on Facebook, or by email, or by copying and pasting the link provided anywhere you want.

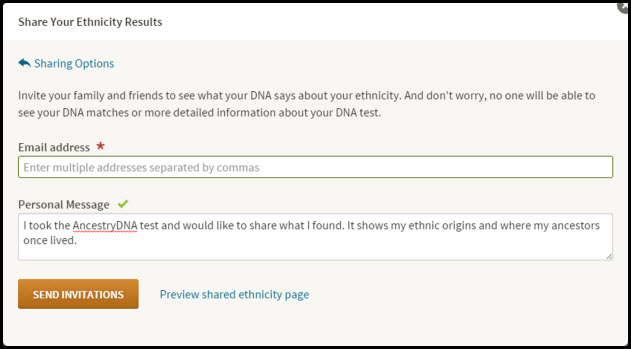

If you select the email option, you’ll get this pop-up on your screen:

All you need to do is enter whatever email addresses you’d like in the line for Email address and hit the Send Invitations button. It will send out an email to all those whose email you’ve entered giving them a link to click to go to your results page.

If you select the Facebook option, and you’re logged in to your Facebook account, it’ll populate a Facebook post for you like the one you see here to the left. All you need to do is add your own comment to go along with it and hit the Post to Facebook button.

If you select the Facebook option, and you’re logged in to your Facebook account, it’ll populate a Facebook post for you like the one you see here to the left. All you need to do is add your own comment to go along with it and hit the Post to Facebook button.

Now, don’t get me wrong, please:

There is absolutely nothing wrong with sharing your ethnicity estimates anywhere you want to.

It’s an interesting tidbit of information and, frankly, the singular reason why some people do DNA testing. They want to see those percentages. Even the idea of getting these percentages is what helps us convince some cousins to go ahead and do the DNA tests we’d really like them to do.

Where the line needs to be drawn is on the hype that goes along with those estimates.

Because there is one word you don’t see anywhere here. Not in the page that gives you your options. Not in the post that goes on Facebook. Not in the message that goes along with the invitation if you choose the send-by-email option. Not in the copy-and-paste code, either.

It’s the word “estimate.”

When you click on the Share button, it tells you that you’re about to “Invite your family and friends to see what your DNA says about your ethnicity.”

If you post via Facebook, it tells your family and friends that what they’re seeing are your “Ethnicity Results” and, it adds, “AncestryDNA helps people discover their unique heritage.”

And if you accept the default version of the email message AncestryDNA sends out when you opt for the send-by-email version, the email will say “I took the AncestryDNA test and would like to share what I found. It shows my ethnic origins and where my ancestors once lived.”

Oh, please.

No.

No, it doesn’t.

Well, okay, it might show those origins and where your ancestors lived, if you happen to be one of the lucky people whose genetic origins are not all jumbled up from generations of mixing English and Irish and German and French. If all of your ancestors on both your mother’s side and your father’s side came from the same place generation after generation, century after century. If there’s no room for doubt based on what reference population your results are compared to or the statistical algorithm chosen for the comparison.

For the rest of us, however, these are not “results” that show origins and residence locations. They are estimates only, and estimates with some serious limitations.

Let me repeat, once more, that we have to keep in mind what these admixture tests do: they take the DNA of living people — us, the test takers — and they compare it to the DNA of other living people — people whose parents and grandparents and, sometimes, even great grandparents all come from one geographic area. Then they try to extrapolate backwards into time. Nobody is out there running around, digging up 500- or 1,000-year-old bones, extracting DNA for us to compare our own DNA to.

So coming up with these percentages in these tests requires this fundamental assumption: that the DNA of the reference populations — those groups whose parents, grandparents, great grandparents and more all come from the same area — is likely to reflect what we might see if we could test the DNA of people who lived in that area hundreds and thousands of years ago.

In other words, these percentages are:

• estimates,

• estimates based on comparisons not to actual historical populations but rather to small groups of people living today, and

• estimates based purely on the statistical odds that those small groups tell us something meaningful about past populations.

The key word here: estimates.

The key word you don’t see, anywhere, in this new sharing feature.

I suppose from an advertising perspective “what your DNA says about your ethnicity” works better than “what our algorithm estimates your DNA says about your ethnicity based on the reference populations we have.” And it’s easier to sell the idea that a DNA test “shows my ethnic origins and where my ancestors once lived” than that it “suggests possible components of my ethnic origins and where a small subset of my genetic ancestors may lived or at least passed through for a time.”

But the reality is that we’re much better off sharing with our families and our friends what DNA testing really can do, and do very well and very accurately: help us find cousins to collaborate with, share research with, document our family histories with.

Enough with the hype.

“Nobody is out there running around, digging up 500- or 1,000-year-old bones, extracting DNA for us to compare our own DNA to.”

Well, you’re 100% correct when it comes to the ethnicity estimates provided by the Big 3 testing companies.

But it may be of some interest that one *can* compare one’s own DNA to that of about 50 different ancient humans who lived between 1000 and 12000 years ago in Europe, Asia, and the Americas, by uploading one’s DNA test results to GEDmatch. I appear to share a 6+ cM segment with an individual who lived in Hungary more than 7000 years ago. Unfortunately, that’s not long enough to have great confidence in a relationship, but it’s certainly the case that other individuals who upload their tests to GEDmatch may have luck in finding much longer and therefore more credible shared segments.

Nevertheless, I do find myself, in responding to DNA questions/statements about ethnicity, repeating the word “estimate” as often as I can. So thanks for making another effort to get that word out into the shared consciousness of the genealogical community.

You’re absolutely right that people who upload to GedMatch can do some of that comparing-to-ancient-DNA, Drew. (Not me, of course, I don’t even get a match at 5 cM. The best I get is 4cM, well below the threshold for meaningful IBD comparison.)

And our friend and colleague Blaine Bettinger believes that even the commercial companies will eventually improve their ethnicity calculations by incorporating ancient DNA into their algorithms.

But for now… realistically… we all need to scream estimates at the top of our lungs, if only to begin to counterbalance the hype.

Judy, Judy, Judy! You are right on point, it is all estimates. To me it is another tool in the tool box and we should never leave or forget the point of conducting research! This is not a way to stop researching. It is a fabulous tool that is helping a lot of folks with mixed heritage. Thanks for the article! Now I need to share it.

It is a tool, Shelley — and one that can be useful. But we have so many people who see their estimates, know they don’t match the paper trail — and then feel cheated. If they understood the limits of these estimates, they wouldn’t feel that way.

Hi All

I agree the word estimate must be out there and understood. I am obviously one of the lucky ones as my estimate is spot on with my tree even down to the Scandinavian as I have been told by a Geneticist that I have Viking DNA because I have Dupuytren’s contracture. It is just a tool and I am working with that with the view that my German which were my Grandmothers parents may have come from further east. It gives me a bit of direction.

Except, of course, that it isn’t a Viking disease: According to the International Dupuytren Society, “While there seems to be a link to people with Northern heritage the theory that Dupuytren’s contracture is a Viking or Celtic disease is probably wrong … The earliest reported case of Dupuytren’s disease is an Egyptian mummy dating back 3000 years.” See here.

Thank you Judy for your usual healthy dose of common sense. I get very frustrated when people take these estimates too seriously and try and make the percentages fit their genealogies. These reports are no better for people like me who do have all their ancestry from the same place. All my ancestry is from the British Isles as far back as I can trace it, but I find it amusing that lots of Americans come out with much higher percentages of “British” DNA than me. In case it’s of interest to anyone I did a comparison of my results from all three testing companies:

http://cruwys.blogspot.co.uk/2015/05/comparing-admixture-results-from.html

I think this is a lost cause, Debbie — people are going to believe what they want to believe — but calling the companies on the hype is all we can do.

This is the same thinking that produces all of those delightful, but entirely incorrect “immediate” family trees that all researchers have to deal with in determining their “real” family tree!!

Sigh… I know… I know…

A real family tree comes from documents alone. Nowhere else.

I disagree. A real family tree comes from evidence — and evidence takes many forms. DNA results can be evidence. A tombstone can be evidence. Oral tradition can be evidence. It’s not just the documents.

I agree about “estimates.” On AncestryDNA it shows that I am 33% Scandinavian, but on FTDNA I am 10%, and on 23andMe I am a mere 2%. So far I have only found one ancestor with a Scandinavian name and he lived in Germany in the 1700’s. So much for estimates. Jim

I have exactly the same issue, Jim: my father was born in Germany and I can trace my German ancestry back 300 years on one side and 500 on the other — but AncestryDNA finds essentially no German and 31% Scandinavian. Right.

Ditto. All my known ancestors are from the British Isles going back 300-400 years (except the indiginous branch and possibly a few Africans- none of which shows up in our DNA, bred out apparently). But my (and other relatives) estimated ethnicity shows a sizable percentage of Scandinavian. We just attribute it to those pesky itinerant Vikings a few centuries earlier, which is about as good an explanation as any. We do have some Scandinavian from somewhere along the line, as my brother and I both have Dupuytren’s Disease, known colloquially as “Viking hand”.

I don’t think my 31% Scandinavian and NO German can be written off to itinerant Vikings… Especially since neither FTDNA nor 23andMe (nor National Geographic) has any trouble finding my Germans…

The only other thing I would add, and I believe that you inferred this, is that estimates can and do change as the customer base widens to more countries, etc.

As the reference populations change, yes, the ethnicity estimates change. But they remain estimates.

Thanks for the reminder Judy. It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of seeing that circle with the colors in it and looking at those numbers. I was a bit surprised when mine came up 51% Irish and not Scottish. I have traced ancestors on both sides back to Scotland for several generations. My results do show 36% Great Britain, which includes Scotland. I have found a couple of direct line Irish connections. But, not 51% worth. However, I do know that some people fled Ireland and went to Scotland. So, it is excellent to be reminded that these are only estimates. I don’t think I say that word enough, but will do so in the future.

Excellent, Diane: that word has GOT to stay in our descriptions, every single time. These are not results, they are estimates.

“Nobody is out there running around, digging up 500- or 1,000-year-old bones, extracting DNA for us to compare our own DNA to.”

Except for that line, I think you are spot on.

There are quite a few scientists ‘running around, digging up 500- or 1,000-year-old bones’ and attempting to extract DNA from them to compare to both other ancient bones and modern day hominids. Now, how relevant all of that is to determining ethnic qualifications is very much up in the air and personally I have become ambivalent to it all. As best I can determine through my own tests (Big Y, full sequence mtdna and Family Finder) and those of both close and distant cousins the only ethnicities not found in my family are Australian & Polynesian Aborigines . . . and I’m thinking of playing matchmaker with some of the younglings so as to collect the full set. 😉

I think it is as much or more important to remind people that all of the collective DNA tests taken worldwide prove that there is only one race, and that is Human. Etnicity is only a unimportant sub-grouping which can make for table talk for geeks.

Okay, so we can amend it to “AncestryDNA and other commercial companies aren’t comparing our DNA to those old bones…” But I agree with the rest of your points: our similarities are oh so much more important than our differences.

You won’t find any Australian Aborigine ethnicity on any of the testers because they don’t have a suitable reference sample for autosomal. The best advice from the four testing companies (including Geno 2.0)was a suggestion to compare with Polynesian, but this is a poor proxy. Recent academic papers show commonality with New Guinea samples – but testing companies either don’t know about this or don’t have reference samples from there either. (Historically, researchers from immigrant populations have often abused the trust of first peoples, so there is some reluctance to provide samples. With recent efforts to restore sacred materials to their original owners, hopefully trust is on the way to being rebuilt.)

Thank you, Judy, for repeating this again. I hope that every time you bring up this point it gets through to at least one person.

My Ancestry DNA results say that I am 12% Irish and less than 1% English, although the paper trail shows about 25% solid English, with some lines going back to Cornwall, and not one drop of Irish. I still suspect that this supposed Irish comes from transplanted English or Welsh, but until if and when I find a viable connection, it’s nothing more than “cocktail party conversation” (though I still prefer to call it “smoke and mirrors”).

I like Tony Burroughs’ take on this. He points out that none of the autosomal information these companies sell to us is scientifically validated. If I remember correctly, their own fine print says it’s for entertainment purposes.

It’s only the ethnicity estimates that lack the degree of scientific validation we might like, Janice. I have no issue with the matching algorithms, at least to the extent that the science is known.

And then there is the issue of recombination. You may not have gotten any (or as much) DNA from that French, Irish or whatever ancestor. My full brother and I do not share the same ethnicity estimate at Ancestry. Our paper trail is pretty clear cut. 25% Irish, 25% Acadian, 50% Great Britain. Ancestry estimates I am 41% Irish, 33% Europe West and only 15% Great Britain. Brother is 27% Irish, 23% Iberian Peninsula and 20% Great Britain. It’s important to click through those estimate graphs and look at the ranges. They are pretty broad.

What I realized from doing this test is frankly my DNA has REALLY traveled the world. It doesn’t mean that I am one specific group but that my ancestry spans the globe, its kind of cool to think of all time and space I ended up here. I could be anywhere but I am not because of my ancestry.

Our footloose ancestors have a lot to answer for — both good and bad!

It might be an interesting tool for some, but for those of us who need more proof than an “estimate” it really loses its interest for me. Being one who had half my family tree wrong, be careful out there. I was lucky, a couple of genealogists seen my posts and told me where I went wrong. If I could have used this tool back then, I probably would have been claiming Henry VIII as my 8th great grandfather.

As long as people understand its limits, it can be useful, Stan, but the problem is that so many people don’t understand the limits and are being misled (or allowing themselves to be misled because of what they want to be true).

This is a concern of mine, too. I am very unhappy with Ancestry’s latest commercial where a customer, who thought he had German ancestry, turns in his lederhosen for a kilt after “discovering” his ethnicity was Scandinavian. READ ANCESTRY’S WHITE PAPER ON IDENTIFYING GERMAN DNA! By their own admission German DNA only has a “recall” rate of 7%. Most of the time it cannot be identified and cannot be differentiated from French DNA. Given the history of these populations, it shouldn’t really be a surprise.

Yesterday I was “manning” a table at our library and a woman wanted to know why she and her identical twin sister got different ethnicity estimates. Got me. Has anyone else encountered this?

Kathy, if you looked at the ethnicity results for my full brother and me you would never assume we are full siblings. I have some Finnish, he has none. He has some Middle Eastern, I have none. Our Scandinavian results vary for me at 42% and him 60%.

Thanks Judy for always saying it like it is.

Thanks for the kind words, Karin!

Thanks to Judy, I now know the white paper that I identified as coming from ancestry, actually came from 23andme. Sorry for the mix up.

Had to share this. 🙂

Thanks again, Judy!

Kathy Reed,

I would like to be able to document that example of the identical twins but I don’t suppose that is possible. That would be very interesting. Most people do not realize that fraternal twins share no more atDNA than other siblings. Identical twins are a different matter.

You have inspired me to try to track down a couple sets of identical twins to see what ESTIMATES each of the members of the sets were given.

And it’d sure be nice to see what you find, Dave!

The first set I was able to track down last night blew my mind. I’m looking for other sets. If anyone has access to the ethnicity PREDICTIONS for a set of identical twins, please contact me: infodoc [AT] DDowell [dot] com

I’ll just note that identical twins having different ethnicity estimates isn’t surprising (as long as the estimates are reasonably similar). For example, at AncestryDNA, the first step in the ethnicity estimate calculation is to randomly chop up the DNA sequence into smaller pieces a total of 40 different times. Each of the 40 chopped up DNA sequences are then analyzed independently, and the range and average forms the ethnicity estimate. Just like those 40 different analyses are not identical due to how/where the DNA is chopped up, the ethnicity analysis of the DNA of identical twins won’t be the same either.

Indeed, identical twins is like doing the analysis 80 times, except in two different batches and are individually averaged to produce an ethnicity estimate.

Of course this highlights the fact that ethnicity estimates are extremely problematic, but it is a scientific explanation of why the results for identical twins can differ.

>> Of course this highlights the fact that ethnicity estimates are extremely problematic

Indulging in understatement, are we? 🙂

The estimate is for those same people who think they can put in their name, parent’s name and maybe a grandparent and get a family tree. Instant gratification with very little effort. Ancestry seems to be branching out in all directions becoming a jack of all trades and master of none.

I don’t mind the people who want it to be that easy. Heck, I wish it were that easy! But telling people it really is that easy does them such a disservice.

I don’t remember where I got your quote (and I am paraphrasing) that the ethnicity estimates are “good cocktail party talk,” but I use that line a lot. I definitely take the ethnicity information with a grain of salt – I can trace my maternal side back to a specific village outside of Hamburg (I am most definitely related to almost all of the current 1500 inhabitants), but do you think that my FamilyTreeDNA map touches Germany? Of course not!

Thank you so much for the logic and common sense!

Right here is where I first said it, Lisa. Wish more folks would listen…

According to FTDNA’s FamilyFinder autosomal test, my DNA is 100% European, which is odd as my mtDNA haplogroup is J (Bryan Sykes’s “Jasmine”) which originated in the Middle East. I suppose it depends on how far back they go in their testing. I understand that my mtDNA J1c2 clade originated in Europe.

FamilyFinder makes me 63% British Isles, 32% West and Central Europe and 5% Finland and Northern Siberia. I was born in eastern Scotland with nothing but Scottish ancestors (including Ulster Presbyterians) and one English line from Northumberland (practically Scottish!). My Y DNA is R1b1a2a1a1b4 and may be “Pictish” if you believe it’s possible to establish that.

A friend who is a genetic genealogist says my 32% West and Central European is probably my Anglo-Saxon component, which most Brits probably have in their DNA. As for the intriguing 5% Finland and Northern Siberia, this friend has tested Cunningham males from my paternal grandmother’s extended family and against expectation they turned out to be R1a. That looks like “Viking” descent, but in fact on DNA databases they have more matches with east Europeans than with Scandinavians. My friend tells me that the R1a people came into Scandinavia and eastern Europe from the far north.

Harry