That Indiana writ

In 1838, at the end of its 22nd session, the Indiana Legislature authorized and published the Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana.

Published by Douglass & Noel, Printers, in Indianapolis, the laws were arranged, compiled, and published by authority of the General Assembly.1

Published by Douglass & Noel, Printers, in Indianapolis, the laws were arranged, compiled, and published by authority of the General Assembly.1

And the very first law in this very early set of statutes is one that has even The Legal Genealogist shaking her head.

Despite the fact that I love law books — and love to poke around in them before heading off to an area to speak, the way I’ll be speaking Saturday, the 24th of October, at the Indiana State Library’s Genealogy & Local History Fair — the fact is, this statute stopped me in my tracks.

Now remember, first, that revised statutes were usually compiled codes. That means that, instead of just passing laws in chronological order session after session year after year, the laws are organized in some fashion. These are generally called codifications, andCodification, by definition, is the “process of collecting and arranging the laws of a country or state into a code, i.e., into a complete system of positive law, scientifically ordered, and promulgated by legislative authority.”2

And the “scientific order” chosen by the Indiana Legislature in 1838 was mostly alphabetical. Gaming, Unlawful, before Gambling, Professional, for example.3

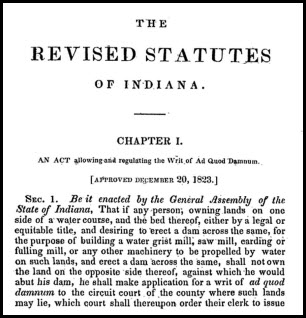

And the first statute included on that mostly alphabetical basis was an act approved 20 December 1823: “An Act allowing and regulating the Writ of Ad Quod Damnum.”4

R-i-i-i-i-g-h-t.

I mean, really. We all run into the Writ of Ad Quod Damnum every day, don’t we?

Well, actually… we do. We just may not realize that’s what it is when we see it.

That’s not really our fault. The law dictionaries are not a whole lot of help on this one. Black’s defines this as the “name of a writ formerly issuing from the English chancery, commanding the sheriff to make inquiry ‘to what damage’ a specified act, if done, will tend. Ad quod damnum is a writ which ought to be sued before the king grants certain liberties, as a fair, market, or such like, which may be prejudicial to others, and thereby it should be inquired whether it will be a prejudice to grant them, and to whom it will be prejudicial, and what prejudice will come thereby. There is also another writ of ad quod damnum, if any one will turn a common highway and lay out another way as beneficial.”5

Not particularly helpful, is it?

And Bouvier isn’t much better: “The name of a writ issuing out of and returnable into chancery, directed to the sheriff, commanding him to inquire by a jury what damage it will be to the king, or any other, to grant a liberty, fair, market, highway, or the like.”6

But when we look at a modern, plain-English dictionary, things start to fall into place: “a writ issued in proceedings (as of condemnation) to assess damages for land seized for public use.”7

Here’s the deal: one of the primary functions of early governments was to develop natural resources and make sure people were fed. They needed things like grist mills and saw mills and things of that nature that had to be propelled by water. But if somebody was going to dam up a water course to harness the power of the water, chances were pretty good that somebody else was going to suffer some damage.

Sometimes the guy who needed the water didn’t own the land on the other side of the stream where part of the dam would have to be built. Sometimes somebody else would be flooded by the overflowing water. And, sometimes, there were already enough mills and dams around so that the proposed use wouldn’t be a good one — of public utility in the language of the law — at all.

And figuring out how much land could be taken, how much a landowner should be paid for the damage, and whether the use should be allowed at all required something a lot more formal than just two people sitting down together to try to settle things. Especially if it really was something the community needed, and the adjoining landowners didn’t want it anyway.

The NIMBY principle — Not In My Back Yard — isn’t something new.

That formal procedure is what the Writ of Ad Quod Damnum was all about. It was a system for the person who wanted to use the water power to force the neighboring landowners to let him do so, if it was in the public interest, and if he compensated those neighbors.

In Indiana, the law required an application to the county circuit court, then the sheriff had to call a panel of 12 jurors to meet on the land and decide impartially, and to the best of their skill and judgment, whether any house would be flooded, whether passage of fish or navigation would be obstructed, and even whether “the health of the neighbors will be annoyed by the stagnation of the waters.”8

The rules were clear:

If on such inquest or other evidence, it shall appear to the court that the mansion house of any proprietor, curtilage, or garden thereunto immediately belonging, will be overflowed, or the health of the neighborhood annoyed, they shall not give leave to build such mill and dam; but if none of those injuries are likely to accrue, they are then to proceed to adjudge whether all circumstances weighed, it be reasonable, that such leave be given, or not given accordingly.9

If permission was given, the applicant had to begin building the dam or mill within a year and finish it within three years. Then he had to “keep it in good repair for public use.”10

You’ll see this sort of thing quite often in court records, when a county court or board of commissioners was authorizing someone to build a dam or a mill. A jury will be chosen to choose the land to be used — and to fix the value of the land taken. The order book may not use the words, but that’s what it is: ad quod damnum.

And that damned writ saved a lot of damned trouble, to be sure.

SOURCES

- The Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana (Indianapolis : Douglass & Noel, Printers, 1838); digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 20 Oct 2015). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 216, “codification.” ↩

- The Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana, at 324-325. ↩

- Ibid., at 59. ↩

- Black, A Dictionary of Law, 33, “ad quod damnum.” ↩

- John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America and of the Several States of the American Union, rev. 6th ed. (Philadelphia: Childs & Peterson, 1856), 68. ↩

- Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (http://www.m-w.com : accessed 20 Oct 2015), “ad quod damnum.” ↩

- The Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana, at 59-60. ↩

- Ibid. at 60. ↩

- Ibid. at 60-61. ↩

Kentucky’s laws are the same. They just added damage to the orchards and mansions. I chuckle over the latter. I published an extensive book on the water grist mills & specialty mills of the area where I live and was actually able to find a lot of the ad quod damnuns (and how they did spell that!). It is a fascinating study when one realizes how important the mills were to the early citizens.

Interesting to see the origins of what is often called the Public Service Board now, as it is in my state. Pretty much the same thing, only now the concerns are often power plants, transmission towers, windmills, and pipelines. I like very much your descripton about how such a board (or jury) should function in the public interest. And, I imagine much like our ancestors, we get worried that somebody with a bit more power or money or influence will overtake their less well-endowed neighbors. I say this after having responded to several alerts from groups concerned about modern versions of the dam and how they might impact our community. Wrote a couple letters of support, and one of hesitant disagreement. Wish I had the answers. I’m afraid our PSB is one that has lost a good sense of what “public good” means.

In colonial Virginia, as the Legal Genealogist no doubt knows, ad quod damnum was also a legal means of docking an entail (or enforcing one), as a suit of ejectment, and f run into one of them, you might be in for a wild ride. First, some great genealogy can come out of this by virtue of who inherited what land and how, but some of the parties are fictitious. And it could possibly end up quite badly for everyone except the legal heir at law. Just sayin…at least in Virginia is could quite well mean a lot more than the taking of a trifling half acre for a mill site.

Colonial North Carolina was the same: the ad quod damnum process was specifically authorized for small entailed parcels (though it may well have been used for more wealthy landowners as well). Remember, of course, that entails were disallowed by law as of the Revolution. And that ejectment was a very different beastie, altogether.

Well and yes and no. But that’s another paper.