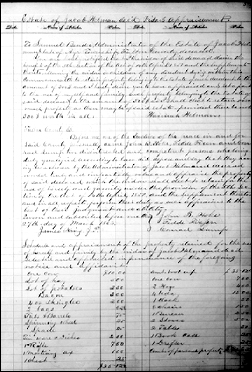

The widow’s appraisal

One cow worth $10.00.

Three dollars worth of bacon.

A spinning wheel valued at 25 cents.

A spinning wheel valued at 25 cents.

A rifle worth $7.50.

A chest valued at 25 cents.

Four beds worth $15.00.

A clock valued at 50 cents.

Eight chairs and two tables and one bureau and one book case and one dresser.

And “a Tract or parcel of land containing about ten acres more or less … together with the buildings and appurtenances valued at $200.”

The residue of the life of Jacob Helman of Ayr Township, County of Fulton and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, on the 27th of March 1853.1

And we know about this because Jacob’s widow Hannah filed a request with the Orphans’ Court of Fulton County:

To Samuel Bender, Administrator of the Estate of Jacob Helmund late of Ayr Township, Fulton County, deceased.

You are hereby notified that I the widow of said deceased claim the benefit of the 5th Section of the Act of 14th April 1851 and the Supplements thereto, allowing the widow or children of any decedent dying within the Commonwealth to retain property belonging to the Estate of such decedent, to the amount of 300.$ and I hereby desire you to have appraised and set off to the use of myself and family, such property belonging to the Estate of said deceased to the amount of 300$ as I shall elect to retain or so much property as then may be of said Estate, provided there be not 300$ worth in all.2

Oh, that makes it perfectly clear, doesn’t it? Hey, The Legal Genealogist is sure that everybody knows “the 5th Section of the Act of 14th April 1851”…

No?

Really?

Okay.

The general theory of the law was that everything a deceased person had at the time of his death ought to be converted into cash and his debts paid before anything else was done. That’s why you see all those estate inventories and the sale amounts assigned to them in probate case files.

But it was pretty clear that selling everything off for the benefit of creditors would have a pretty devastating effect on the families left behind.

So the law stepped in and provided that not everything had to be sold off. First, under an 1846 statute, the widow was allowed to keep for herself and her family anything that somebody who was insolvent would have been allowed to keep (“property … allowed and exempted from levy and sale, under the existing insolvent laws of this commonwealth…”).3

And then came the Act of 14 April 1851 and its fifth section:

That hereafter, the widow or the children of any decedent dying within this commonwealth, testate or intestate, may retain either real or personal property belonging to said estate to the value of three hundred dollars, and the same shall not be sold, but suffered to remain for the use of the widow and children of family, and it shall be the duty of the executor or administrator of such decedent to have the said property appraised …4

In other words, over and above anything else the widow and kids were entitled to under the law, they got to pick out $300 worth of property — either personal property like the cow and the beds — or real property (meaning land5 — and keep it, free and clear of the creditors, up front, before anything else.

These elections tell us a lot about the families affected. Sometimes we might pick up clues about family size — how many beds were chosen tells us a bit about how many people might be sleeping in them, for example.

Sometimes we learn whether this was a farm family or a craftsman’s family — choosing farm implements rather than blacksmith’s tools, for example.

Sometimes we learn that there wasn’t enough property owned by the deceased even to amount to $300.

And sometimes we can pick up clues that aren’t obvious at all.

As in the case of Hannah Helman.

Because, the documents go on to say, Hannah didn’t get the $200 in land she originally asked for in the appraisement book. Beneath the appraisal is this note, dated 18 November 1863:

To Samuel Bender, Admr, of Jacob Helmund dec’d

In consideration of the violent opposition made by certain of the children of Jacob Helmand dec’d, to my being allowed to retain the land above described and appraised I hereby withdraw my claim to have the Same set apart to me and claim the balance of 300$ over and above the amount of the valuation of the personal above described and appraised out of any moneys or effects belonging to the Estate of said deceased which may come into your hands.6

And what does that tell us?

Sure looks to me, when you combine it with a few other things, that you’re getting the story of a second wife feuding with the children of the first, no?

In 1840, Jacob was in the census there in the part of Bedford County that later became Fulton County as a man in his 40s, with a woman in her 40s, and six children ranging in age from five to 19.7

But in 1850, Jacob was shown in the census as age 51, with Hannah more than 20 years his junior and only two Helman children, ages one and four.8 By 1860, there were six Helman children — all age 12 or under.9

Not likely to be one of those little kids with “violent opposition” to their mother keeping the land, is it?

But one of those kids from 1840? Oh yeah…

Yep. Stories to be found everywhere… if we take the time to look.

SOURCES

- Fulton County, Pennsylvania, Widows’ Appraisements Book 1: 3-4, Estate of Jacob Helman (1853); digital images, “Widows’ appraisements, 1863-1963,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 7 June 2016). ↩

- Ibid., Fulton Co., Pa., Widows’ Appraisements Book 1: 3. ↩

- §IX, Chapter 689, Act of 22 April 1846), in James Dunlop, compiler, The General Laws of Pennsylvania … to April 22, 1846 (Philadelphia: T. & J.W. Johnson, 1847), 974; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 June 2016). ↩

- §V, Act of 14 April 1851), in James Dunlop, compiler, The General Laws of Pennsylvania … to May, 1853, 3d ed. (Philadelphia: T. & J.W. Johnson, 1853), 1140; digital images, Google Books (http://books.google.com : accessed 7 June 2016). ↩

- Henry Campbell Black, A Dictionary of Law (St. Paul, Minn. : West, 1891), 997, “real property.” ↩

- Fulton Co., Pa., Widows’ Appraisements Book 1: 4. ↩

- 1840 U.S. census, Bedford County, Pennsylvania, p. 383 (stamped), Jacob Helman; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 June 2016); citing National Archive microfilm publication M704, roll 445. ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Fulton County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, p. 46(B) (stamped), dwelling 158, family 164, Jacob Helman household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 June 2016); citing National Archive microfilm publication M432, roll 783. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Fulton County, Pennsylvania, Ayr Township, population schedule, p. 27(A) (stamped), dwelling/family 1509, Jacob Helman household; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 7 June 2016); citing National Archive microfilm publication M653, roll 1113. ↩

One of my good finds is a complete inventory from my 4x great grandfather’s estate. His 2nd wife died a couple of months after him, so everything was indeed auctioned off -22 pages, down to individual utensils, sacks of pototoes & onions, even a barrel of fermenting sauerkraut. The purchasers are all listed, which in many cases were immediate or distant relatives – or those who woild become so in subsequent years. I particularly enjoy the fact that where thing are misspelled, it’s done with a strong German accent, ie, Mr Hoover became Mr “Hoofer”, which gives you and idea how they spoke. I was particularly impressed with the number of blanket and teapots (presumably used for drawing baths). It’s hard to stay warm in Erie County, New York. I was also interested in what there wasn’t. There were no books, religious items (including Bibles), or guns mentioned there.

Great find, Dave, and great to be using the inventory for more than just face value (asking yourself why no Bible, why no guns is a good thing!!)

good one, it also gives clues to who might be missing as well as who is there.